On the other side, Mahmoud Darwish never abandoned his human essence as a poet. He kept echoing the resonance of that poem, which fractures political geography and dissects history on the table of truth. The collective feeling of survival consumed both the poet and the Palestinian man. The poem became the most faithful expression of that survival. It seemed to be the only truth when all truths about historical Palestine were gathered. But what about Israel?

One of the most astonishing and devastating answers lies in Darwish’s 1988 poem, written during the First Intifada:

“O those who pass between fleeting words Carry your names, and be gone Rid our time of your hours, and be gone Steal what you will from the blueness of the sea And the sand of memory Take what pictures you will, so that you understand That which you never will: How a stone from our land builds the ceiling of our sky. … It is time for you to be gone Live wherever you like, but do not live among us It is time for you to be gone Die wherever you like, but do not die among us For we have work to do in our land.”

I imagine the poetic echo in Darwish’s heart reaching his coffee cup, while on the other side, Shamir embodied the truth of what the West itself once called “the scum” it had cast onto Palestinian soil.

The war, then, was not over land or history, but over the spaces between the poem’s lines. The Knesset failed to ban the poem, knowing it was like clouds in Palestine’s real sky—untouchable by any “Iron Dome.” The poem remains Israel’s most painful literary wound, described by both left and right as “a plague” and “a historical bomb that destroys Israel.” That explains its resurgence today, amid Netanyahu’s genocidal war on Gaza.

Years ago, I wrote an article titled “An Israeli Poem in Gaza,” where I revisited Darwish’s poem but focused on another—by Yehuda Amichai. I had no idea Gaza would face such death two years later.

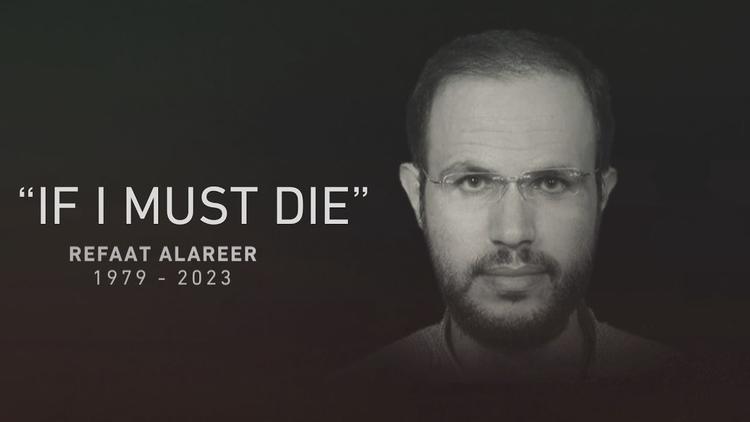

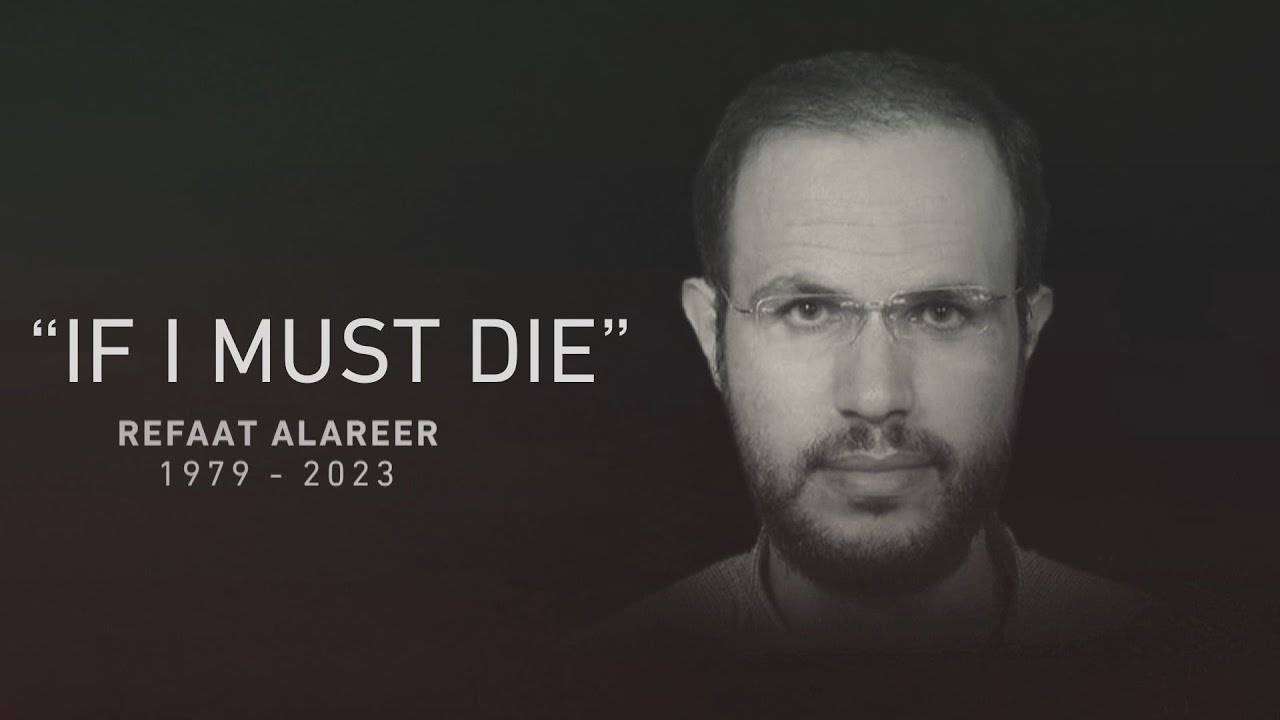

It was a perfect story, set in Gaza. Professor Refaat Alareer, from the Islamic University’s Faculty of Arts, handed his students a poem without naming its author:

“On a roof in the Old City Laundry hanging in the late afternoon sunlight: The white sheet of a woman who is my enemy, The towel of a man who is my enemy, To wipe off the sweat of his brow. In the sky of the Old City A kite. At the other end of the string, A child I can’t see Because of the wall. We have put up many flags, They have put up many flags. To make us think that they’re happy. To make them think that we’re happy.”

The students, all young women, unanimously assumed the poem was by a Palestinian poet from Jerusalem. One said, “No Israeli could write about Jerusalem with such warmth.” But the shock came when Alareer revealed the author: Yehuda Amichai, Israel’s most celebrated poet.

The classroom erupted. The students reeled, revisiting their assumptions. That lesson, held two years before the genocide in Gaza, shattered the stereotype that Gazans only respond to news of Israeli rockets.

Al Jazeera English: “‘If I must die’: Remembering Palestinian Poet Refaat Alareer ”

‘If I must die’: Remembering Palestinian Poet Refaat Alareer

But the deeper tragedy is this: the professor who taught them that poem—Refaat Alareer—was later killed by Israeli missiles. The army that produced Amichai’s poetry also silenced the man who taught it.

After publishing my article, I received an email from Avi Melamed, an “Israeli expert on Middle East affairs,” expressing deep admiration for my piece. He said he shared my interest in Iraqi music, especially the work of Jewish Iraqi composer Saleh Al-Kuwaity—his maternal grandfather had immigrated to Israel from Iraq.

But what would Melamed say now, after seventy thousand Palestinians have been killed in Gaza, half of them children? What cultural empathy remains after such an immoral war? Can he explain what the “most moral army in the world” was thinking when it killed a poetry professor who taught Amichai?

Refaat Alareer taught his students the poetry of Israel’s greatest poet. But the Israeli army killed him anyway. Because it does not understand that poems do not die. What remains is what poets build. And the poem cannot be killed.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Monitor or Informed Comment.

Unless otherwise stated in the article above, this work by Middle East Monitor is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Unless otherwise stated in the article above, this work by Middle East Monitor is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

© 2025 All Rights Reserved

© 2025 All Rights Reserved