By Stephanie Cleland, Simon Fraser University

(The Conversation) – In recent years, Canadians have been subjected to both severe wildfire smoke and extreme heat events, as evidenced by the record-breaking 2023 wildfire season and the 2021 heat dome. Western Canada in particular has a long history of wildfires and heat waves, and with climate change, communities have experienced an increasing number of days per year affected by wildfire smoke or extreme temperatures.

It’s well understood that exposure to either wildfire smoke or extreme heat poses a significant threat to health. For example, there is substantial evidence linking wildfire smoke to an increased risk of hospitalizations for lung or heart complications, with emerging evidence that exposure may also affect birth outcomes and cognitive function. Similarly, we know that extreme heat can increase the risk of illness or death from conditions related to our lungs, hearts and brains.

However, most available research has focused on the effects of these climate hazards in isolation, without considering what the health risks might be when wildfire smoke and extreme heat happen at the same time. We live in a complex world where we’re rarely exposed to one hazard at a time, and wildfire season overlaps with the warmest months of the year, making it essential to consider the potential risks of concurrent exposure to heat and smoke.

While only a handful of studies have explored the effects of co-occurring wildfire smoke and extreme heat events, early evidence indicates that simultaneous exposure may actually amplify the adverse health effects, leading to worse respiratory, cardiovascular and birth outcomes than either exposure on their own.

This emerging evidence of amplified effects, paired with expected increases in Canadians’ exposure to both wildfire smoke and extreme heat, prompted me and my colleagues at the British Columbia Centre for Disease Control to explore how often, and where, these climate hazards are co-occurring in Canada. In doing so, we aimed to identify priority communities to guide public health communication and adaptation planning in the face of hotter and smokier summers.

When wildfire smoke and extreme heat co-occur

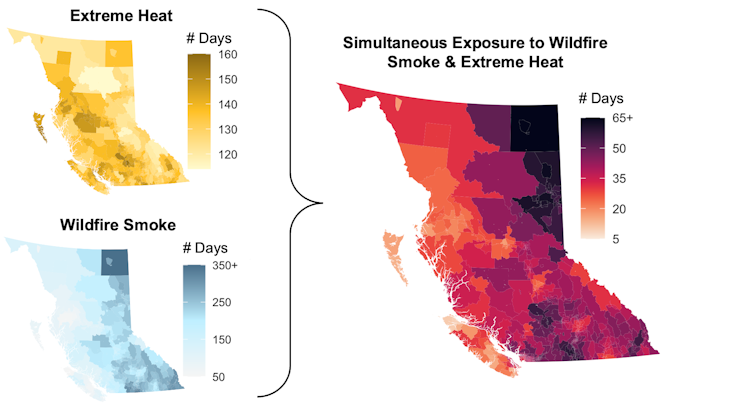

To understand how often communities are simultaneously exposed to wildfire smoke and extreme heat, we analyzed 13 years of temperature and air pollution data across British Columbia. We calculated the number of days affected by both wildfire smoke and extreme heat in each dissemination area (small, government-defined geographic regions that have an average population of 400-700 people). We also assessed if the frequency and intensity of these simultaneous climate hazards has changed over time.

(Cleland et al., 2025), CC BY-NC-ND

We found that wildfire smoke and extreme heat frequently co-occur in British Columbia, with all communities experiencing at least seven, and upwards of 65, days with simultaneous exposure to wildfire smoke and extreme heat between 2010 to 2022.

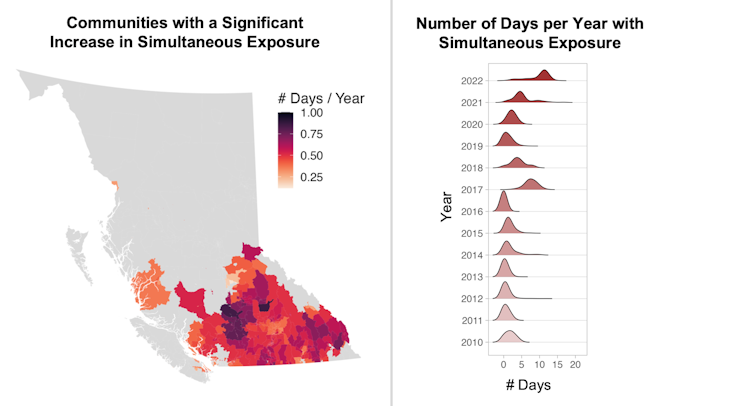

We also identified that the frequency and intensity of these events has escalated over time, with 42.5 per cent of communities (approximately 1.9 million people) experiencing significant increases in their exposure. For example, between 2018 to 2022, communities on average experienced 4.5 days per year with simultaneous exposure to wildfire smoke and extreme heat, compared with only one day per year between 2010 to 2014.

(Cleland et al., 2025), CC BY-NC-ND

We also found that communities across the province were not equally affected by these co-occurring wildfire smoke and extreme heat events. Those in the northeastern and south-central regions of British Columbia tended to experience more frequent and intense exposure.

When we dug a bit more into the characteristics of these highly exposed communities, we found that they were primarily located in rural and remote regions of the province, often with lower socioeconomic status and a higher proportion of susceptible populations, such as older adults.

These types of communities tend to have lower resilience and adaptability to climate hazards, with reduced access to the resources necessary to follow public health guidance and reduce their exposure to wildfire smoke and extreme heat.

Preparing for hotter and smokier summers

Our findings, together with evidence of amplified health risks, make it clear that Canada needs to prepare for hotter and smokier summers. There is also a clear need to increase the resilience and adaptive capacity of rural and remote communities in certain regions of British Columbia.

To do so, we need to invest in strategies that account for the unique ways in which a community experiences wildfire smoke and extreme heat as well as their specific needs and susceptibilities.

While Health Canada and the British Columbia Centre for Disease Control provide guidance on actions to take when exposed to wildfire smoke and extreme heat together, a recent review of public health guidance on simultaneous exposure to smoke and heat found that the current messaging is often incomplete and inconsistent. This unclear messaging can make it difficult for communities to adequately plan and prepare for these recurrent and intense climate hazards.

Photo by Gylfi Gylfason: https://www.pexels.com/photo/stunning-aerial-view-of-icelandic-volcano-eruption-30100616/

Additionally, a lot of the strategies that cities currently rely on to reduce exposure to smoke or heat do not account for the complex world of multiple hazards. For example, cities often open cooling centres during periods of extreme heat to provide access to air conditioning, but these centres don’t always have air filtration.

Similarly, cities often designate cleaner air spaces during periods of wildfire smoke to provide access to clean indoor air, but these spaces don’t always have air conditioning.

Moving forward, Canada needs to invest in co-ordinated public health guidance and adaptation strategies that serve multiple purposes and account for the numerous climate hazards that communities face each year. In doing so, we can better protect the health and well-being of the communities that are experiencing increasingly frequent and intense wildfire smoke and extreme heat events.![]()

Stephanie Cleland, Assistant Professor, Faculty of Health Sciences, Simon Fraser University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

© 2026 All Rights Reserved

© 2026 All Rights Reserved