Guest Editor Fariba Amini writes:

I was going to write an article on the recent events in Iran, but in all honesty, my pen did not allow me. With the internet shut down in Iran, we have yet few images, but the news of hundreds killed breaks one’s heart. Blood is pouring onto Iran’s sidewalks.

Violence has been unprecedented on both sides, even though the protest started peacefully.

The Islamic Republic of Iran in its entirety is to be blamed, no question. Corruption, mismanagement, theft, suppression and the fall of the toman, have led to massive protests all over Iran. Sanctions of course have not helped. “People are exhausted,” as the seasoned Canadian reporter Lyse Doucet, author of The Finest Hotel in Kabul said after her recent visit.

The authorities have always reacted with brutality to demonstrations and protests, arresting thousands, torturing many and even executing several people. This time is no different. Israel meanwhile has been adamant in bringing down this Islamic Republic, with assassinations, with attacks on its nuclear sites, assassination of many of the top generals and nuclear scientists and fomenting dissent. Netanyahu and his gang are openly promoting the Shah’s son, Reza Pahlavi as their preferred leader of a transition period.

Instead of dealing firsthand with the economic situation, the IRI has been negligent and heedless to the plight of the people. When incompetence rules, people react. Sound familiar?

Instead of writing an article, I came across an informative article in French and decided to have it translated.

The author, Bernard Houcarde, is a social geographer who has written extensively on the geopolitics of modern Iran. He was the director of research on Iran at CNRS in Paris. He was stationed in Tehran at the French Institute between 1978 and 1993.

I thank my friend and colleague Dr. Mehdi Mousavi for this excellent translation. He received his PhD from the University of Delaware under the supervision of Professor Rudi Matthee under the title, French Diplomatic Odyssey, Continuity and Change in French Policies towards Iran (17-19th Centuries).

The Inevitable Transition in Iran

By Bernard Hourcade

Translated by Mehdi Mousavi.

( OrientXXI ) – Despite repression, protests are spreading across Iran. Yet the scenarios for a way out of the crisis remain uncertain and manifold: a U.S. military intervention, the return of the shah backed by Israel, an internal collapse leading to chaos, or the emergence of a strongman from within the regime itself.

For nearly half a century, the end of the Islamic Republic has repeatedly been predicted as imminent. Yet never have the often-contradictory forces of protest that forged a consensus to overthrow the Shah in 1979 come together again. Despite persistently harsh repression, popular uprisings in Iran are constant but fragmented, whether geographically or socially. Social groups rise one after another, each around specific demands and slogans, without seriously threatening those in power. In 2019, working-class suburbs rebelled against rising fuel prices; in 2022, young women took to the streets against the compulsory hijab; since December 28, 2025, shopkeepers and low-income heads of household have been mobilizing against hyperinflation.

However, this latest wave of unrest differs markedly from previous ones. Economic grievances are now directly tied to the functioning and political structure of the Islamic Republic itself. The unrest was sparked by conservative factions in Iran’s parliament blocking the draft budget for the Iranian year 1405 (beginning on March 21, 2026), which was submitted on December 23, 2025, by the reformist government of Massoud Pezeshkian.

This crisis is neither technical (fuel prices) nor legal (changing the law on the veil) but strikes at the very foundations of the regime: it concerns wealth, corruption, and therefore the legitimacy of the ruling elites. Resolving the current conflict thus goes beyond ideology, symbols, and slogans—whether against Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei or in favor of Reza Pahlavi, the son of the shah overthrown in 1979. It is an existential political crisis that can only be understood by closely examining the concrete balance of political forces within the country.

A dual exchange rate for the US dollar

The Islamic Republic has adopted a political system in which elites and institutions tied to the clergy—through religious foundations—and to the security apparatus, notably the Revolutionary Guards (IRGC), have captured the country’s wealth, fostering a liberalized economy that benefits an ultra-wealthy minority and fuels widespread public anger. Any political change is inseparable from an economic revolution that would dismantle these privileges that so deeply anger Iranians.

However, the country’s plutocratic management is reaching its limits, as the economic crisis crushing ordinary Iranians also weakens the state and calls into question its role as a regional power. In this context, the Islamic regime weakens the state while inflicting suffering on ordinary Iranians.

To avert the collapse of the state and the regime, reformist Prime Minister Massoud Pezeshkian unveiled a draft budget on December 23, 2025, proposing an end to multiple exchange rates and the preferential allocation of foreign currency—the official rate stood at 280,000 rials per dollar, compared with 1,400,000 on the “free” market. For decades, this system, controlled by regime-linked elites, had fueled a parallel economy and massive capital flight.[1]

To support his reform before parliament, President Pezeshkian highlighted, as an example, that this year, of the $12 billion allocated for food and medicine imports, $8 billion had been misappropriated, with only part of the goods imported while the rest of the funds were pocketed.

This project to “clean up” the economy went hand in hand with Iran’s ratification, in October 2025, of international conventions on banking transparency, in order to no longer appear on the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) blacklist, which had been blocking the country’s legal international transactions. In December, the Central Bank announced that it had closed 6,000 accounts suspected of money laundering—a measure that likely hit ordinary small traders who were importing electronics from Dubai illegally, rather than the wealthy or powerful individuals closely connected to the regime.

These financial reform initiatives, and the government’s obvious difficulties in enforcing them, proved the ruling authorities’ inability to manage the economy realistically. They also triggered a surge in the dollar’s exchange rate and sparked the revolt of merchants, marginalized by elite corruption and unable to manage hyperinflation.

The corporatist revolt of Tehran’s merchants quickly spread to their counterparts in smaller towns and then to all social groups that had been protesting for years, bolstered by the mobilization of previously cautious and conservative segments of society. To avoid a direct confrontation with the shopkeepers and a broader domestic social movement, the government—and even the Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei—initially declared that they “recognized” their demands, in an attempt to isolate them from “troublemakers,” that is, protesters with political agendas clearly supported from abroad, namely supporters of Reza Pahlavi. State crackdowns ultimately united the protesters around shared political demands directed against the regime as a whole.

The movement thus spread, but in a fragmented and spontaneous way, without mass demonstrations in major cities, due to a lack of clear political vision, networks, or leaders drawing on domestic social forces. Society remained divided and cautious, even as the Supreme Leader on January 9 ordered a massive crackdown that could backfire and threaten his hold on power.

Clearly, the divided reformist government lacks the means— and perhaps even the will— to implement its reforms. For the reformist government to gain legitimacy or be taken seriously, it must target the oligarchs at the heart of the regime. These oligarchs have accumulated privileges, political influence, and wealth through illicit means. Those who seek to salvage the regime would have to confront the oligarchs. With these reforms having failed, are there any other credible paths to pull Iran out of these crises?

Political divisions and deadlocks

The Islamic Republic is often identified with the “regime of the mullahs” and the Revolutionary Guards, the “regime’s armed wing.” These labels, however, obscure the differences in nature, culture, and interests that separate the clergy from the Revolutionary Guards. The rivalry between these two pillars of the Islamic Republic is a key factor in understanding its longevity and in envisioning possible paths out of the current crises.

The Revolutionary Guards, whose veterans pursued university studies after Iran-Iraq War, have demonstrated their skills in managing businesses (to their own benefit) and in high technology. Their successes, often achieved through illegal means, in nuclear programs, missile development, public works, and the management of major cities and enterprises confirm this. They know how to navigate the international economy, for example by circumventing U.S. economic sanctions. They are also seeking to recover from the failure of their regional ambitions following the collapse of the ‘Axis of Resistance’ against Israel.

The clergy, trained in religious schools, has sometimes evolved in the realm of ideas, but remains largely confined to a traditional and patriarchal form of Islam, out of step with contemporary Iranian society. By becoming directly involved in the management of the state, it has lost the social, economic, and even intellectual base that allowed it to mobilize the masses in 1979. Beyond a few slogans from the past, Islam plays little role in the political, security, economic, or geopolitical discourse shaping contemporary Iran—one of the most secularized countries in the Middle East. Yet, everyone is careful not to upset the public’s religious feelings, to keep the quiet support of people still attached to the Islamic tradition.

The alternation between “conservatives” and “reformists,” which for a long time allowed the Islamic Republic to function, now seems to have reached its limits. The ‘Thermidorian Reaction,’ long seen as a source of hope after Ruhollah Khomeini’s death, no longer functions.[2] Among the radical conservatives, notably represented by 2024 presidential candidate Saïd Jalili, the failures of the ‘Axis of Resistance’ and their strict, patriarchal interpretation of Islam have pushed them to take even harder positions. They support the Supreme Leader, whose death or forced departure would deprive them of an irreplaceable backing. On the other side, among reformists or “pragmatic” conservative Islamists who have recently united in a new party, debates and conflicts are intense as they seek a transition toward deep and inevitable political change that would preserve the country’s independence and avoid a radical revolution. Nevertheless, these political maneuvers appear to have run their course.

Facing internal political deadlock and a divided society, the Islamic Republic is reaching its limits. Systematic repression could even prove counterproductive, radicalizing the opposition and sparking criticism from within the regime itself. The stalemate is twofold: riots are being suppressed and have no clear political direction, while conservatives block budget reforms that could threaten them, and reformists lack the power—or the will—to push them through.

This political vacuum explains the success of Reza Pahlavi, exiled in the United States, who is the only opposition figure whose name is widely known among Iranians. He is well known in the media, supported by Persian-language outlets abroad with official, political—and possibly military—backing from Israel, and some support from the United States, which has also threatened to intervene in Iran’s political crisis. The son of the ruler overthrown in 1979 presents himself as the sole alternative to the Islamic Republic. His name has become a symbol for all opposition to the regime. But beyond the symbolism, nothing is clear—except for the prospect of even harsher repression, given that the protests are dispersed, poorly coordinated, and lack leadership or structured organization within the country.

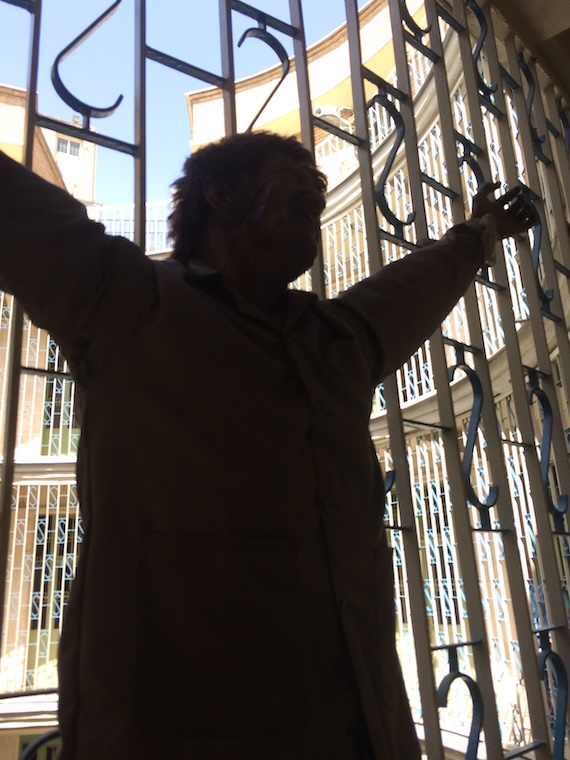

Ebrat Museum, at a facility formerly used to detain prisoners of conscience by SAVAK under Mohammad Reza Shah. Photograph 2019 by Fariba Amini.

This political landscape recalls 1978, when the Shah’s army was forced to allow massive demonstrations featuring portraits of Ruhollah Khomeini. Then in exile and still little known, Khomeini could rely on a strong network of supporters organized around the mosques. But the comparison has its limits, as Iran today has changed profoundly. Its population has developed political awareness and solid experience shaped by 45 years of the Islamic Republic. It has become republican and understands the cost of revolutions imported from abroad, notably in neighboring Iraq, “liberated” by the United States in 2003.[3] The question is less about when, and more about how, a deep political change—considered inevitable even within the current regime—will occur.

Toward divisions inside the regime?

To address immediately the internal and external crises that are dramatically weakening both the Iranian population and the state, the solution will probably need to come from within the current government itself, rather than from outside. Economist Saïd Leylaz, a close associate of former President Mohammed Khatami (1997–2005), is not the only one to publicly speak of the emergence of a “Bonaparte” figure within the current power structure: a strong figure capable of gaining popular support while securing the silence of the regime’s dignitaries and factions, in order to impose the economic reforms necessary for the survival of the state, as well as the measures of economic justice and freedoms demanded by Iranians.[4] This would involve judging and sanctioning corrupt elites— “cutting off the hands of thieves.” Such a profound change is far more difficult to achieve than removing the Supreme Leader.

This scenario recalls the rise to power in Saudi Arabia of Prince Mohammed bin Salman, who became crown prince and detained the kingdom’s most powerful figures. It may also evoke the ascension of Mikhail Gorbachev, General Secretary of the Communist Party, who oversaw the end of the USSR, or that of Deng Xiaoping, Mao Zedong’s successor, who turned the page on Maoism.[5] One can also think of Napoleon Bonaparte’s coup on 18 Brumaire, which ended the revolutionary period in France while preserving its achievements.

Even if no hypothesis can be ruled out after the United States’ capture of the president of Venezuela on January 3, 2026, or the attempts by the royalist opposition in exile—backed publicly by the United States and Israel—to capitalize on the uprisings, the dynamics of a credible and lasting transition are to be found within the country itself.

Translated and reprinted with the author’s permission from OrientXXI .

Notes

[1] Bijan Khajehpour, “Will Pezeshkian’s “economic surgery” save struggling Iranians?” Amwaj Media, January 7, 2026.

[2] Fariba Adelkhah, Jean-François Bayart and Olivier Roy, Thermidor en Iran, Éditions Complexe, 1992.

[3] Bernard Hourcade, Iran, paradoxes d’une nation, CNRS éditions, 2021.

[4] Said Leylaz, “Tehran’s method of governance has reached a dead end,” Euronews, January 5, 2026.

[5] Vali Nasr, “Iranians want their own Deng Xiaoping,” The Economist, December 9, 2025.

© 2026 All Rights Reserved

© 2026 All Rights Reserved