The tenth quatrain in the first edition of Edward FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám continues the theme of the irrelevance of political power to happiness, which lies instead in love. The Persian originals make clear the meaning here, which is a little cryptic in FitzGerald’s rendering.

X.

With me along some Strip of Herbage strown

That just divides the desert from the sown,

Where name of Slave and Sultán scarce is known,

And pity Sultan Mahmud on his Throne.

The previous stanza asked the reader to “leave” the ancient Iranian kings and heroes, and to “heed them not.” Here, we “pity” Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni on his throne because he does not have the lover that Khayyam has, whom he has to sneak out to meet beyond the cultivated land of the village where no one will see them.

A. J. Arberry (Romance of the Rubáiyát, 199) points out that the phrase “Strip of Herbage” is obviously a translation of the Persian “Lab-i kisht,” the “edge of cultivated land.” FitzGerald in his notes says that he saw it a lot in the poetry.

This phrase occurs in the first two lines of the Bodleian manuscript no. 25 (my 24):

در فصل بهار اگر بتی حور سرشت

پر می قدحی دهد مرا بر لب کشت

I translated it non-literally as

“If an earthly angel offered me a cup of wine

as we two sat along the river bank in spring . . .”

transliteration:

dar fasl-e bahār agar botī hūr-seresht

por mey qadahi dahad marā bar lab-e kesht

“Lab” in Persian is lip and is a cognate with the English word. In linguistics, “labial” means “uttered with the participation of one or both lips.”

“Kesht” or cultivated land in Persian is a cognate with the Latin cultura and the origin of our English word culture.

The image here is sneaking off to the dividing line between inhabited and wild spaces, where the lovers won’t be seen. This imagery would have resonated with Americans in the age of the western frontier. I figured in our contemporary urban civilization, more people have experience with a land/ water demarcation between inhabited spaces and nature, so I set the picnic on a riverbank.

My phrase “earthly angel” condenses references in the original to “bot” and “hur” or houri. bot, pronounced boat, in Persian means “idol,” as in pagan idol, and derives from the Sanskrit Buddha, since the Iranian Muslims encountered Buddhist temples as they conquered Khorasan, Afghanistan and what is now Pakistan. Poets took it up in exactly the way our Hollywood did, as a sex symbol — an “idol” was a beautiful beloved.

Merriam-Webster defines houri as “1: one of the beautiful maidens that in Muslim belief live with the blessed in paradise. 2: a voluptuously beautiful young woman.” Going into all that would be an essay in itself. Just to say that the Persian poets often used definition no. 2 here.

Hence my “earthly angel.”

—-

Order Juan Cole’s contemporary poetic translation of the Rubáiyát from

or Barnes and Noble.

or for $16 at Amazon Kindle

——

Edward Heron-Allen suggested that the second two lines come from second two lines of a poem in the Bodleian manuscript, no. 155 (my 154):

و آنکه من و تو نشسته در ویرانی

عیشی بود آن، نه حد هر سلطانی

This poem talks about two lovers planning a picnic, saying if we could get hold of a loaf of bread, some lamb kebabs and some wine,

“and we were snuggling in the wilderness–

we’d put to shame the pomp of any court.”

transliteration:

va ān keh man o to neshesteh dar virānī

ʿīshī bovad ān, na ḥadd-e har solṭānī

So that is why Mahmud is to be pitied — his magnificent court cannot measure up to the simple pleasures of a humble meal eaten by two lovers who can then snuggle with one another, away from prying eyes.

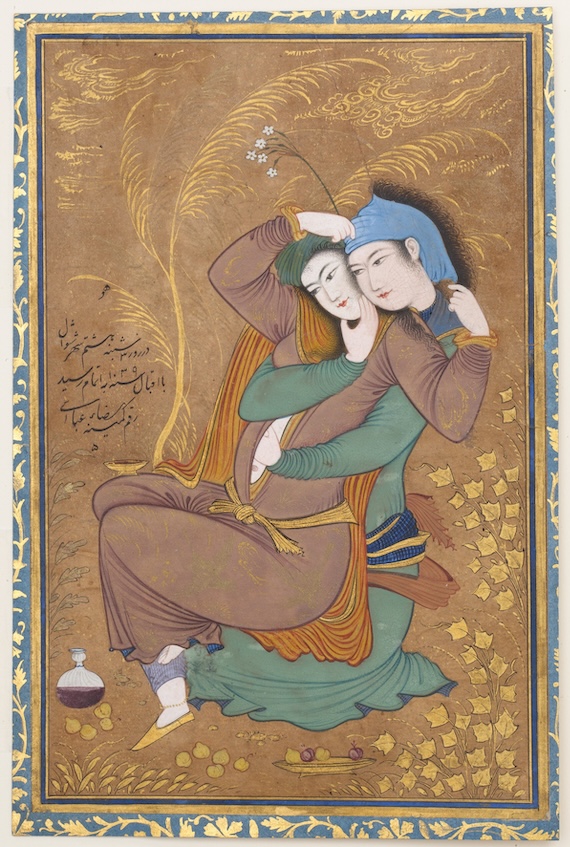

“The Lovers,” by Riza-yi ‘Abbasi (Iranian, ca. 1565–d. 1635), dated 1039 AH/ 1630 CE, Isfahan. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Mahmud is not mentioned by name in these particular originals, but he was an epic figure in Persian poetry whom FitzGerald would have met with in his reading in this literature, including no. 92 of the Calcutta manuscript of the Rubaiyat, as I discussed here.

For more commentaries on FitzGerald’s translations of the Rubáiyát, see

FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám: Commentary by Juan Cole with Original Persian

© 2026 All Rights Reserved

© 2026 All Rights Reserved