Revised.

Quatrain 16 in the first edition of Edward FitzGerald’s translation of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám underlines that life is fleeting for everyone, even the rich and powerful, and even for monarchs. FitzGerald was an “entrepreneurial Radical” in Victorian terms, who disliked the aristocracy and favored the republican form of government for newly established nation-states in Europe such as Italy. Singling out kings as a demonstration case of how time holds still for no one may have been a way of subtly expressing this republicanism.

XVI.

- Think, in this batter’d Caravanserai

Whose Doorways are alternate Night and Day,

How Sultán after Sultán with his Pomp

Abode his Hour or two, and went his way.

The original was identified by A.J. Arberry as no. 98 in the Calcutta manuscript that Edward Cowell sent back to FitzGerald in 1857. It can now be found here.

این کهنه رباط را که عالم نام است

وآرامگه ابلقِ صبح و شام است

بزمیست که واماندۀ صد جمشید است

قصریست که تکیهگاه صد بهرام است

My literal translation in iambic heptameter would go this way:

This ancient caravanserai whose nickname is “the world”

provides a dappled refuge for each morning and each eve.

It is a banquet that left a hundred Jamshids behind.

It is a palace where a hundred Bahrams took their rest.

—-

Order Juan Cole’s contemporary poetic translation of the Rubáiyát from

or Barnes and Noble.

or for $16 at Amazon Kindle

——

The word for caravanserai here in the original is ribāṭ, which is discussed by J. Chabbi in The Encyclopedia of Islam. In the early centuries of Islam it referred to a military garrison where troops were stationed. However, because it was secure, trading caravans began stopping off at such places, staying the night on their way to their destination. So the word came to have the connotation of inn or caravanserai. In the 1100s and 1200s some ribāṭs began being used as Sufi centers, which established them as a separate space than the mosque, and under the control of spiritual adepts rather than legalistic clergy. The Turkish word khaneqah was also used for such mystical places of retreat.

Here, FitzGerald made a note that the word means caravanserai, and that is certainly correct. For the poets, a caravan is a symbol of impermanence, since it stays on the move.

The great mystic Jalal al-Din Rumi wrote, as well

بس رباطی که بباید ترک کرد

تا بمسکن دررسد یک روز مرد

Many a caravan you must forsake

until you one day reach the dwelling-place.

For Rumi, a pious Sufi, the dwelling-place or permanent abode is union with the divine, whereas in this world of gross matter we just stop off at temporary inns along the spiritual path.

We find a similar trope in Baba Afzal Kashani,

دنیا چو رباط و ما در او مهمانیم

تا ظن نبری که ما در او میمانیم

در هر دو جهان خدای میماند و بس

باقی همه کل من علیها فانایم

The world’s a caravanserai and we’re

its guests; so don’t imagine we’ll stay long.

In both these worlds it’s only God that stays

The rest are but “All on it are fleeting.”

The last quotation in this quatrain is from the Qur’an, 55:26, meaning “all on the surface of the earth are impermanent.” It illustrates that the emphasis on the ephemerality of all things found both in mystical and secular Persian poetry has roots in the Muslim scripture. Scripture and the pious drew a different lesson from it than did the secular-minded, though. For the latter, the lesson was that one may as well enjoy the good things of life, since it won’t last long, and they doubted there is an afterlife.

Baba Afzal Kashani (d. c. 1213 or 1214) was a spiritual philosopher and an acknowledged master of the Persian quatrain.

The great William Chittick writes of him,

- “various passages in his prose works point to the spiritual benefits the traveler (sālek)—a favorite Sufi term—will gain by studying; e.g., “He will find his own self, which is the treasury of the realities of all things and the leaven (māya) of infinite existence” (Moṣannafāt, p. 149; cf. pp. 321, 724). Bābā Afżal alludes in several places to the knowledge he has acquired through purifying his own soul; e.g., God gave him familiarity with the radiance of His own Being, making him into a mirror that reflected the whole of the universe (ibid., p. 83; cf. p. 259). In a letter he mentions spending sixty years in the world’s darkness and discovering the water of life, which is intellect (ʿaql, ḵerad). “Since my tongue has tasted intellect’s sweetness and savor, I have taken up residence at its wellspring” (ibid., pp. 698-99).”

In this quatrain of Khayyam, unlike in the very next stanza, FitzGerald did not name Jamshid and Bahram V as kings, using the vague “How Sultan after Sultan with his Pomp . . .” But they are referred to in the Persian quatrain on which he based 1:16.

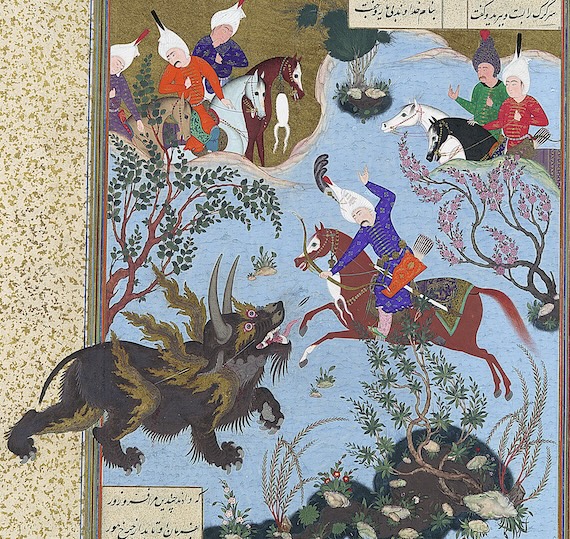

The Metropolitan Museum gives us a glimpse of Bahram’s later career as a hero of fable, telling us about a royal illustration of one of his adventures:

- “Shah Shangul asked Bahram to rid the world of a monstrous rhino‑wolf, which tore the hearts from lions and the skin from leopards. Bahram strung up his bow and sped toward the rhino‑wolf, pouring a mighty hail of arrows onto the beast. In this painting, the image of the rhino‑wolf breaks through the rulings of the painting into the margins, lending the composition dynamism and suggesting the extension of the setting beyond the confines of the page.”

Detail. “Bahram Gur Slays the Rhino-Wolf”, Folio 586r from the Shahnama (Book of Kings) of Shah Tahmasp, by Abu’l Qasim Firdausi. Iranian Painting attributed to ‘Abd al-‘Aziz. Workshop director Aqa Mirak. Iranian. ca. 1530–35. Opaque watercolor, ink, silver, and gold on paper Metropolitan Museum.

© 2026 All Rights Reserved

© 2026 All Rights Reserved