By Abrahm Lustgarten, Graphics by Lucas Waldron, Illustrations by Olivier Kugler for ProPublica

( ProPublica ) – As the planet gets hotter and its reservoirs shrink and its glaciers melt, people have increasingly drilled into a largely ungoverned, invisible cache of fresh water: the vast, hidden pools found deep underground.

Now, a new study that examines the world’s total supply of fresh water — accounting for its rivers and rain, ice and aquifers together — warns that Earth’s most essential resource is quickly disappearing, signaling what the paper’s authors describe as “a critical, emerging threat to humanity.” The landmasses of the planet are drying. In most places there is less precipitation even as moisture evaporates from the soil faster. More than anything, Earth is being slowly dehydrated by the unmitigated mining of groundwater, which underlies vast proportions of every continent. Nearly 6 billion people, or three quarters of humanity, live in the 101 countries that the study identified as confronting a net decline in water supply — portending enormous challenges for food production and a heightening risk of conflict and instability.

The paper “provides a glimpse of what the future is going to be,” said Hrishikesh Chandanpurkar, an earth systems scientist working with Arizona State University and the lead author of the study. “We are already dipping from a trust fund. We don’t actually know how much the account has.”

The research, published on Friday in the journal Science Advances, confirms not just that droughts and precipitation are growing more extreme but reports that drying regions are fast expanding. It also found that while parts of the planet are getting wetter, those areas are shrinking. The study, which excludes the ice sheets of Antarctica and Greenland, concludes not only that Earth is suffering a pandemic of “continental drying” in lower latitudes, but that it is the uninhibited pumping of groundwater by farmers, cities and corporations around the world that now accounts for 68% of the total loss of fresh water in those areas, which generally don’t have glaciers.

Groundwater is ubiquitous across the globe, but its quality and depth vary, as does its potential to be replenished by rainfall. Major groundwater basins — the deep and often high-quality aquifers — underlie roughly one-third of the planet, including roughly half of Africa, Europe and South America. But many of those aquifers took millions of years to form and might take thousands of years to refill. Instead, a significant portion of the water taken from underground flows off the land through rivers and on to the oceans.

The researchers were surprised to find that the loss of water on the continents has grown so dramatically that it has become one of the largest causes of global sea level rise. Moisture lost to evaporation and drought, plus runoff from pumped groundwater, now outpaces the melting of glaciers and the ice sheets of either Antarctica or Greenland as the largest contributor of water to the oceans.

The study examines 22 years of observational data from NASA’s Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment, or GRACE, satellites, which measure changes in the mass of the earth and have been applied to estimate its water content. The technique was groundbreaking two decades ago when the study’s co-author, Jay Famiglietti, who was then a professor at the University of California, at Irvine, used it to pinpoint where aquifers were in decline. Since then, he and others have published dozens of papers using GRACE data, but the question has always lingered: What does the groundwater loss mean in the context of all of the water available on the continents? So Famiglietti, now a professor at Arizona State University, set out to inventory all the land-based water contained in glaciers, rivers and aquifers and see what was changing. The answer: everything, and quickly.

Since 2002, the GRACE sensors have detected a rapid shift in water loss patterns around the planet. Around 2014, though, the pace of drying appears to have accelerated, the authors found, and is now growing by an area twice the size of California each year. “It’s like this sort of creeping disaster that has taken over the continents in ways that no one was really anticipating,” Famiglietti said. (Six other researchers also contributed to the study.) The parts of the world drying most acutely are becoming interconnected, forming what the study’s authors describe as “mega” regions spreading across the earth’s mid-latitudes. One of those regions covers almost the whole of Europe, the Middle East, North Africa and parts of Asia.

In the American Southwest and California, groundwater loss is a familiar story, but over the past two decades that hot spot has also spread dramatically. It now extends through Texas and up through the southern High Plains, where the Ogallala aquifer is depended on for agriculture, and it spreads south, stretching throughout Mexico and into Central America. These regions are connected not because they rely on the same water sources — in most cases they don’t — but because their populations will face the same perils of water stress: the most likely, a food crisis that could ultimately displace millions of people.

“This has to serve as a wake-up call,” said Aaron Salzberg, a former fellow at the Woodrow Wilson Center and the former director of the Water Institute at the University of North Carolina, who was not involved with the study.

Research has long established that people take more water from underground when climate-driven heat and drought are at their worst. For example, during droughts when California has enforced restrictions on delivery of surface water to its farmers — which the state regulates — the enormous agriculture enterprises that dominate the Central Valley have drilled deeper and pumped harder, depleting the aquifer — which the state regulates less precisely — even more.

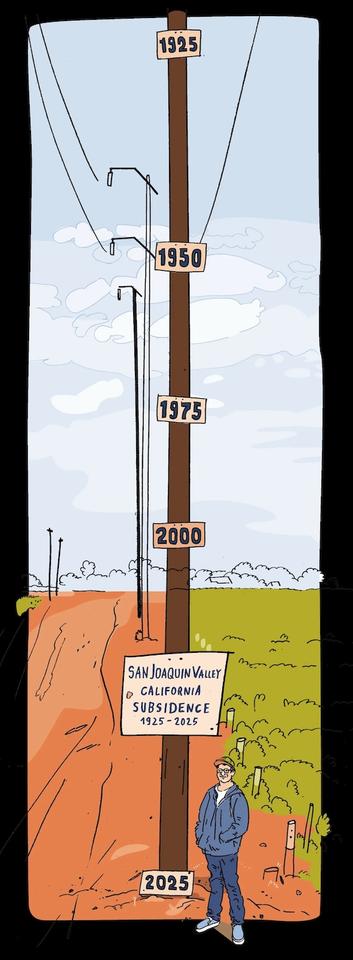

For the most part, such withdrawals have remained invisible. Even with the GRACE data, scientists cannot measure the exact levels or know when an aquifer will be exhausted. But there is one foolproof sign that groundwater is disappearing: The earth above it collapses as the ground compresses like a drying sponge. The visible signs of such subsidence around the world appear to match what the GRACE data says. Mexico City is sinking as its groundwater aquifers are drained, as are large parts China, Indonesia, Spain and Iran, to name a few. A recent study by researchers at Virginia Tech in the journal Nature Cities found that 28 cities across the United States are sinking — New York, Houston and Denver, among them — threatening havoc for everything from building safety to transit. In the Central Valley, the ground surface is nearly 30 vertical feet lower than it was in the first part of the 20th century.

When so much water is pumped, it has to drain somewhere. Just like rivers and streams fed by rainfall, much of the used groundwater makes its way into the ocean. The study pinpoints a remarkable shift: Groundwater drilled by people, used for agriculture or urban supplies and then discarded into drainages now contributes more water to the oceans than melting from each of the world’s largest ice caps.

People aren’t just misusing groundwater, they are flooding their own coasts and cities in the process, Famiglietti warns. That means they are also imperiling some of the world’s most important food-producing lowlands in the Nile and Mekong deltas and cities from Shanghai to New York. Once in the oceans, of course, groundwater will never again be suitable for drinking and human use without expensive and energy-sucking treatment or through the natural cycle of evaporating and precipitating as rain. But even then, it may no longer fall where it is needed most. Groundwater “is an intergenerational resource that is being poorly managed, if managed at all,” the study states, “at tremendous and exceptionally undervalued cost to future generations.”

That such rapid and substantial overuse of groundwater is also causing coastal flooding underscores the compounding threat of rising temperatures and aridity. It means that water scarcity and some of the most disruptive effects of climate change are now inextricably intertwined. And here, the study’s authors implore leaders to find a policy solution: Improve water management and reduce groundwater use now, and the world has a tool to slow the rate of sea level rise. Fail to adjust the governance and use of groundwater around the world, and humanity risks surrendering parts of its coastal cities while pouring out finite reserves it will sorely need as the other effects of climate change take hold.

If the drying continues — and the researchers warn that it is now nearly impossible to reverse “on human timescales” — it heralds “potentially staggering” and cascading risks for global order. The majority of the earth’s population lives in the 101 countries that the study identified as losing fresh water, making up not just North America, Europe and North Africa but also much of Asia, the Middle East and South America. This suggests the middle band of Earth is becoming less habitable. It also correlates closely with the places that a separate body of climate research has already identified as a shrinking environmental niche that has suited civilization for the past 6,000 years. Combined, these findings all point to the likelihood of widespread famine, the migration of large numbers of people seeking a more stable environment and the carry-on impact of geopolitical disorder.

Peter Gleick, a climate scientist and a member of the National Academy of Sciences, lauded the new report for confirming trends that were once theoretical. The ramifications, he said, could be profoundly destabilizing. “The massive overpumping of groundwater,” Gleick said, “poses enormous risk to food production.” And food, he pointed out, is the foundation for stability. The water science center he co-founded, the Pacific Institute, has tracked more than 1,900 incidents in which water supplies were either the casualty of, a tool for or the cause of violence. In Syria, beginning in 2011, drought and groundwater depletion drove rural unrest that contributed to the civil war, which displaced millions of people. In Ghana, in 2017, protesters rioted as wells ran dry. And in Ukraine, whose wheat supports much of the world, water infrastructure has been a frequent target of Russian attacks.

“Water is being used as a strategic and political tool,” said Salzberg, who spent nearly two decades analyzing water security issues as the special director for water resources at the State Department. “We should expect to see that more often as the water supply crisis is exacerbated.”

India, for example, recently weaponized water against Pakistan. In April, following terrorist attacks in Kashmir, Prime Minister Narendra Modi suspended his country’s participation in the Indus Waters Treaty, a river-sharing agreement between the two nuclear powers that was negotiated in 1960. The Indus system flows northwest out of Tibet into India, before turning southward into Pakistan. Pakistan has severely depleted its groundwater reserves — the region is facing one of the world’s most urgent water emergencies according to the Science Advances paper. The Indus has only become more essential as a supply of fresh water for its 252 million people. Allowing that water to cross the border would be “prejudicial to India’s interests,” Modi said. In this case, he wasn’t attempting to recoup water supply for his country, Salzberg said, but was leveraging its scarcity to win a strategic advantage over his country’s principal rival.

What’s needed most is governance of water that recognizes it as a crucial resource that determines both sovereignty and progress, Salzberg added. Yet there is no international framework for water management, and only a handful of countries have national water policies of their own.

The United States has taken stabs at regulating its groundwater use, but in some cases those attempts appear to be failing. In 2014, California passed what seemed to many a revolutionary groundwater management act that required communities to assess their total water supply and budget its long-term use. But the act doesn’t take full effect until 2040, which has allowed many groundwater districts to continue to draw heavily from aquifers even as they complete their plans to conserve those resources. Chandanpurkar and Famiglietti’s research underscores the consequences for such a slow approach.

Arizona pioneered groundwater regulations in 1980, creating what it called active management areas where extraction would be limited and surface waters would be used to replenish aquifers. But it only chose to manage the water in metropolitan areas, leaving vast, unregulated swaths of the state where investors, farmers and industry have all pounced on the availability of free water for profit. In recent years, Saudi investors have pumped rural water to grow feed for cattle exported back to the Arabian Peninsula, and hedge funds are competing to pump and sell water to towns near Phoenix. Meanwhile, four out of the original five active management areas are failing to meet the state’s own targets.

“They like to say, ‘Oh, the management’s doing well,’” Famiglietti said, but looking out over the next century, the trends suggest the aquifers will continue to empty out. “No one talks about that. I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say it’s an existential issue for cities like Phoenix.”

By Olivier Kugler

Both California and Arizona grow significant portions of America’s fruits and vegetables. Something has to give. “If you want to grow food in a place like California,” Famiglietti asked, “do you just bring in water? If we deplete that groundwater, I don’t think there’s enough water to really replace what we’re doing there.” The United States might not have much choice, he added, but to move California’s agriculture production somewhere far away and retire the land.

Chandanpurkar, Famiglietti and the report’s other authors suggest there are ready solutions to the problems they have identified, because unlike so many aspects of the climate crisis, the human decisions that lead to the overuse of water can be speedily corrected. Agriculture, which uses the vast majority of the world’s fresh water, can deploy well-tested technologies like drip irrigation, as Israel has, that sharply cut use by as much as 50%. When California farms reduced their take of Colorado River water in 2023 and 2024, the water levels in Lake Mead, the nation’s largest reservoir, jumped by 16 vertical feet as some 390 billion gallons were saved by 2025. Individuals can reduce water waste by changing simple routines: shortening showers or removing lawns. And cities can look to recycle more of the water they use, as San Diego has.

A national policy that establishes rules around water practices but also prioritizes the use of water resources for national security and a collective interest could counterbalance the forces of habit and special interests, Salzberg said. Every country needs such a policy, and if the United States were to lead, it might offer an advantage. But “the U.S. doesn’t have a national water strategy,” he said, referring to a disjointed patchwork of state and court oversight. “We don’t even have a national water institution. We haven’t thought as a country about how we would even protect our own water resources for our own national interests, and we’re a mess.”

July 25, 2025: This story originally included a quote from Jay Famiglietti characterizing Arizona’s water supply as facing total depletion by the end of the century. Famiglietti communicated a correction to that assertion to ProPublica, which failed to incorporate it before the story was published. The quote has been adjusted to reflect Famiglietti’s view that Arizona’s water supply will be diminished but may not disappear.

Data Source: Hrishikesh. A. Chandanpurkar, James S. Famiglietti, Kaushik Gopalan, David N. Wiese, Yoshihide Wada, Kaoru Kakinuma, John T. Reager, Fan Zhang (2025). Unprecedented Continental Drying, Shrinking Freshwater Availability, and Increasing Land Contributions to Sea Level Rise. Science Advances. https://www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.adx0298

Visual editing by Alex Bandoni. Additional design and development by Anna Donlan.

Via ProPublica

Abrahm Lustgarten

I report on climate change and how people, companies and governments are adapting to it.

I’m discreet and handle confidential communications and sources with extreme care.

Lucas Waldron

Lucas Waldron is a graphics editor at ProPublica.

© 2026 All Rights Reserved

© 2026 All Rights Reserved