( Tomdispatch.com ) – It’s been more than nine months now since my friend, famed cartoonist Jules Feiffer, died, a week before his 96th birthday after continually warning me that the evil spirit that had descended on this country was leaving him frightened and dispirited. He was glad, he told me, that he was old and close to the end in an era he considered more dangerous than the Civil War and more treacherous than the Reconstruction era. He had, he insisted, lost both heart and hope. I found that difficult to take too seriously. After all, hadn’t he survived the Great Depression, World War II, the Cold War, the McCarthy-era Red Scare, the nightmare of Vietnam, and the “Hard Year” of 1968, while being dubbed the greatest political satirist of his time?

And as it happened, he died only a few days after finishing a graphic memoir, “A License to Fail,” which stunned me with its insight and wit. It reminded me of the shock and awe he had evoked 60-odd years earlier with his spindly cartoons in New York’s Village Voice harpooning the hypocrisies of the government of that era, the developing war in Vietnam of that moment, and the self-delusions of his liberal audience, which still prevail.

The difference between Jules’s work then and now, however, was his emotional motivation. Anger had fueled his Vietnam Era cartoons. In the age of Donald Trump, he was, he assured me, “fed up.”

As he told me recently, “Dr. King said the arc of history bends toward the good, but I say the arc is up for grabs and can move in directions we don’t dare think about. Like civil war. Like the American dream becoming the American con job.”

And yet, for all his pessimism, I found Jules at 95 a beacon of hope. Amid the rising negativity and growing passivity of our increasingly endangered world, he never gave up.

To combat his macular degeneration, he taught himself to look around corners as he drew. He could barely walk a block, but somehow, he still managed to do so. His heart, lungs, and kidneys were on speed dial to the ambulance corps and he was all too frequently hospitalized. Yet he just kept coming back.

Jules was anything but modest. He readily agreed with me that he was a national treasure. As I assured him more than once, I considered him my personal reward for getting old and distinctly an inspiration to keep on going. After all, by the time we met and became dear friends, I was almost 80 and he was almost 90. He agreed I was right.

For five years, from 2017 to 2022, Jules and his wife Joan lived in my small Long Island town, Shelter Island. Jules made me breakfast almost every Sunday morning. Always scrambled eggs. He was incredibly precise about it, as much an artist when it came to those eggs as he was when it came to his acclaimed cartoons and book illustrations. He broke our eggs with a quick rap of a knife, whipped them in a bowl, slid them into a pan, and then shoveled my portion onto a plate and cooked his for another 30 seconds. As the apprentice/acolyte, I made the toast. I brought the food to the table. He always insisted on doing the dishes. Then we talked for at least two hours. Actually, Jules did most of the talking and I, most of the listening.

He said things like, “Maybe my old age and fartism need to be factored in here, but to my mind Republican politicians just aren’t American citizens. They don’t care about their constituents or the Constitution. Like the tobacco executives, they feel that killing your kids and grandkids is just the cost of doing business.”

Meeting the Masses

Jules was born in New York City’s the Bronx, a beanpole who said he hated his body and tried to have nothing to do with it. He claimed to have done only two push-ups in his whole life.

“I can’t do anything physical,” he would tell me. “My body’s just along for the ride. It’s there to carry my head and nothing more. Now I find myself in this old man’s body which still has no relation to me. I have no sense of direction. I used to rage at myself. Now, I just start every trip at least a half hour early.”

His proficiency with computers, phones, cars, and the like was virtually nonexistent and he resisted instruction. (“Machines hate me,” he said.) But he still had a remarkable talent for sponging up information and ideas. One Christmas long, long ago, his sister, a Stalinist, gave him a history of cartooning that introduced him to the radical writer Max Eastman’s controversial socialist magazine The Masses.

“It blew a hole in my mind,” Jules told me. “It gave me permission not just to be a boy cartoonist, but to say something. Then the Army radicalized me, focused my rage. I couldn’t hate my family because I thought they had my best interests at heart, but the Army didn’t, not with their lying and ethical abuse. The Army made me an angry satirist.”

He was drafted into the Army in 1951 during the Korean War and ended up doing animation for the Signal Corps. He never went to college and dropped out of art school. Early on, he was filled with pretension and rage and, as he matured, became something of an intellectual bad boy, the only proper response, he came to believe, to an evil, unfair world.

Those hours I spent with Jules sometimes expanded into lunches with a mutual friend, the actor Harris Yulin, who lived in nearby Bridgehampton. A brilliant Shakespearean teacher and director, Harris made his living as a mostly nefarious cop, judge, or government official in blockbuster movies like Scarface and Clear and Present Danger. On stage, he also played President Richard Nixon, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, and Senator Joe McCarthy.

Harris was my age and we both played the straight man for Jules, especially for his remarkable array of Zeligesque, non-fact-checked memories. When Harris, for instance, mentioned acting with Julie Andrews, Jules would promptly recall being at her wedding. When I mentioned reading William Styron, Jules instantly recounted a drunken evening with that well-known novelist on Martha’s Vineyard and then riffed on why novelists, who work alone and inside their heads, tend to be jerks, while playwrights, who work collectively, are mostly fine guys. Of course, Jules was both.

Once, after Harris mentioned a Philip Roth novel he was reading, Jules recalled sitting between Roth and Jackie Onassis at a dinner party. Jackie, he told us, placed a folded paper in Jules’s hand and asked him to pass it to Roth. A few days later, Jules asked Roth what was on the paper.

“Her phone number,” he replied.

“Have you called her yet?” asked Jules.

Roth made a face. “Are you kidding? Who wants photographers outside your house all night?”

When John Belushi’s name came up, Jules recalled meeting him in his building’s elevator as the young comedian was heading to his therapist. Jules introduced himself and invited him to stop by afterward. “Sweet guy, stayed for an hour,” he told us. “He asked me if being famous was a drag for me, too. I told him no, since people knew my name but never recognized the face.”

Frauds and Favorites

He was not shy about his opinions. Norman Mailer, Ernest Hemingway, and Arthur Miller? All of them, he insisted, were overpraised frauds.

Really? Or had they annoyed him one drunken night at that legendary New York hangout Elaine’s, a second home for Jules?

On the other hand, the comedians, Lenny Bruce, Mike Nichols, and Elaine May, whose bold work he felt had empowered him, the ones who had given him permission to dare, couldn’t be praised enough. Nor could humorist Robert Benchley, whose “schmucky WASP characters” led Jules to his own alter ego character, Bernard Mergendeiler, who wasn’t assertive enough either to get his order taken at a restaurant or even get the elevator operator to stop at his floor. Of those who followed Jules, he particularly liked Doonesbury‘s Garry Trudeau and the Daily Show‘s Jon Stewart.

Jules and I regularly talked about politics. He had, he felt, been disappointed all too often. The only time he actually campaigned for a candidate was when the acclaimed journalist Sy Hersh persuaded him that Eugene McCarthy’s election was critical to the fate of the nation. Jules was at a hotel in Chicago for the Democratic Convention of 1968, drinking with radio personality Studs Terkel, when he saw a group of young workers for the presidential campaign of Senator Eugene McCarthy being driven into the hotel’s plate-glass windows by cops who were beating them with their batons. Calls to McCarthy upstairs were fruitless. He refused to come down. Jules quit the campaign.

For all the betrayals he felt he had experienced, he still believed that he had lived a lucky life. Half a century ago, over scotch at the Des Artistes bar in New York City, Irwin Hasen, co-creator of the comic strip Dondi, had characterized it to him this way: “I can’t believe we’re getting away with this!” Jules agreed that it was indeed amazing to get paid for what you had always wanted to do as a kid.

There were, of course, bumps in the road — periods of alcoholism and two unhappy marriages. In the late 1950s, he drew ads for a bank until a reviewer for the New York Times, Herbert Mitgang, gently suggested that he not sell out. He stopped, he told me, and by doing so changed his life. In the end, he would win an Oscar for an animated short film, Munro, about a four-year-old drafted into the Army, a Pulitzer Prize for his cartoons, and two Obies for his off-Broadway plays, Little Murders and The White House Murder Case. That, of course, didn’t stop him from complaining that he had never won an Emmy or a Tony.

Thinking about Jules

At some point on those Shelter Island Sundays we spent together, he would abruptly tell me to go home. Joan would be waking up soon and would need her coffee. In any case, he needed his nap.

Even now, on Sunday afternoons, I imagine Jules heading upstairs, leaving me feeling both abandoned and happily sated with his insights, one-liners, and energizing BS. I think he was the smartest, most complex person I ever knew, someone who could be both heartwarmingly kind and charmingly nasty, often in quick succession.

More than once, he said to me, “The blessing of Covid is I don’t have to go to those fucking parties where I never hear anything anyway from people who don’t have much to say in the first place.”

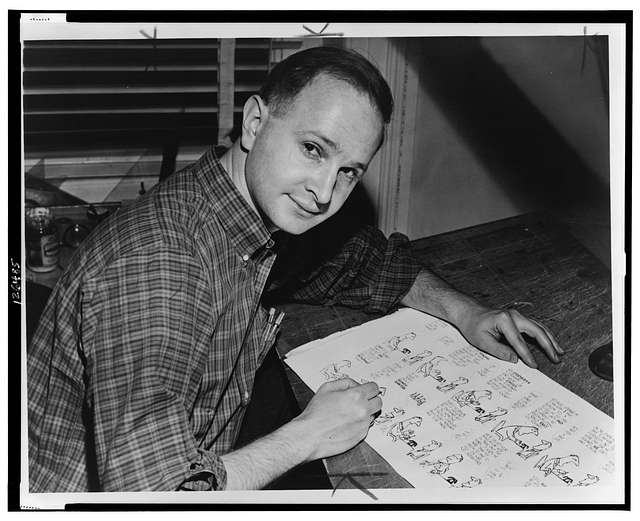

Jules Feiffer, Seated at Work on a Cartooon, Dick DeMarsico, World Telegram and Sun, Library of Congress Collection, Public Domain. Via Picryl

But, of course, he went to those parties. That was the giveaway. The gawky kid from the Bronx loved the acclaim of all those people who still told him how his sixties cartoons in the Village Voice had exposed the hypocrisy of all their friends and neighbors; how the movie he scripted, Carnal Knowledge, prepared us for understanding toxic masculinity and the Me Too movement; how his children’s books brought out the imagination in all ages.

And he worked every day. On the Island, he sat cramped at a tiny table by the door. When he and his wife moved to upstate New York, he sprawled in a splendid studio overlooking a meadow and a lake. From both, in recent years, the results included an acclaimed children’s book, Amazing Grapes, and his as-yet-unpublished graphic memoir that stunned me with its insight and wit, A License to Fail.

That license, which he always insisted to students was critical to success, was the key to the bold surprise in his own work. Get out there, fall on your butt if necessary, but then get up and soldier on. I got to watch some of the failing and successful soldiering on of his last two books, the revising and rewriting, the precision of cracking the eggs of thought and cooking them to perfection. A practically blind, deaf, immobile old man in his nineties, he pumped up my own ambition. Once dismissed on those Sunday afternoons, I headed for my own desk.

I would think about what he had said. I might even dip back into the work of the two journalists who, in the last century, gave him permission to push on, I.F. Stone and Murray Kempton — and the one he admired now, Ta-Nehisi Coates, and wonder, as he did, where we lost our Mr. Smith goes to Washington confidence. Remember when we believed that all you had to do was expose the evil vested interests and they would be defeated?

Time ran out on Jules Feiffer. Sadly enough, he lived deep into but not out of the era of Donald Trump. He didn’t live long enough to see the vested interests he loathed be beaten. I hope we do. Certainly, Jules left us the words and pictures we need to inspire us to beat them. To keep going; fall and get up; fail and, in the end, succeed.

Copyright 2025 Robert Lipsyte

Via Tomdispatch.com

© 2026 All Rights Reserved

© 2026 All Rights Reserved