By Katya Alkhateeb, University of Essex and Faten Ghosn, University of Essex

(The Conversation) – A recent surge in violence against Syria’s Druze religious community has reportedly seen over 100 people killed since the start of May. This is a grim extension of sectarian targeting that began with the massacre of Alawite civilians in March.

Both crises are grounded in the same religious justifications, revealing problems in Syria’s transition following the end of the Assad family’s 53-year rule.

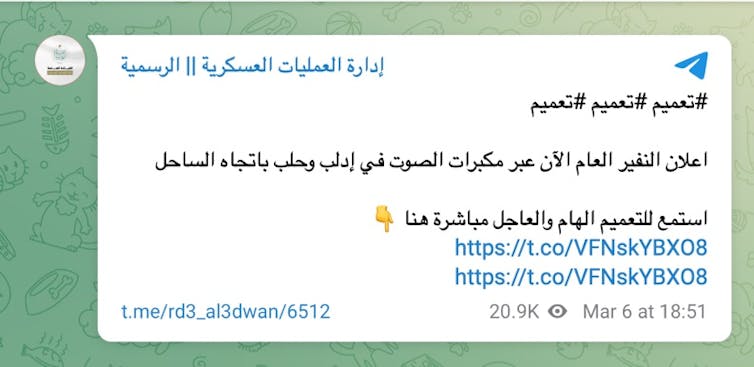

Specifically these atrocities are linked by the misuse of nafir aam – a general call to arms or mass mobilisation. It is an Arabic term rooted in classical Islamic jurisprudence, especially in discussions about jihad and collective defence.

It is declared only when the Muslim community faces an existential threat, such as an invasion or overwhelming danger from an enemy.

Recently though, it has been used by extremist groups such as Islamic State and al-Qaeda to summon Muslims to fight supposed enemies of the faith. These enemies have, in most cases, been innocent civilians.

In March, when gunmen loyal to Syria’s former leader Bashar al-Assad (who is an Alawite) clashed with security forces, the transitional government issued a nafir aam. Loudspeakers in mosques across northern Syria broadcast mobilisation calls, tribal groups pledged support, and recruitment links flooded social media.

The UK-based Syrian Observatory for Human Rights reported that close to 1,400 Alawite civilians were subsequently murdered, with the final death toll likely to be much higher.

Telegram

The same sectarian machinery has now been turned against the Druze. This latest wave of violence was triggered by the unproven allegation that a Druze cleric was responsible for an audio recording containing anti-Islamic remarks. Despite the cleric’s immediate denial, armed groups launched assaults on Druze areas near Syria’s capital, Damascus.

Israel’s prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, vowed to protect the Druze and the Israeli military subsequently carried out a series of airstrikes across Syria. These included strikes near the presidential palace. While Netanyahu has positioned these actions as protecting a vulnerable minority, they risk further destabilising Syria’s fragile transition.

Deeply entrenched sectarianism

Syria’s transitional government is led by the Islamist group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS). Following its campaign against Assad, HTS has been implementing a new policy of tolerance towards minority groups. The Syrian president, Ahmed al-Sharaa, has vowed to protect minorities and pursue more inclusive policies.

But HTS is arguably failing to deliver the inclusive governance it promised when seizing control of the country in December 2024. The seven-member committee for the national dialogue conference, which began in February to discuss a new path for the nation, lacked Alawite, Kurdish and Druze representation.

The resulting constitutional declaration offered no explicit protections for Syria’s religious diversity. It also centralises power in ways that undermine pluralism.

Article 3 of the constitutional declaration states that the “religion of the president of the republic is Islam” and “Islamic jurisprudence is the principal source of legislation”. Officials have clarified that any future parliament would remain subordinate to Islamic law.

The ideological basis and policy for sectarian violence in Syria remains deeply entrenched. A 14th-century fatwa (a religious edict) by Sunni Muslim scholar Ibn Taymiyyah branded Alawites as “infidels”. This fatwa continues to circulate in areas under government control.

At the Brussels donors’ conference on Syria in March, Syrian foreign minister Asaad al-Shibani blamed “54 years of minority rule” for mass displacement and deaths – raising concerns about sectarian narratives. And the integrity of the investigation into the recent massacres have been questioned, notably by the Syrians for Truth and Justice human rights group.

Criticisms have also been made over the inclusion of controversial figures to the newly formed Civil Peace Committee, which is tasked with healing the sectarian wounds left by Assad family rule. One of these figures, Sheikh Anas Ayrout, was reported 12 years ago to have made inciting comments against Alawites.

Civil society organisations, including the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, have called on the government to issue protective religious rulings for minority communities. But their appeals have gone unanswered. And violence, particularly against Alawites in Homs and Aleppo, has surged dramatically.

Photo of Latakia by Maria Turkmani: https://www.pexels.com/photo/woman-and-boy-on-messy-street-14428368/

Five months after Assad’s fall, it seems that Syria is not witnessing the long hoped for fruition of its 2011 revolution, where pro-democracy protests swept through the country, but rather its continuing unravelling.

The groups now in power had little to do with the revolution’s early democratic hopes. They have emerged from transnational jihadist networks with a radically different vision for Syria’s future.

In the view of prominent Syrian intellectual Yassin al-Haj Saleh, Syria urgently needs a period of de-escalation and genuine political concessions. He argues for “taking two or three steps back … to move more firmly forward”. Political solutions must precede the creation of public institutions, not the other way around.

If the cycle of sectarian violence is not broken, Syria risks sliding deeper into communal bloodshed that could permanently fracture the nation’s social fabric.

The international community must act decisively. It has to apply concrete political pressure that makes the protection of all Syrians – regardless of sect – a non-negotiable foundation for Syria’s path forward.![]()

Katya Alkhateeb, Senior Researcher in International Human Rights Law & Humanitarian Law at Essex Law School and Human Rights Centre, University of Essex and Faten Ghosn, Professor, Department of Government, University of Essex and Non-Resident Fellow at Center for Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Arizona, University of Essex

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

© 2026 All Rights Reserved

© 2026 All Rights Reserved