The third quatrain attributed to Omar Khayyám in FitzGerald’s first edition of the Rubáiyát is from the manuscript dated 1460 in the Bodleian Library, Oxford, which I translated in full (see below).

III.

And, as the Cock crew, those who stood before

The Tavern shouted — “Open then the Door!

“You know how little while we have to stay,

“And, once departed, may return no more.”

According to Arberry (Romance p. 111), who transliterated it, this is Bodleian 140:

آنند که ز پیش رفته اند ای ساقی

در خاک غرور خفته اند ای ساقی

رو باده خور و حقیقت از من بشنو

باد است هر آنچه گفته اند ای ساقی

ānān ki ɀi pīsh rufta and ai sāqī

dar khāk-i ghurūr khufta and ai sāqī

raw bāda khwur ū ḥaqīqat aɀ man bi-shinaw

bād-ast har ān-chi gufta and ai sāqī

I translated it as 139 in my book, in blank verse without rhyme.

Literally, the original if we put it into prosaic prose as A. J. Arberry did, goes something like this:

Those who swept up (the tavern) before, wine-server

have fallen asleep in the dust of boastfulness, wine-server!

Go, drink wine, and hear the truth from me:

Everything they told us was just wind.

—-

Order Juan Cole’s contemporary poetic translation of the Rubáiyát from

or Barnes and Noble.

or for $16 at Amazon Kindle

——-

A whole genre developed in medieval Persian poetry around the sāqi, the young lad who brought wine to patrons of the tavern, explains Paul Losensky. He wrote, “the speaker, seeking relief from his hardships, losses, and disappointments, repeatedly summons the sāqi … or cupbearer to bring him wine and the … singer to provide a song.”

In his Book of Alexander, the poet Neẓāmi (d. 1209), Losensky says, “calls on the cupbearer for wine and inspiration and reflects on some of the common themes of … wisdom literature -— the brevity of human life, the fickleness of fate, and the necessity of severing worldly attachments.”

This quatrain plays on these themes. Here, the patron at the tavern complains about what we might call the busboys there, who swept the floors and cleaned off the tables. These elderly persons whispered a lot of bunkum over the years into the ears of the men who drank there, and now are six feet under. These departed busboys symbolize the commonplaces people pass on about the future, about there being a heaven and a hell and an afterlife.

So in the way of the sāqi-nāma or Book of the Wine-Server, the poet here complains about the now-dead old janitorial staff to the boy who brings cups of wine. They were filled with delusion, or vainglory or boastfulness (ghurūr). No one is getting back up out of the grave once interred, the poet implies. FitzGerald got this theme right, though he added in a lot of his own imagery and color.

In the original, only wine can assuage the pain of being told this pack of metaphysical lies by people one had trusted.

This quatrain puts the stock images about the sāqi to an ironic use. The poet is not complaining about the travails of life but about the supposed verities of religion, which holds out false hope of a resurrection after death. Since we have only one life that is often painful, the poet recommends, we may as well self-medicate a bit.

Losensky notes that the complaint to the wine-server was often set in a party or a courtly banquet. In the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, however, the setting is usually a broken-down wine-house. He writes, “Such parties by their very nature depart from the normal routines of daily life and violate the precepts of Islamic law.” What better place than a forbidden dive to reveal the bankruptcy of religious doctrine, the quatrain seems to ask.

But the tavern and its fare took on “transcendental and transgressive implications,” especially with the rise of Sufi poetry that interpreted wine as a symbol of ecstatic union with the divine. Losensky continues, “Utilized in every poetic genre and form, wine emerged as one of the most protean and adaptable image complexes in the literary tradition. It could provide solace for the outcast, open the doors of mystical transcendence, or sanctify the communal festivities of the court.”

Here, it provided solace to the village atheist, cursed with a gimlet eye and an inability to believe any longer in what I translated as the “hot air” of pious common wisdom.

The Edwardian satirist and short story writer H. H. Munro took the pen name Saki (i.e. sāqi) under FitzGerald’s influence.

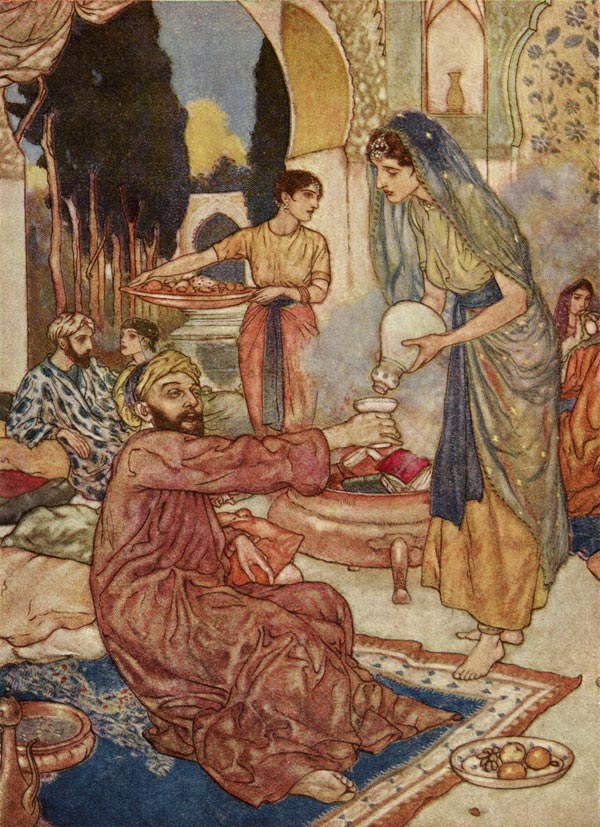

Artist Edward Dulac back at the turn of the twentieth century produced many illustrations of the Rubáiyát, imagining the sāqis as women — a Western conceit, though there may have been Christian and Parsi female wine servers in minority-owned taverns.

Edward Dulac, “A New Marriage. Public Domain.

In this series:

FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám 1:1

“Awake my little ones and fill the Cup!” FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám 1:2

“Those who Stood before the Tavern” – FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám 1:3

Now the New Year is Reviving old Desires: FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám 1:4

“But still the Vine her ancient Ruby Yields:” Fitzgerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám 1:5

“Red Wine!” – the Nightingale cries to the Rose: FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám 1:6

© 2026 All Rights Reserved

© 2026 All Rights Reserved