Ann Arbor (Informed Comment) – Iranian President Massoud Pezeshkian landed himself in hot water on November 6 by broaching the possibility of having to evacuate Iran’s capital, Tehran, if the current water shortage is not alleviated. He said, “If it does not rain in Tehran by December, we should ration water; if it still does not rain, we must empty Tehran.”

BBC Monitoring. reports that hardliners and their media have kept up a barrage of criticism of Pezeshkian for negative thinking. He has also been subject to ridicule on social media, since, people say, there is nowhere to evacuate the capital’s 9.8 million residents.

The boosterism of the hard liners, however, is confronting the reality of climate breakdown, which is already hitting Iran hard and will make some of the country uninhabitable in the coming decades.

The head of the regional water company said on November 6, “Higher than normal heat has intensified the evaporation of water resources and Karaj Dam is currently more than ninety percent empty.” The Karaj Dam serves Alborz Province just northwest of Tehran, the capital.

Or by check:

Juan Cole

P. O. Box 4218,

Ann Arbor, MI 48104-2548

USA

(Remember, make the checks out to “Juan Cole” or they can’t be cashed)

The director of Tehran’s Water and Wastewater Company, Mohsen Ardakani, had said on November 6 that Iran has faced six years in a row where the rains have not come. This year, Tehran Province only received about 6 inches of rainfall. That is desert-level water. You need at least 10 inches a year for rainfall agriculture.

Ardakani said that the five main water supply dams in Tehran province are only 11 percent full, saying: “This is the lowest amount of water storage in history since the Tehran regional dams were constructed, and despite five consecutive years of drought, all efforts are made not to implement water rationing in the capital.”

All across the country, rainfall for the past year is 82% below the long-term average. Iran’s Meteorological Organization said that in the provinces of Yazd, Hamedan, Markazi, Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad, Kermanshah, Kurdistan, Khuzestan, Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari, Ilam and Isfahan, there has been a hundred percent reduction in precipitation in the past year.

Iranian media report that there is no expectation that significant amounts of rain will come during the next two weeks.

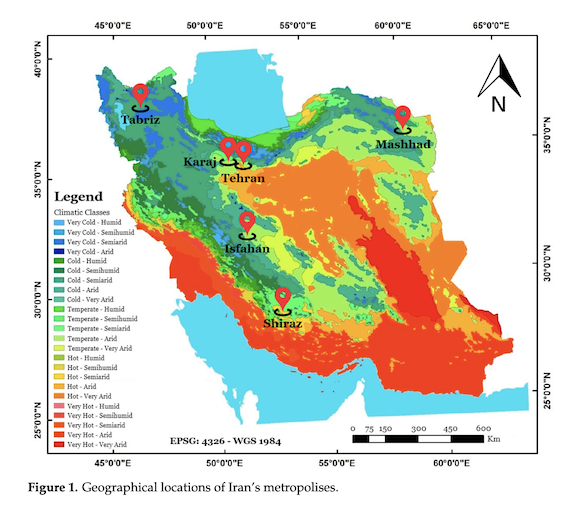

Iran’s Meteorological Organization said that the primary dams that provide drinking water to cities such as Mashhad, Tabriz and Tehran had neared “water day zero,” that is, bone dry. Iran does have a lot of aquifers, but there are dangers in resorting to ground water. One is that it will be used up faster than it is replenished. The other is that pumping up ground water causes subsidence, the sinking of the land.

The major city of Isfahan in center-west Iran has suffered from significant subsidence incidents.

Never miss an issue of Informed Comment: Click here to subscribe to our email newsletter! Social media will pretend to let you subscribe but then use algorithms to suppress the postings and show you their ads instead. And please, if you see an essay you like, paste it into an email and share with friends.

When Iran’s minister of energy went to Garmsar in Semnan Province in early October farmers staged a rally at the place he was staying to protest shortages of water. They chanted “Enough promises! We need water, not words.”

Fatemeh Chaparinia et al. writing in Scientific Reports last April reviewed climate data from 29 provincial capitals from 1992 to 2022 and found clear warming trends and changes in rainfall patterns. Chaparinia is a professor in the Department of Environmental Health Engineering, School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences.

She and her team found that most of Iran’s cities have gotten perceptibly hotter. Almost all of the 29 urban centers under review experienced increases in their average daily high temperatures, and three quarters showed a significant rise in average daily temperatures, with a rise of 0.16º C. per year.

That’s pretty scary, since it translates into 1.6º C. every ten years. In a thirty-year study that equals a 4.8º C.increase (8.64°F.). In all of the last 250 years the earth’s average surface temperature has heated up 1.3º C. (2.34º F.) because of people burning coal, petroleum and fossil gas, which puts heat-trapping carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Iran, like the Middle East in general, is heating up twice as fast as the global average.

More days now see temperatures exceeding the historical average. More than 70% of these cities experienced a significant increase in the number of unusually hot days.

From Asfari, R., Nazari-Sharabian, M., Hosseini, A., Karakouzian, M. (2024). Projected Climate Change Impacts

on the Number of Dry and Very Heavy Precipitation Days by Century’s End: A Case Study of Iran’s Metropolises.Water, 16 (16), 1-18. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/w16162226. distributed under the terms and

conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Chaparinia and colleagues also found that rainfall patterns have shifted. In the past thirty years there have been fewer heavy rainfall events. “Very wet” rainfall days decreased a lot in 11% of the cities, and “extremely wet” rainfall days went down in 22% of the cities. Obviously, geography helps determine these trends. Rasht, up on the Caspian, which gets lake effect rains, saw an increase in annual rainfall of 19 mm (nearly an inch) per year. Other cities showed a fall in rainfall.

Dry periods are becoming longer in some areas. About 15% of cities witnessed a significant increase in the number of consecutive dry days, with Khorramabad in Lorestan in the southwest increasing the most -— by about 4.4 additional dry days per year.

They conclude that climate breakdown is undoubtedly having an impact on Iran. Temperatures are rising, rainfall is decreasing in many areas, and dry spells are persisting longer. All of these trends spell increasing water scarcity, as we are seeing in Tehran and elsewhere this fall.

© 2026 All Rights Reserved

© 2026 All Rights Reserved