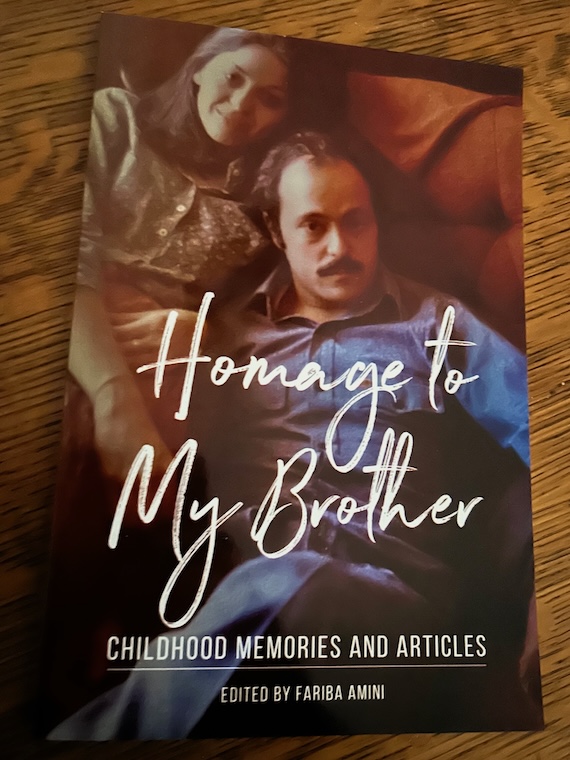

Newark, Del. (Special to Informed Comment; Feature) – My brother Mohammad Amini was a revolutionary and an early leader of the Confederation of Iranian Students, perhaps the largest student movement in the world. He was a Maoist who over time turned into a nationalist.

Our parents were married by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, then a simple cleric, who shared poetry with my father. Then just before the Revolution, my father, Nosratollah Amini, visited Khomeini in Neauphle-le-Château, outside Paris, where he sat under an apple tree.

Khomeini saw all of Iran’s luminaries, my father among them. The whole world was watching this cleric who had spent years in exile in Najaf, in Iraq. From being relatively unknown, he became the face of Iran. He became the Revolution’s voice.

When Khomeini saw my father, the first thing he asked was how is Nahid khanum, my mother, who he remembered very vividly, having known her as a young girl. My parents had met in Khomein, a city some few hundred kilometers from Tehran, where Khomeini was from. Later he became known as Ayatollah Khomeini as the leader of the Iranian Revolution.

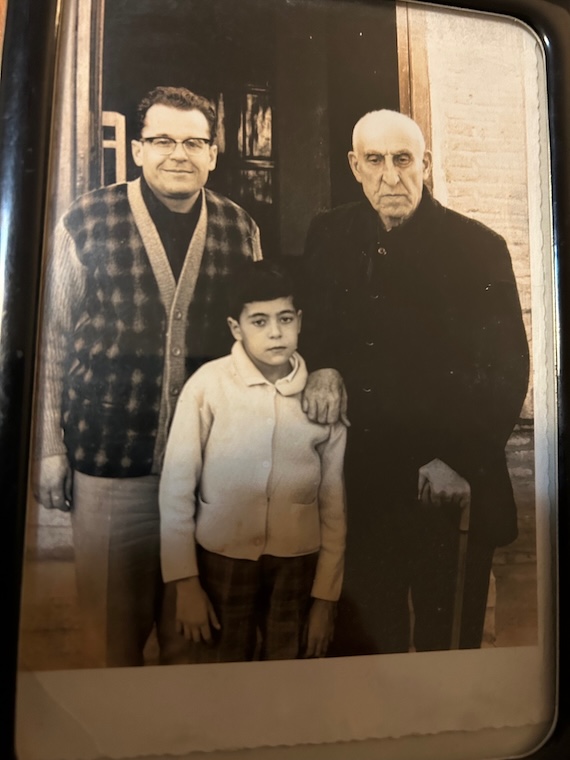

My grandfather was a doctor in the region. Khomeini had visited him many times, but my grandfather did not like to talk politics; Khomeini did. My grandfather had told him that he was not interested in politics.

My brother Mohammad left Iran at the age of seventeen, having graduated from the prestigious Alborz college, a school founded by Samuel Jordan, an American Presbyterian missionary.

He came to Utah where he wanted to study geology. But then he got involved in the student movement. It was the height of the Vietnam war. He abandoned his studies and became a revolutionary.

Mohammad loved Iran. I remember traveling with our parents throughout t Iran, traveling in our old black Mercedes with our chauffeur, Mohammad Agha. We never stayed in a hotel or caravanserai as my father was well known, and we could stay with friends. Mohammad always brought his notebook with him and jotted down everything. He had a keen eye for the villages and their inhabitants. He had had polio, so he was also very weak. As a young child he had visited my father in prison in a wheelchair. This was after the 1953 Coup when all the members of the National Front had been imprisoned. My father Nosratollah had been the the personal lawyer of the nationalist Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh, who was deposed by the CIA coup.

My brother Mohammad became a historian of Iran, but he rarely wrote in English. His love of the Persian language was his forte. Every week he appeared on an Iranian TV channel in California, eloquently holding forth on a variety of topics concerning Iranian history. Like my father, he knew Persian poetry by heart.

He once said of the mandatory veiling (hijab) demanded by the government in the Islamic Republic of Iran, that it was “the most heinous symbol of the regime’s dominance over the most private parts of people’s lives; the fight against it is the central discourse of freedom in Iran.”

Then Covid appeared and he got very sick. Yet he continued his talks, even if at times it was difficult for him.

I went to Irvine too late. He had been transferred from the hospital to his daughter’s house. Fifteen minutes after I arrived at their house, Mohammad died in front my eyes. I think he had tears in his eyes.

Then he left me for good. I spent the last night in his bed that night. My brother left an amazing legacy. To this day, people send me emails and remember him on Facebook. He had an incredible memory, like my father. He saved my life when I was a six-year-old girl with long black hair. It was in Qom, the most religious city in Iran. Mohammad saved my life in Qom……. But I did not save him, in Irvine, California.

- Don’t try to grab this tumbler from my hand;

I’ll dye my sallow cheeks bright ruby red.

Then when I die, use wine to wash my corpse

and weave my final shroud from dried grape vines.

— Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, trans. Juan Cole

© 2026 All Rights Reserved

© 2026 All Rights Reserved