( Tomdispatch.com ) – After a year of gutting the United States government, deploying armed jackboots to American cities, and bombing at least seven countries, the Trump administration kicked off 2026 by invading Venezuela and kidnapping its president, Nicolás Maduro, and his wife, Cilia Flores. In the wake of that assault, President Trump doubled down on his abandonment of the isolationist positions he once supposedly held, threatening military action against Colombia, Cuba, Iran, and Mexico. He then vowed that the U.S. would come to “own” Greenland either “the easy way” or “the hard way.”

In truth, American imperialism defines much of this country’s history, but the latest escalation comes at a time when Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents have also been deployed around the nation to grab immigrants off the streets and whisk them to detention centers. Meanwhile, Trump has continued to preach the jingoistic gospel of stopping the arrival of new refugees and migrants, while blasting European governments over migration — even as he vows to launch military campaigns that will undoubtedly result in further mass displacements and fleeing people crossing borders in search of safety.

Destabilizing countries the world over and then attacking the people who flee those wars is, of course, nothing new. From the September 11th attacks in 2001 until September 2020, this country’s war on terror, according to one study, displaced an estimated 37 million people in eight countries. And that figure doesn’t even include several million displaced during smaller conflicts the U.S. participated in from Chad to Tunisia, Mali to Saudi Arabia. Nor does it include the number of people displaced by Israel’s five wars since 2008 in and around the Gaza Strip, its land theft in the occupied West Bank, or its frequent airstrikes in Lebanon, Syria, and even Iran, all made possible thanks to Washington’s financial and military support.

When it comes to Washington demonizing the people displaced by its weapons, just ask the Palestinians. Millions of them live strewn across the map of the Middle East and beyond thanks to Israel’s ongoing military occupation and the American tax dollars that have enabled it.

“Eight Lives, Gone Just Like That”

In March 2015, I sat in the back of a taxi bound for Saida, a Lebanese coastal city a little less than an hour south of Beirut. The taxi hummed down the highway, the sea blurring through the windows to our right, and then swerved inland. Saida is more than 30 miles north of the country’s boundary with Israel and some 50 miles west of the border with Syria, but even that deep inside Lebanon, a de facto border appeared in the front windshield. The driver made a series of turns, braked, and inched toward a military checkpoint outside Ain al-Hilweh, a Palestinian refugee camp.

Lebanese soldiers appeared on either side of the vehicle. Their job was to decide who could — and could not — enter the camp. After reading over our documents and ensuring that we had the proper military permission to enter the camp, the soldiers motioned the driver to move forward. We eased in amid a sprawl of ramshackle homes, many built atop one another. It was a dusty, humid day, but people clogged the streets. Children punted a soccer ball back and forth in the road. Motorbikes trembled over potholes. Men stood around in knots, smoking cigarettes and sipping coffee, and some walked by with Kalashnikovs slung over their shoulders.

Along with an American photographer and a Lebanese reporter, I had gone to Ain al-Hilweh, the largest of Lebanon’s 12 Palestinian camps, to speak to people who had been doubly displaced by the war in neighboring Syria. As that civil war tore through the country — a war that drew interventions from the U.S., Great Britain, France, Israel, Russia, Iran, and several other places — Palestinian refugees from Syria found themselves fleeing to Lebanon. The population of Ain al-Hilweh alone had swelled by tens of thousands.

Of the Palestinians we met that day, the only ones who had ever set foot in their ancestral homeland were those who had been born before — and lived through — the 1948 war that led to Israel’s creation. What we’d soon learn, however, was that a term like double displacement failed to capture the extent to which borders had governed every aspect of their lives in permanent and repeated exile.

In a corner store with barren shelves, we found Afaf Dashe sitting in a small chair near the counter. At 70 years old, she had survived the Nakba — Arabic for catastrophe, the term Palestinians use to describe the ethnic cleansing of their country since 1948 — as a three-year-old girl when her family fled to Syria. She had grown up in a suburb of Damascus, married, and raised children. When civil war started to rip through Syria in 2011, she and her family gritted it out through four years of barrel bombs, airstrikes, and shelling before they finally escaped.

While Ain al-Hilweh offered some respite, it offered neither true safety nor stability. In Lebanon, decades of state repression, lethal Israeli interventions, and failed Palestinian rebellions had left such refugees particularly vulnerable. Rather than setting down new roots in that dismal camp, Afaf explained, three of her daughters, along with five of her grandchildren, had decided to risk taking the long, often deadly journey to Europe. After crossing from Syria to Lebanon, they parted with Afaf and continued on by sea to Libya. They then paid smugglers to board a boat bound for Italy. As Afaf reached that point in her story, tears gathered in her eyes and she paused, for a long moment staring into the distance, seemingly at nothing, before turning back to us. The boat carrying her family, she said, had capsized in the Mediterranean Sea. “Eight lives, gone just like that. For my whole life, I’ve seen Palestinians move from tragedy to tragedy, and from nakba to nakba.”

More than once in her life, it occurred to me, wars had pushed her, her children, and her grandchildren across borders and, in a distinctly embattled world, borders decided where she and her loved ones could possibly move, where they could live, and where they could die. I thought about the U.S. passport in my pocket, the relative ease with which I had crossed borders throughout my adult life, and the American tax dollars that helped doom Afaf to a life of permanent exile. She would be the first person I met who had lost loved ones simply looking to cross a border to find safety, but by no means the last.

Violent Borders

For tens of millions of people, borders are not merely places where the risk of violence is present. Borders are, by definition, violent. Borders are not merely crossed. Borders must be survived and endured. Borders are not only walls and razor wire. Borders are guards and police, surveillance cameras and drones, batons and bullets. For those tens of millions of people, borders don’t stop where one country ends and the next begins; they stalk and haunt across endless miles and years. Borders are both crime scenes and crimes, with nationalism the motive.

For people forced to flee, the violence doesn’t stop once they escape countries being bombed or economically strangled. The journey itself offers its own slate of dangers. The International Migration Organization has recorded more than 33,200 instances of refugees and migrants dying or going missing in the Mediterranean Sea alone since 2014. Between 1994 and 2024, rights groups estimate that more than 80,000 people died in the deserts or rivers on and around the U.S.-Mexico border.

Throughout the last decade, I’ve traveled along the European refugee trail, stopping off in countries across the Balkans and Central and Western Europe, while also reporting from American communities along the heavily militarized U.S.-Mexico border. Wherever I’ve gone, the displaced have horror stories to tell — of people drowned at sea, of migrants shot along borders, and others who simply disappeared along “the refugee trail.” At a shelter in Belgrade, Serbia, Afghans who had fled the fallout of the U.S. war in their country and walked the endless land route from Turkey spoke of the Bulgarian border police who had detained, threatened, or beaten them along the way. On the Serbian border with Hungary, Moroccans and Algerians told me of policemen who beat their feet with batons to deter them from ever trying to cross the border again. In Greece, young men from Sudan and Somalia — their countries no strangers to U.S. intervention — described the tear gas and rubber bullets they faced on the country’s northern border with Macedonia. In Turkey, Syrians told me about the dogs that Bulgarian border police sicced on them. In Arizona, people recalled walking for so long in the Mexican desert that the soles of their shoes tore apart.

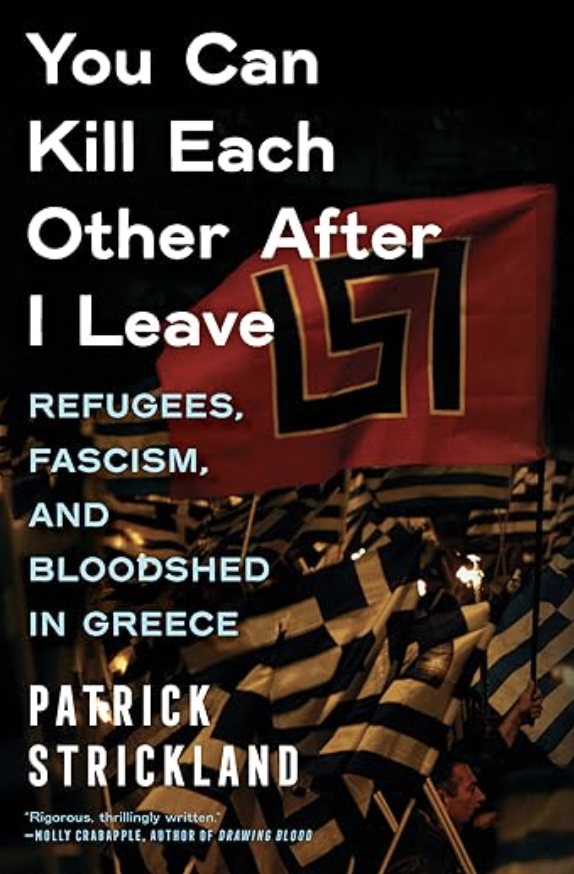

Perhaps more than anything else, the idea of strong borders has fueled the fascist-style surge that now grips the United States and significant parts of Europe. From the time Donald Trump first entered the Oval Office in January 2017, far-right and ultranationalist parties around Europe have also gained ground in ways that would once have been unimaginable — and where the far right has yet to take power, center-left and liberal parties have often swung hard to the right on their immigration and border enforcement policies.

In one breath, even Democratic Party officials in the United States, still singing praises of liberal democracy, are also promising to crack down on immigration and strengthen border enforcement in a desperate bid to appear tougher in the age of Donald Trump. In the United Kingdom, the center-left Labour Party ousted the Conservatives in 2024, only to put into practice anti-immigrant policies that align with those even further to the right, like Nigel Farage and his UK Independence Party. In Greece, even after the violent neo-Nazi Golden Dawn party was banned, following years of anti-immigrant violence, the nominally center-right New Democracy Party adopted and repackaged its rhetoric in slightly modified form, while placing a former fascist in charge of its migration ministry. From the United States to Europe, immigration is ever less often discussed as a humanitarian issue and ever more often described in terms of an “invasion,” functionally recasting desperate civilians as armed soldiers.

Politically, the invasion story is more easily digestible than the grim actual stories of displaced people. Unsurprisingly, it has found ever larger audiences. And consider that a grim irony, since so many of the people crossing into the U.S. and Europe, even before they faced deadly journeys at sea and militarized borders, were driven from their countries at least in part due to American and European involvement in mass violence and policies designed to foster economic collapse in their homelands.

Such invasion stories about immigrants are, of course, anything but new, after centuries in which a nationalistic desire for hard borders has undergirded so many claims that war and violence are necessary. In 1908, a decade before she herself was deported from the United States, the Lithuanian-American anarchist Emma Goldman pointed to the violence at the heart of such nationalism during a speech in San Francisco. “Patriotism assumes that our globe is divided into little spots, each one surrounded by an iron gate,” she told her audience. “Those who have had the fortune of being born on some particular spot consider themselves nobler, better, grander, more intelligent than those living beings inhabiting any other spot. It is, therefore, the duty of everyone living on that chosen spot to fight, kill, and die in the attempt to impose his superiority upon all the others.”

Hope in the Pushback

In the decade since I started covering migration and borders, I have also witnessed what resistance to the anti-immigrant far right might look like. In Greece, activists and volunteers, anarchists, socialists, and everyday people worked together to do what they could to offer an alternative to the grim realities displaced people were experiencing. On Greek islands like Lesbos, humanitarians gathered by the shore to help the displaced disembark from boats. Others headed out to sea to rescue people from sinking vessels. In Athens, anarchists and other leftists occupied abandoned buildings, refashioning them into squats that displaced immigrants could inhabit without the overcrowding and decrepit living conditions of the official camps. In Germany, everyday people opened their homes to newly arrived refugees. In Austin, Texas, the congregants of a church told me about how they had taken in asylum seekers facing deportation.

And today, Americans in cities from Chicago to Los Angeles have rallied to push back against the Trump administration’s immigration raids. Ever since an ICE agent shot and killed Renee Good in Minneapolis in January, ever more protesters have taken to the streets in growing numbers to voice their opposition to state-sanctioned murder and the Trump administration’s drive to carry out mass deportations fueled more by cruelty than any concern for the country’s safety. As the president deepens federal deployments and threatens to use the military against what he calls the “invasion from within,” those demonstrators undoubtedly understand that their own fates are wrapped up with those of immigrants and refugees. Squats, humanitarian aid, and mass protests may not stop the cruel wheels of the anti-immigrant political machine, but they do offer glimmers of hope at a time when hope is in short supply.

In the early months of 2026, that hope may be needed more than ever, in part because all too many Americans and Europeans continue to empower politicians who recycle the tired argument that, if there were fewer immigrants, life in their countries would be more prosperous and peaceful. In the lead-up to the 2024 election, Donald Trump bluntly assured Americans that immigrants were invaders who were “poisoning the blood of our country.” During the first year of his second term, his administration snatched international students off the streets, separated families, and shipped immigrants off to foreign prisons. Meanwhile, he continued to repeatedly tell Americans that they were being “invaded,” a story that comes with a painful body count, while courting what inevitably loiters behind nationalism and nativism: fear.

In her novel White Teeth, Zadie Smith put all of that in perspective this way: “But it makes an immigrant laugh to hear the fears of the nationalist, scared of infection, penetration, miscegenation when this is small fry, peanuts, compared to what the immigrant fears — dissolution, disappearance.”

Last year, the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) estimated that more than 122 million people across the world had been displaced as a result of war, violence, or persecution, a number that marked a decade-long high and was also the 10th consecutive year that the total number of people displaced across the globe had increased. Worse yet, war and military campaigns are still driving people from their homes globally.

Sooner than later, such wars and other disasters will result in yet more people seeking safety in Europe and the United States. When that happens, there is little doubt that far-right leaders, hoping to offload the blame for their own failures, will once again stand in front of us and claim that state violence is necessary to protect our country from an “invasion.” Then, you’ll have to make a choice: You can buy into the claim that the most powerful countries on the planet are the victims of invasions or remember that actual invasions and the military campaigns that create lethal cycles of mass displacement are happening in all too many places on this planet. That choice will determine just how much hope there is for a world where desperate people escaping disasters they had no hand in creating don’t have to consider crossing a manmade line a matter of negotiating their very survival.

Copyright 2026 Patrick Strickland

Via Tomdispatch.com

© 2026 All Rights Reserved

© 2026 All Rights Reserved