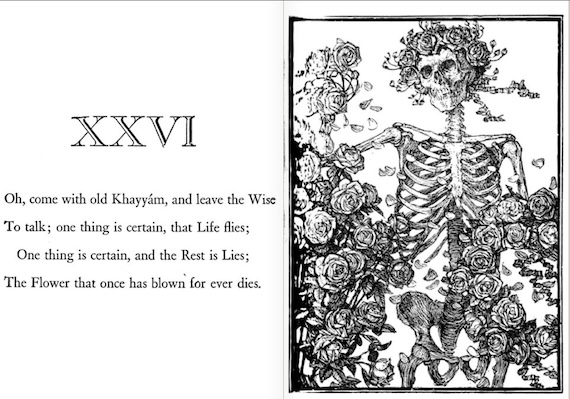

I am reprinting here my blog entries from Informed Comment that serve as an extended commentary on Edward FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám. The original entry is hyperlinked in the title. For each quatrain, I provide the Persian originals as far as they can be discerned. In about half of the cases, that is straightforward since he translated a complete stanza. In the other half, he combined lines from two different poems or riffed loosely based on one or more poems. Tracing the originals was largely the work of Edward Heron-Allen and A. J. Arberry (The Romance of the Rubáiyát), though I add some possibilities. I also comment on distinctive conceptions and poetic images in the context of Persian literature. I identify persons named, whether legendary or heroic, and explain their significance for the poetry. I give links to the relevant scholarship. I know there are still fans of the Rubáiyát out there, who yearn for this level of detail and texture in approaching the poems. More information can be found in my own translation of this poetry, to which I appended a long historical essay.

——

Order Juan’s new translation of the Rubáiyát from

or Barnes and Noble.

or for $16 (right now) at Amazon Kindle

—–

FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám 1:1

British man of letters Edward FitzGerald translated the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám from two Persian manuscripts and published it in 1859. He had substantial help from young Orientalist Edward Cowell, who discovered a manuscript of the Rubáiyát dated 1460 CE in the Bodleian Library at Oxford. Rubáiyát means “quatrains,” and in Persian poetry they consist of four lines with an aaba rhyme scheme (older ones had aaaa, but that was considered too difficult to achieve).

In FitzGerald’s first edition (there were three subsequent ones, with additions and changes), the first quatrain goes this way:

I.

Awake! for Morning in the Bowl of Night

Has flung the Stone that puts the Stars to Flight

And Lo! the Hunter of the East has caught

The Sultan’s Turret in a Noose of Light

This Persian original is identified by A. J. Arberry as Calcutta 137. From how Arberry describes it, I believe this is the original:

خورشيد كمند صبح بر بام افكند

كيخسرو روز باده در جام افكند

مي خور كه منادي سحرگه خيزان

آوازه اشربو در ايام افكند

I present below a fairly literal translation of the Persian, which I’m able to do in part because I have a better text than FitzGerald did. Since I’m trying to stay close to the original, unlike FitzGerald (whose poetry is genius), I am not trying to replicate the Persian aaba rhyme scheme, satisfying myself with abca instead. I do put it in iambic pentameter, the meter FitzGerald used:

When sunrise lassoes roof tops with its rays,

and morning wine fills Khosrow’s royal cup —

then sip a fine Shiraz – dawn’s herald has

proclaimed the call “Drink up!” throughout the days.

Transliteration:

Khorshīd kamand-e sobh bar bām afkand

Kaykhosrow-e rūz bāde dar jām afkand

May khor ke monādī-ye sahar-gah khīzān

āvāzah-‘e “ishrabū!” dar ayyām afkand

FitzGerald’s “hunter of the east” is Kay-Khosrow, the Sasanian Emperor Khosrow II (d. 628), who conquered much of the known world from Central Asia to Egypt and fatally weakened the Eastern Roman Empire.

Ancient Zoroastrians, the pre-Islamic religion of Iran, had a custom of drinking a cup of wine on rising at dawn, and it worked its way into even Islamic poetry. Arab warriors also drank wine when they rose, according to the ancient poetry of the Mu`allaqat, to gain some liquid courage for the battle to come. But I think this wine-drinking at dawn is of the Iranian sort, more genteel and urbane.

The image of the dawn having a crier or munadi that commands ishrabu, “drink up” in Arabic, is a piece of irreverence, since in Muslim societies at dawn the caller to prayer or muezzin melodiously instructs people to rise and pray.

Sufis interpreted wine, however, as a symbol for union with God, and so from that point of view the muezzin’s call to prayer is a summons to an inebriating spiritual communion with divine, hence “wine.”

Personally, I think in the corpus of Persian poetry attributed to Omar Khayyam, the wine is just wine and a kind of medieval Muslim secularism is being celebrated.

This poem is not in my own translation of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, since I stuck to the early 1460 manuscript in the Bodleian and I consider the Calcutta manuscript to be late and full of Mughal-era Indian verse (not that there is anything wrong with that).

“Awake my little ones and fill the Cup!” FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám 1:2

Edward FitzGerald, who published the first edition of his translation of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám in 1859, arranged the poems to unfold over a day in the life of the protagonist, beginning with a rowdy morning, as explained earlier. The second quatrain in his first edition is this:

II.

Dreaming when Dawn’s Left Hand was in the Sky

I heard a Voice within the Tavern cry,

“Awake, my Little ones, and fill the Cup

“Before Life’s Liquor in its Cup be dry.”

The original, which was also in FitzGerald’s Calcutta manuscript, was published by E. H. Whinfield in his Persian-English edition of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, as poem number 1:

آمد سحری ندا ز میخانهٔ ما

کای رند خراباتی دیوانهٔ ما

برخیز که پر کنیم پیمانه ز می

زان پیش که پر کنند پیمانهٔ ما

FitzGerald’s version is gentler and more genteel than the original, perhaps recalling his camaraderie with young Cambridge undergraduate men such as William Makepeace Thackeray.

This poem is not in the 1460 Bodleian manuscript on which I based my own translation, so it isn’t in my book. I have played around with this one, doing it as free verse and as a more formal Persian quatrain (rubá`í)

Here’s the latter:

A shout at dawn and a panic attack:

“You crazy rascal in this run-down shack,

get up and finish off those dregs of wine —

before our time is up and we’re called back.”

(transliteration:)

Āmad saharī nedā ze meyḵānah-‘e mā

K’āy rand-e ḵarābātī-ye dīvānah-‘e mā

Barkhīz ke por konīm peymānah ze mey

Zān pīsh ke por konand peymānah-‘e mā

FitzGerald had the scene right — drinking buddies frequenting a tavern have drunk themselves to sleep. Now it is dawn of the next day, and there is still wine in their cups, and they fear it will go to waste — just as there is a danger of their lives coming to an end before they have experienced life fully.

The tavern is at first called a maykhaneh a wine-house, but then kharabat, literally ruins. Drinking establishments were illicit in Muslim societies, though some rulers gave them wide latitude while others cracked down on them. But because they were in ill repute with respectable Muslim society, they tended to be owned by Christians or Parsis (Zoroastrians), and to be located in the disreputable part of town. Thus, they were in broken-down buildings or kharabat.

The unidentified voice addresses the dozing protagonist, calling him a rend or rapscallion or rascal and “crazy” or “wild” divaneh.

The late Franklin Lewis told us that the stock figure of the rend in Persian poetry, “variously translated in English as “rake, ruffian, pious rogue, brigand, libertine, lout, debauchee,” is the very antithesis of establishment propriety.”

He went on, speaking specifically of the poetry of Hafez of Shiraz (d. 1390),

- “we find figures of counter-culture and disrepute, including beggars (gadā, faqir, mofles), qalandars [wandering Sufi dervishes], and the characters who haunt the “ruins” (ḵarābāt). These ruins are scenes of illicit pleasure, occupied by drinkers and drunkards, the wine seller and wine server (sāqi), the Magian [Parsi or Zoroastrian] elder (pir-e moḡān) and Magian ephebe (moḡ-bačča), and the beloved (šāhed,delbar, maʿšuq, etc.). Chief among the anti-establishment figures is the rend, an irreligious alter-ego to Hafez’s more reputable persona, a safety valve saving him from the sanctimonious self-righteousness that characterizes the religious authorities”

Lewis noted that Hafez sometimes adopts the pose of the respectable urbane Muslim, or apparently veers into Muslims spirituality of a Sufi sort, but at others celebrates the rend.

I have sometimes thought that the rend in this sense is what happens to respectable American Christians at a Las Vegas stag party.

The quatrains attributed to Omar Khayyám inhabit that same universe, of ambiguity, though they on the whole are far more openly disreputable than anything in Hafez, and are expressed in cruder and less lofty terms.

One purpose of the rend was to bash hypocrisy. The spiritual school of the Malamatiya [“self-blame”] taught disciples to fear pride in good works, and so openly drinking wine, for instance, could humble them and convince the public that they were abject. Since no one attains to true piety and spirituality, they felt, it was better to suffer insults than to have people imagine them to be holy.

FitzGerald’s teasing “little ones,” recalling the affectionate forms of address in the homosocial spaces of Victorian male British literary gatherings, does not convey the disreputable overtones of the original rend. And while Thackeray in Paris may have acted crazily when FitzGerald accompanied him there in their youth, the “craziness” envisaged in this quatrain was of a different order entirely.

—

“Those who Stood before the Tavern” – FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám 1:3

The third quatrain attributed to Omar Khayyám in FitzGerald’s first edition of the Rubáiyát is from the manuscript dated 1460 in the Bodleian Library, Oxford, which I translated in full (see below).

III.

And, as the Cock crew, those who stood before

The Tavern shouted — “Open then the Door!

“You know how little while we have to stay,

“And, once departed, may return no more.”

According to Arberry (Romance p. 111), who transliterated it, this is Bodleian 140:

آنند که ز پیش رفته اند ای ساقی

در خاک غرور خفته اند ای ساقی

رو باده خور و حقیقت از من بشنو

باد است هر آنچه گفته اند ای ساقی

ānān ki ɀ pīsh rufta and ai sāqī

dar khāk-i ghurūr khufta and ai sāqī

raw bāda khwur ū ḥaqīqat aɀ man bi-shinaw

bād-ast har ān-chi gufta and ai sāqī

I translated it as 139 in my book, in blank verse without rhyme.

Literally, the original if we put it into prosaic prose as A. J. Arberry did, goes something like this:

Those who swept up (the tavern) before, wine-server

have fallen asleep in the dust of boastfulness, wine-server!

Go, drink wine, and hear the truth from me:

Everything they told us was just wind.

—-

Order Juan Cole’s contemporary poetic translation of the Rubáiyát from

or Barnes and Noble.

or for $16 at Amazon Kindle

——-

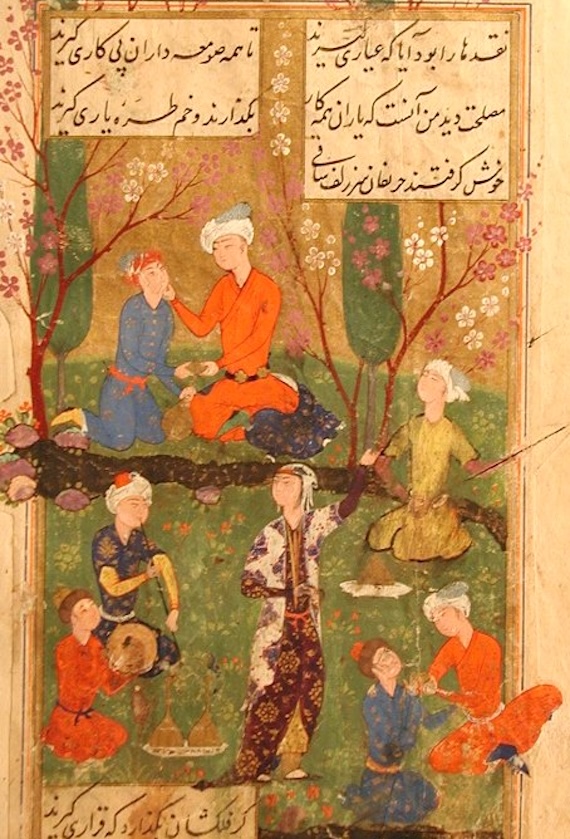

A whole genre developed in medieval Persian poetry around the sāqi, the young lad who brought wine to patrons of the tavern, explains Paul Losensky. He wrote, “the speaker, seeking relief from his hardships, losses, and disappointments, repeatedly summons the sāqi … or cupbearer to bring him wine and the … singer to provide a song.”

In his Book of Alexander, the poet Neẓāmi (d. 1209), Losensky says, “calls on the cupbearer for wine and inspiration and reflects on some of the common themes of … wisdom literature -— the brevity of human life, the fickleness of fate, and the necessity of severing worldly attachments.”

This quatrain plays on these themes. Here, the patron at the tavern complains about what we might call the busboys there, who swept the floors and cleaned off the tables. These elderly persons whispered a lot of bunkum over the years into the ears of the men who drank there, and now are six feet under. These departed busboys symbolize the commonplaces people pass on about the future, about there being a heaven and a hell and an afterlife.

So in the way of the sāqi-nāma or Book of the Wine-Server, the poet here complains about the now-dead old janitorial staff to the boy who brings cups of wine. They were filled with delusion, or vainglory or boastfulness (ghurūr). No one is getting back up out of the grave once interred, the poet implies. FitzGerald got this theme right, though he added in a lot of his own imagery and color.

In the original, only wine can assuage the pain of being told this pack of metaphysical lies by people one had trusted.

This quatrain puts the stock images about the sāqi to an ironic use. The poet is not complaining about the travails of life but about the supposed verities of religion, which holds out false hope of a resurrection after death. Since we have only one life that is often painful, the poet recommends, we may as well self-medicate a bit.

Losensky notes that the complaint to the wine-server was often set in a party or a courtly banquet. In the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, however, the setting is usually a broken-down wine-house. He writes, “Such parties by their very nature depart from the normal routines of daily life and violate the precepts of Islamic law.” What better place than a forbidden dive to reveal the bankruptcy of religious doctrine, the quatrain seems to ask.

But the tavern and its fare took on “transcendental and transgressive implications,” especially with the rise of Sufi poetry that interpreted wine as a symbol of ecstatic union with the divine. Losensky continues, “Utilized in every poetic genre and form, wine emerged as one of the most protean and adaptable image complexes in the literary tradition. It could provide solace for the outcast, open the doors of mystical transcendence, or sanctify the communal festivities of the court.”

Here, it provided solace to the village atheist, cursed with a gimlet eye and an inability to believe any longer in what I translated as the “hot air” of pious common wisdom.

The Edwardian satirist and short story writer H. H. Munro took the pen name Saki (i.e. sāqi) under FitzGerald’s influence.

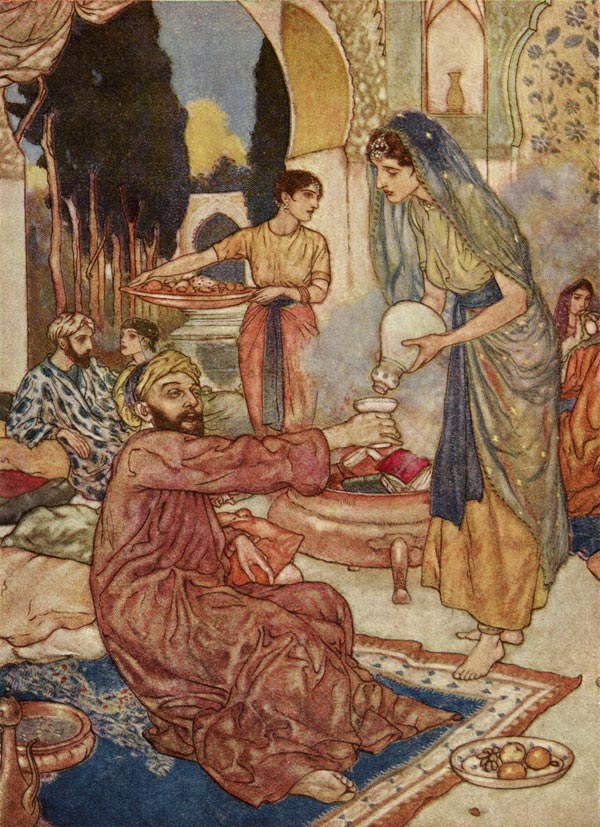

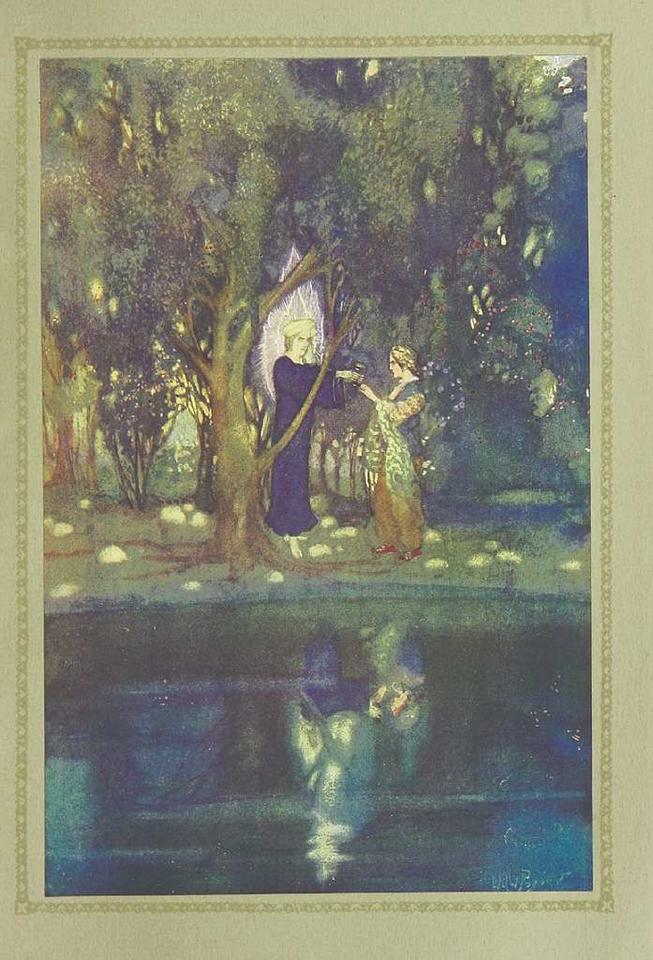

Artist Edward Dulac back at the turn of the twentieth century produced many illustrations of the Rubáiyát, imagining the sāqis as women — a Western conceit, though there may have been Christian and Parsi female wine servers in minority-owned taverns.

Edward Dulac, “A New Marriage. Public Domain.

Now the New Year is Reviving old Desires: FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám 1:4.

The fourth quatrain in Edward FitzGerald’s 1859 first edition of The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám is:

IV

Now the New Year is reviving old Desires,

The thoughtful Soul to Solitude retires,

Where the white hand of Moses on the Bough

Puts out, and Jesus from the Ground suspires.

اکنونکه جهانرا بخوشی دسترسیست

هر زنده دلی را سوی صحرا هوسیست

بر هر شاخی طلوع موسی دستیست

در هر نفسی خروش عیسی نفسیست

This is 13 of the Bodleian manuscript and #12 in my The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, a New Translation from the Persian, which also has a fascinating historical exploration of where this poetry came from and its influence through the ages.

Heron-Allen’s literal translation is:

Now that there is a possibility of happiness for the world,

every living heart has yearnings toward the desert;

upon every bough is the appearance of Moses’ hand;

in every breeze is the exhalation of Jesus’ breath.

Transliteration:

aknun ke jahanra bekhoshi dastrasist,

har zendeh deli ra suye sahra havasist.

bar har shakhi tolu-e musa dastist,

dar har nafasi khorush-e isa nafsist.

I explained elsewhere,

This is a poem with overtones of the Persian New Year, which falls on the Spring Equinox around March 21 and so coincides with the advent of spring.

Trees with white blooms like our magnolias or elderberries are being compared here to the miraculous white hand of Moses. Turning his hand white was one of his divine signs that God instructed the Hebrew prophet to use when he confronted Pharaoh:

Exodus 4:1,6-7

- “Then Moses answered, “But suppose they do not believe me or listen to me, but say, ‘The Lord did not appear to you.’… Again, the Lord said to him, “Put your hand inside your cloak.” He put his hand into his cloak; and when he took it out, his hand was leprous,[a] as white as snow. Then God said, “Put your hand back into your cloak”—-so he put his hand back into his cloak, and when he took it out, it was restored like the rest of his body—-”

This miracle is also mentioned in the Qur’an, and Persian poetry refers to it as a sign of renewal, since Moses can reverse the condition at will.

The other reference is to Jesus’ ability to raise the dead, as in Luke 7:11-14

- “11 Soon afterward he went to a town called Nain, and his disciples and a large crowd went with him. 12 As he approached the gate of the town, a man who had died was being carried out. He was his mother’s only son, and she was a widow, and with her was a large crowd from the town. 13 When the Lord saw her, he was moved with compassion for her and said to her, “Do not cry.” 14 Then he came forward and touched the bier, and the bearers stopped. And he said, “Young man, I say to you, rise!” 15 The dead man sat up and began to speak, and Jesus gave him to his mother. “

This poetry takes a dim view of people who put off achieving their hearts’ desires. It is very much a poetry of “seize the day.” It advises against letting yourself lose hope, and urges that you express life-fulfilling passion.”

“But still the Vine her ancient Ruby Yields:” Fitzgerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám 1:5

I continue with my proposed project of writing a commentary on the first edition of Edward FitzGerald’s translation of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám. FitzGerald was more faithful to the unconventional poetry attributed to Omar Khayyam than is generally thought, but there were moments in his first edition where he drew on images from other Persian poets, especially the Sufi mystic `Abd al-Rahman Jami (d. 1492) of Herat in what is now western Afghanistan. Britannica notes, “His most famous collection of poetry is a seven-part compendium entitled Haft Awrang (“The Seven Thrones,” or “Ursa Major”), which includes Salmān o-Absāl and Yūsof o-Zalīkhā.”

FitzGerald studied Jami with his friend (and likely man-crush) Edward Byles Cowell and produced a loose translation of the romance “Salaman and Absal.” Some of Quatrain 5 is drawn from the latter, as the great scholar A. J. Arberry pointed out (The Romance of the Rubáiyát, 195-196).

V.

Irám indeed is gone with all its Rose,

And Jamshýd’s Sev’n-ring’d Cup where no one knows;

But still the Vine her ancient Ruby yields,

And still a Garden by the Water blows.

The point of this verse is that wine and gardens — symbols of well-being and fulfillment — are eternal, whereas the glories of ancient kingdoms and kings are fleeting.

Arberry points out that there is a reference to Iram in Jami’s Seven Thrones and FitzGerald translated the lines of the Afghan poet as “Here Iram Garden seem’d in Secresy/ Blowing the Rosebud of its Revelation.”

In Chapter 89 of the Qur’an, 6-8, the question is asked, “Have you not seen how your Lord dealt with `Ad, Iram of the pillars, the like of which was never created in the land?”

This is a reference to Wadi Rum in what is now southern Jordan. Old Arabic inscriptions survive in Wadi Rum referring to it as Iram. The great epigraphist and archeologist Ahmad Al-Jallad at the Ohio University has discovered an Old Arabic inscription from 2,000 years ago mentioning the tribe of `Ad, which lived in Jordan. So the Qur’an was accurately reporting antiquities of a previous time. Trans-Jordan and the northern Hejaz had been ruled by the Arabic-speaking pagan Nabataean kingdom from circa 300 BCE until it was conquered by Rome in 106 CE. By the time of the Qur’an in the early 600s of the Christian era (CE), several old Nabataean cities, such as Hegra or Hijr and the settlements of Wadi Rum had declined and were no longer inhabited. The Qur’an blames this decline on Nabataean polytheism, since in its view only monotheism was a guarantee of a flourishing civilization.

But in the medieval period when the Khayyami poetry and then that of Jami was produced, Iram had become legendary, just a fabled ancient kingdom associated with the vanished `Ad people. FitzGerald thus used the image correctly to refer to a place that was once glorious but now fallen into ruins.

As for the Cup of Jamshid, it features in Zoroastrian mythology, which speaks of a line of ancient kings that included Jamshid. The “j” was pronounced “y” in ancient Persian, which was close to Sanskrit. So this figure was Yima, who also exists in Hindu mythology, as Yama, the god of death and the underworld. Indeed, he is described in the Vedas as the first man who died, and as a judge (dharmaraja), dressed in red finery.

Many figures in Hinduism also exist in Old Persian, but they often take on a different persona. In the ancient Iranian Book of Kings (Shahnameh), Yima or Jamshid is not a god but one of the first kings, whose kingdom at first flourishes epically but then goes into a tailspin. He had a magical chalice (jam) in which he could gaze and which would show him scenes from throughout the world.

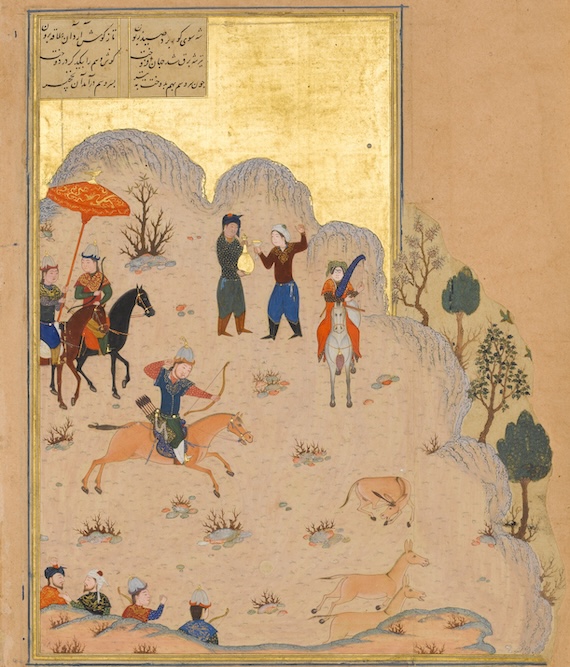

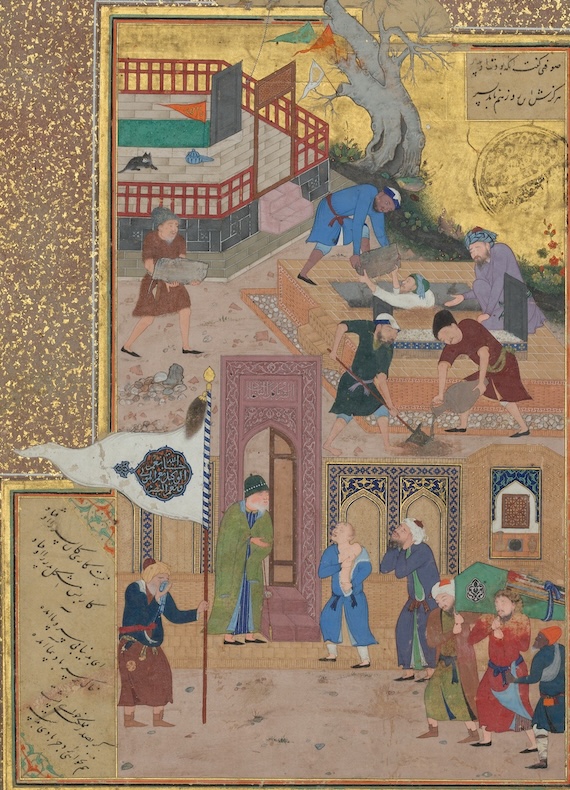

Detail. “Jamshid enthroned.” A miniature painting from a fifteenth century manuscript of the epic poem of Shahnama. Image taken from Shahnama. Originally produced in Iran, 1446. British Library.

References to the cup of Jamshid are everywhere in Persian poetry, so FitzGerald wouldn’t have had to read much of it to encounter them. They are certainly in Jami, whose Seven Thrones he studied with Cowell. Scholars have seen a resemblance of the cup of Jamshid to the Holy Grail of medieval European legend; my guess is that they both go back to a common Indo-European myth.

The final two lines may be drawn from the Bodleian manuscript of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám.

In my translation, no. 38 [39 of the Bodleian] has the line “Wine is molten rubies and the bottle is a deep, deep mine,” which bears a resemblance to “But still the Vine her ancient Ruby yields.”

The original is:

می لعل مذاب است و صراحی کان است

mai la`l-e mozab ast o surahi kan ast.

The last line, as Arberry says, could reflect Bodleian 147 (my 146):

“and walk with me among the flowers of the river bank”, which could be echoed by “And still a Garden by the Water blows.” “Flowers” in the original is bagh or garden.

بردار پیاله و سبو ای دلجو

برگَرْد به گِردِ باغ و لبِ جو؛

کاین چرخ بسی قَدِّ بُتانِ مَهْرو،

صد بار پیاله کرد و صد بار سبو

“Red Wine!” – the Nightingale cries to the Rose: FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám 1:6

The sixth quatrain of Edward FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám continues with its celebration of wine-drinking in the morning. It connects ancient Iran’s language of Middle Persian or Pahlavi, spoken in the Sasanian Empire 224–651 AD with the biblical figure of David, said in the Qur’an to be the author of the Psalms.

VI.

And David’s Lips are lock’t; but in divine

High piping Pehlevi, with “Wine! Wine! Wine!”

“Red Wine!” – the Nightingale cries to the Rose

That yellow Cheek of her’s’ to incarnadine.

FitzGerald may have been thinking of Psalm 104:15 here,

- and wine to gladden the human heart,

oil to make the face shine

and bread to strengthen the human heart.

(New Revised Standard Version Updated Edition)

Of course, David did not write the Psalms, and they are in Hebrew, not Middle Persian — though the Jews of Babylon interacted quite a lot with Middle Persian.

FitzGerald here subverted the Christian appropriation of David as a forefather of Jesus, and made him instead a forerunner of Omar Khayyam, possibly because of Psalms like the above. FitzGerald departed the Anglican church, I think around 1850, though he had long viewed himself as an “infidel” (and despaired of marrying the convinced Christian Elizabeth Charlesworth because of it). He was what we would now call gay or perhaps bisexual (Victorians did not have those categories), and joined a legion of secular atheist writers of the mid-Victorian period — Richard Monckton Milnes (his friend), Algernon Swinburne, George Meredith, Matthew Arnold and many others. The skepticism about conventional religion characteristic of the Persian poetry attributed to Omar Khayyam was one of its attractions for him.

“Red Wine!” – the Nightingale cries to the Rose

FitzGerald's Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám 1:6

A.J. Arberry proposed that in line 1, mentioning David, FitzGerald was drawing on a verse in the Calcutta manuscript of the Rubáiyát (C 92), which is reproduced at this site:

با باده نشین، که مُلْکِ محمود این است

وَزْ چنگ شنو، که لحنِ داوود این است؛

از آمده و رفته دگر یاد مکن

حالی خوش باش، زانکه مقصود این است

My (Juan’s) translation of this one is:

Sit with the wine, for this is Mahmud’s shore;

the harp is playing David’s melodies.

Recall this hectic to and fro no more–

be happy now: our purpose lies in this.

The transliteration is:

Bā bāde neshīn, ke molk-e Maḥmūd īn ast

va z chang shenow, ke laḥn-e Dāwūd īn ast;

az āmade o rafte digar yād makon

ḥālī khosh bāsh, z ān-ke maqsūd īn ast

Mahmud of Ghazni (r. 998 – 1030) ruled much of Central Asia, Afghanistan and north India. His court poet Manuchehri “praised wine as a source of resilience and celebration, especially during cultural festivals like Nowruz.”

The reference to David and the harp recalls the Muslim belief (shared by premodern Jews and Christians) that David authored and sang the Psalms.

The other three lines of 1:6 are drawn from the Bodleian manuscript number 67 (66 in my modern translation):

روزیست خوش و هوا نه گرماست و نه سرد

ابر از رخ گلزار همی شوید گرد

بلبل با زبان پهلوی با گل زرد

فریاد همی زند که می باید خورد

I translated it my own book in blank verse. A literal rendering would be

It’s a beautiful day, neither torrid nor freezing;

Rain clouds wash the face of the flower garden.

The nightingale speaks in the Pahlavi tongue to the yellow flower

crying out that it must drink wine.

The joke here is that a person with a sallow or yellowish complexion was thought in medieval Iran to be in need of some wine to give a healthier pink color to the cheeks. So a yellow tulip is being advised by the nightingale to imbibe for the sake of its health. One of the ways more secular-minded Muslims got around the (much-disregarded) prohibition on wine in strict Muslim law was to make an argument that Islam allowed medicine, and when wine was drunk for medicinal purposes it was all right. A sallow cheek could then be a pretext for some tippling.

One of my complaints about FitzGerald’s otherwise quite wonderful loose rendering is that he liked Latin words (Cambridge-educated gentlemen like FitzGerald could actually write poetry in Latin), and he used “incarnadine” to mean “redden.” The original Persian tends to avoid high falutin’ words and is usually direct and simple, an approach to which I tried to hew in my own, modern, poetic translation.

“The Bird is on the Wing”: FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám 1:7

Stanza 7 of the first edition of Edward FitzGerald’s translation of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám talks about how little time we have here on earth, and the urgency for us to enjoy life. “Repentance” is a luxury we can’t afford, the poetry affirms:

VII.

Come, fill the Cup, and in the Fire of Spring

The Winter Garment of Repentance fling:

The Bird of Time has but a little way

To fly — and Lo! the Bird is on the Wing.

This quatrain became especially famous and beloved. The perennially best-selling novelist James A. Michener took the title of one of his books from it and quoted it.

In my view, the first two lines resemble the Bodleian manuscript no. 61, which I translated:

Your love has trapped this aged head of mine;

if not, my hand would put this wine-glass down.

My mind repented but you tempted me;

time ripped the clothes that patience wove for me.

پیرانه سرم عشق تو در دام کشید

ورنه ز کجا دست من و جام نبید

آن توبه که عقل داد جانان بشکست

و آن جامه که صبر دوخت ایام درید

—-

Order Juan Cole’s contemporary poetic translation from

or Barnes and Noble.

or for $16 at Amazon Kindle

——-

I don’t know if it was in the Calcutta manuscript that Edward Cowell sent to FitzGerald from India in June 1857, but there is a quatrain attributed to Khayyam that shows up in such collections of his verse that could have suggested the last two lines of this poem:

افسوس که نامهٔ جوانی طی شد

وان تازه بهار زندگانی طی شد

آن مرغ طرب که نام او بود شباب

افسوس ندانم که کی آمد کی شد

I would translate this one this way in blank verse:

How sad — youth’s letter has been crumpled up,

and life’s fresh springtime waned and died away.

That warbling bird, the name of which was youth —

alas, I don’t know when it came or fled.

transliteration:

Afsūs ke nāmah-e javānī ṭayy shod

v-ān tāza bahār-e zendegānī ṭayy shod

ān morḡ-e ṭarab ke nām-e ū būd shabāb

afsūs nadānam ke kay āmad kay shod.

I give the transliteration so you can see the shape of the Persian words even if you don’t know the language. It is related to English and other Indo-European tongues. For instance, here javānī or youth is related to juvenile. Taza or fresh you may recognized from the “taza tea” in some tea shops. It comes to us from Hindi-Urdu, borrowed from Persian.

Edward Heron-Allen thought that the last two lines of 1:7 were drawn from a line of the great Sufi mystic Farid al-Din Attar (d. 1220), in his classic, Parliament of the Birds .

Arberry translates it, “The bird of Heaven’s sphere flutters on its path.”

Arberry (p. 197) also suggests that the first two lines were inspired by no. 447 of the Calcutta manuscript:

هر روز بر آنم که کنم شب توبه

از جام و پیاله لبالب توبه

اکنون که رسید وقت گل ترسم نیست

در موسم گل ز توبه یا رب توبه

A literal translation would be this;

Every day I determine to repent that night

Cup and chalice full to the brim– repentance!

Now that the time of the rose has arrived, I have no fear

In the season of the rose, from repentance, O Lord: repentance!

Transliteration:

Har rūz bar ānam ke konam shab tawba

az jām o piyāla lab-ā-lab tawba

aknun ke resīd vaqt-e gol tarsam nīst

dar mawsam-e gol ze tawba yā rabb tawba

The last verse cleverly has him repent of his repentance.

This quatrain is almost the same as one that appears in the Book of Choice of Attar, given at this site .

“Persian Starling, from the Song Birds of the World series,” Metropolitan Museum. Public domain.

In the first edition of the Encyclopedia of Islam , V. Minorsky explained that the Russian scholar Valentin Zhukhowsky (d. 1918) showed in the late nineteenth century that a high proportion of quatrains attributed to Omar Khayyam in the 1867 edition of Jean-Baptiste Nicolas (d. 1875) were also found in the collected works (divans) of 39 other poets. Some of them showed up in the works of several different authors. He called them the “wandering quatrains.”

The problem is not so much multiple attribution — that is common in medieval manuscripts. The problem is that there is no early stable corpus of poetry attributed to Omar Khayyam. You have a poem here and a poem there said to be his, but then another author will quote a few different and unrelated verses. And then many of these quatrains show up in the Collected Works or Divan of other poets. I have concluded that these are folk poems, written by many different people over time– some by artisans, some by courtiers, some by wandering dervishes, and some by women, and they were attributed to Khayyam as a “frame author.” The analogy is to The Arabian Nights, which were produced by anonymous story-tellers in Cairo, Baghdad and Aleppo over centuries and attributed to Scheherazade.

“A thousand Blossoms with the Day Woke:” FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám 1:8

Quatrain no. 8 in the first edition of Edward FitzGerald’s loose translation of the FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám is about the impermanence of all life — of flowers and of kings and heroes. It is a common theme in the Persian originals. I have argued that since some of this poetry grew up in the 1200s when Iran was ruled by Buddhist Mongols, there may be some Buddhist influence in the verses. One of the themes of Buddhism is the impermanence of all things. But of course this idea exists in Islam as well. Qur’an 55:26 says “Every being on earth is bound to perish.”

FitzGerald’s stanza is:

VIII.

And look — a thousand Blossoms with the Day

Woke — and a thousand scatter’d into Clay:

And this first Summer Month that brings the Rose

Shall take Jamshýd and Kaikobád away.

The mention of the fall of past kings with all their pomp is a reminder to live life to the fullest, since even the most opulent of lives is brief.

FitzGerald may also have liked the image of kings falling because he was a republican of sorts. During the failed continental revolutions of 1848, he wrote that he supported an Italian republic, and he later made clear that he was no fan of France’s Napoleon III. So the ephemerality of the kings may have had political implications for him. He was not a republican when it came to Britain, though, since he thought the monarchy had done well by the British people. He just held that no new dynasties should be established.

In his Romance of the Rubáiyát A. J. Arberry proposed that the first two lines here were taken from the first half of Calcutta quatrain 518 (also here ).

از آمدن بهار و از رفتن دی

اوراق وجود ما همی گردد طی

می خور! مخور اندوه که فرمود حکیم

غمهای جهان چو زهر و تریاقش می

I would translate it this way in blank verse:

Since spring has now arrived and winter’s gone,

the page of being is rolled up for us.

Drink wine! Drink in no grief, the sage has said:

The poison’s pain; the antidote is wine.

transliteration

az āmadan-e bahār o az raftan-e day

awrāq-e vujūd-e mā hamī gardad ṭayy

may khor! ma-khor andūh ke farmūd ḥakīm

ghamhā-yi jahān chū zahr o tiryāqash may

But there are other candidates for the inspiration for the first two lines here.

For instance, I translated no. 17 of the Bodleian manuscript as: “The spring breeze on a rose’s cheek spreads joy . . . No words about last winter can bring cheer.” (My no. 16).

بر چهرۀ گل نسیم نوروز خوش است

در صحن چمن روی دلافروز خوش است

از دی که گذشت هر چه گویی خوش نیست

خوش باش و ز دی مگو که امروز خوش است

—-

Arberry thought that the second two lines derived from the second half of Calcutta 497 (also here):

هنگام صبوح ای صنمِ فرخپی

برساز ترانهای و پیشآور می

کافکند به خاک صدهزاران جم و کِی

این آمدن تیر مَه و رفتن دی

My translation of this one would be as follows:

I hear my idol’s blessed dawn footfall:

“Strike up a song and bring for us some wine!”

A hundred thousand Jams and Kays are dust.

As April comes, December then departs.

transliteration:

hangām-e sabūḥ ay ṣanam-e farrokh-pay

barsāz tarāna’ī o pīsh-āwar may

k-afkand ba khāk sad-hazārān Jam o Kay

īn āmadan-i tīr-i mah o raftan-i day

(“Pay” is a classical Persian word for foot [now it is pa], akin to pod in our podiatry or the French pied and Spanish pie. “Sad” or a hundred is distantly related to our “century” or the French cent from which we get our word for a penny.)

This quatrain refers to the ancient Iranian custom of drinking a cup of wine in the morning, though here it is combined with a romantic scene where the protagonist hears his beloved’s auspicious footfalls as he wakes.

Jam here is short for Jamshid, another mythical ancient Iranian king. I explained about this figure here.

The verse uses almost mythological numbers (a hundred thousand) to describe the multitudes of past monarchs who are beneath the dust, to underline that no one is immune to the swift and deadly march of time (and therefore, we may as well enjoy ourselves while we are here).

“Plate with king hunting rams. Sasanian. Date: ca. mid-5th–mid-6th century CE. Iran, said at the time of the acquisition to have been found in Qazvin. Medium: Silver, mercury gilding, niello inlay. Metropolitan Museum, NYC.

Kay here is short for Kaykobad, as FitzGerald recognized. Kay Kobad or Kay Kawad is a mythical ancient Iranian king — indeed, the old Zoroastrian sources make him the first king, sort of like Saul was said to be the first king of ancient Israel.

Abo’l-Qasem Ferdowsi (d. 1025), the author of the great Persian epic, the Book of Kings (Shahnameh), told a story that the hero Zal was dissatisfied with the candidates for kingship. A pious priest (mowbed) suggested that he seek out Kaykobad. So Zal sent his son, the great warrior Rostam, to discover him in Alborz mountains near today’s Tehran. He was found living along a river bank.

Julius von Mohl, born in Stuttgart, moved to Paris and became a major specialist in Near Eastern studies, being appointed to the first chair of Persian at the Collège de France in 1847. He was commissioned by the French government to translate Ferdowsi’s Book of Kings.

German-British translator Helen Zimmern in 1883 brought out a prose translation of von Mohl’s French version of Ferdowsi. She told the story of Rustam’s quest for Kaykobad this way:

- “But Zal, when he had drawn up his army in battle array, spake unto them, saying-

“O men valiant in fight, we are great in number, but there is wanting to us a chief, for we are without the counsels of a Shah [king], and verily no labour succeedeth when the head is lacking. But rejoice, and be not downcast in your hearts, for a Mubid hath revealed unto me that there yet liveth one of the race of Feridoun to whom pertaineth the throne, and that he is a youth wise and brave.”

And when he had thus spoken, he turned him to Rustem and said-

“I charge thee, O my son, depart in haste for the Mount Alberz, neither tarry by the way. And wend thee unto Kai Kobad, and say unto him that his army awaiteth him, and that the throne of the Kaianides is empty.”

And Rustem, when he had heard his father’s command, touched with his eyelashes the ground before his feet, and straightway departed. In his hand he bare a mace of might, and under him was Rakush the swift of foot. And he rode till he came within sight of the Mount Alberz, whereon had stood the cradle of his father. Then he beheld at its foot a house beauteous like unto that of a king. And around it was spread a garden whence came the sounds of running waters, and trees of tall stature uprose therein, and under their shade, by a gurgling rill, there stood a throne, and a youth, fair like to the moon, was seated thereon. And round about him leaned knights girt with red sashes of power, and you would have said it was a paradise for perfume and beauty.

Now when those within the garden beheld the son of Zal ride by, they came out unto him and said-

“O Pehliva, it behoveth us not to let thee go farther before thou hast permitted us to greet thee as our guest. We pray thee, therefore, descend from off thy horse and drink the cup of friendship in our house.”

But Rustem said, “Not so, I thank you, but suffer that I may pass unto the mountain with an errand that brooketh no delay. For the borders of Iran are encircled by the enemy, and the throne is empty of a king. Wherefore I may not stay to taste of wine.”

Then they answered him, “If thou goest unto the mount, tell us, we pray thee, thy mission, for unto us is it given to guard its sides.”

And Rustem replied, “I seek there a king of the seed of Feridoun, who cleansed the world of the abominations of Zohak, a youth who reareth high his head. I pray ye, therefore, if ye know aught of Kai Kobad, that ye give me tidings where I may find him.”

Then the youth that sat upon the throne opened his mouth and said, “Kai Kobad is known unto me, and if thou wilt enter this garden and rejoice my soul with thy presence I will give thee tidings concerning him.”

When Rustem heard these words he sprang from off his horse and came within the gates. And the youth took his hand and led him unto the steps of the throne. Then he mounted it yet again, and when he had filled a cup with wine, he pledged the guest within his gates. Then he gave a cup unto Rustem, and questioned him wherefore he sought for Kai Kobad, and at whose desire he was come forth to find him. And Rustem told him of the Mubids, and how that his father had sent him with all speed to pray the young King that he would be their Shah, and lead the host against the enemies of Iran. Then the youth, when he had listened to an end, smiled and said-

“O Pehliva, behold me, for verily I am Kai Kobad of the race of Feridoun!”

And Rustem, when he had heard these words, fell on the ground before his feet, and saluted him Shah. Then the King raised him, and commanded that the slaves should give him yet another cup of wine, and he bore it to his lips in honour of Rustem, the son of Zal, the son of Saum, the son of Neriman. And they gave a cup also unto Rustem, and he cried-

“May the Shah live for ever!”

Then instruments of music rent the air, and joy spread over all the assembly . . .”

“But come with old Khayyam and leave the Lot,” FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám 1:9

As with stanza 1:8, the next quatrain in Edward FitzGerald’s 1859 translation of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám concerns the fleeting character of political glory, and of life in general. It continues to introduce English-speaking audiences to Iranian kings and heroes, the Persian equivalents of Agamemnon and Achilles:

IX.

But come with old Khayyam, and leave the Lot

Of Kaikobád and Kaikhosrú forgot:

Let Rustum lay about him as he will,

Or Hátim Tai cry Supper — heed them not.

Discussion:

I spoke about the mythical first Iranian king, Kay Kobad here.

Arberry notes that Kaykhosrow is referred to in 139 of the Bodleian manuscript. He is Khosrow II (d. 628), the Sasanian Iranian monarch who ruled much of the known world and took the Middle East away from the Eastern Roman Empire.

Hatim Tayy was held to be among the three most generous men of pre-Islamic Arabia in the 500s AD, a chieftain and poet. Many stories are told about his amazing generosity, even to enemies. But the quatrains attributed to Khayyam warn that you should never let yourself become obligated to anyone, even such a generous person as Hatim. You should retain your individuality and freedom of action, rejecting the constraints of society.

Rustam is Iran’s national hero, the great mythical warrior of ancient times, akin to Hercules for Romans and Greeks or Conan for the Irish. One of the great tragedies of his life is that he sired a son, Sohrab, but left his mother, and the boy grew up to face him on the battlefield. Rustam, without knowing he was fighting his own son, kills Sohrab.

This story was told by the Victorian poet Matthew Arnold just a few years before FitzGerald translated the Rubáiyát and may have been on FitzGerald’s mind for that reason, apart from the Rustam stories he found in the Persian poetry he studied with Hockley and Cowell.

Arnold has Rustam’s army fear Sohrab and say,

- “O Rustum, like thy might is this young man’s!

He has the wild stag’s foot, the lion’s heart;

And he is young, and Iran’s chiefs are old,

Or else too weak; and all eyes turn to thee.

Come down and help us, Rustum, or we lose!”

FitzGerald’s generation of English-speakers were discovering the beauties of Persian poetry and the attractions of myth and legends of Iran. A lot of the impetus for this interest in Persian came from the British Empire in India, which supplanted the Mughals and other powers in the subcontinent.

—-

Order Juan Cole’s contemporary poetic translation of the Rubáiyát from

or Barnes and Noble.

or for $16 at Amazon Kindle

——-

Many Indian polities were ruled by Muslims at that time, even though they were only 10 percent of the population. Central Asian Muslims had heavy horse cavalry and they were early adopters of canon and muskets, and so could conquer Indian villagers. Muslim states in India used Persian as their chancery language, for government and administration, as well as diplomacy. So Indians, including many Hindus, cultivated Persian, sort of the way a lot of Europeans cultivated French in the 18th and 19th centuries. Persian was the language of the Iranian plateau, but it was also the language of educated people throughout what we would call the Middle East and Central and South Asia, and its medieval poetry was widely studied.

As the British East India Company gradually subdued India from 1757 forward, it trained some of its personnel in Persian. Some of them became interested in literature, publishing on it back in Britain, or translating books of poetry or history. It was part of the process whereby Britain learned about India so as to rule it. FitzGerald knew retired East India Company officials such as Major Hockley, who lived nearby in Ipswich, and with whom he studied Persian. FitzGerald, from a wealthy Anglo-Irish family, disapproved of the British Empire and was largely uninterested in politics, but he caught the Persian bug from other fans, especially his young friend Edward Cowell. They thought at least some of the poetry lovely, using phrases like “fine and just.”

The poetry they began to adore was not for the most part produced in India, though the latter had great Persian poets. They learned from Indian scholars to value classical Persian literature, that of Saadi, Hafez, Rumi, Attar, Ferdowsi and Jami. Some of that poetry was about ancient kings and heroes, or used their stories to make a point.

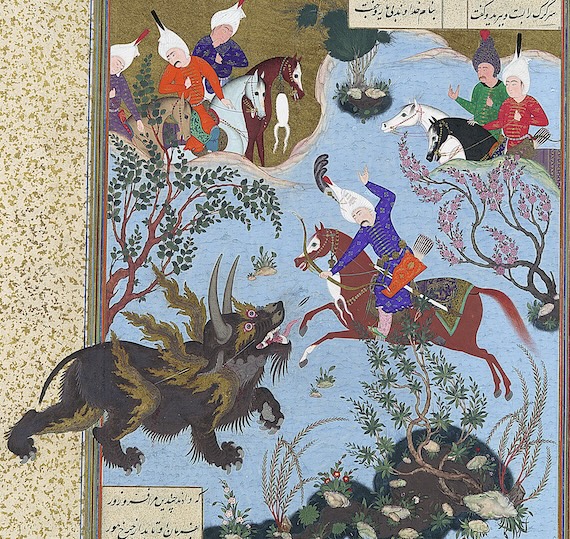

Detail, “The Combat of Rustam and Ashkabus”, Folio 268v from the Shahnama (Book of Kings) of Safavid monarch Shah Tahmasp (r. 1524 to 1576). By the author Abu’l Qasim Firdausi. Iranian Painting attributed to Mirza Muhammad Qabahat; Workshop director ‘Abd al-‘Aziz. ca. 1525–30, Tabriz. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

A. J. Arberry held that the first two lines of stanza 9 derived from no. 60 in the Calcutta manuscript of the Rubáiyát, which is also here. I translate it this way:

One gulp of wine outshines the kingdom of Ka’us–

it’s better than Qobad’s throne or the realm of Tus.

A tipsy rascal’s every groan as night abates

is better than obeying two-faced celibates.

یک جرعهٔ می ز ملک کاووس به است

از تخت قباد و ملکت طوس به است

هر ناله که رندی به سحرگاه زند

از طاعت زاهدان سالوس به است

FitzGerald may have seen a resemblance between this quatrain and some passage in a poem by Hafez of Shiraz (1325–1390), since he wrote “Hafez” next to Calcutta 60 on the manuscript.

The second two lines were inspired by the last half of Calcutta no. 519. That poem is also here . This is my fairly literal translation:

As long as you have bones, blood, and sinews,

do not set foot outside the house of fate.

And bend your neck to none, even Rustam;

Take on no burdens, even Hatim Tayy.

تا در تن تست استخوان و رگ و پی،

از خانهٔ تقدیر منه بیرون پی

گردن منه؛ ار خصم بود رستم زال

منت مکش؛ ار دوست بود حاتم طی.

“With me along some Strip of Herbage Strown:” Edward FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám 1:10

The tenth quatrain in the first edition of Edward FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám continues the theme of the irrelevance of political power to happiness, which lies instead in love. The Persian originals make clear the meaning here, which is a little cryptic in FitzGerald’s rendering.

X.

With me along some Strip of Herbage strown

That just divides the desert from the sown,

Where name of Slave and Sultán scarce is known,

And pity Sultan Mahmud on his Throne.

The previous stanza asked the reader to “leave” the ancient Iranian kings and heroes, and to “heed them not.” Here, we “pity” Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni on his throne because he does not have the lover that Khayyam has, whom he has to sneak out to meet beyond the cultivated land of the village where no one will see them.

A. J. Arberry (Romance of the Rubáiyát, 199) points out that the phrase “Strip of Herbage” is obviously a translation of the Persian “Lab-i kisht,” the “edge of cultivated land.” FitzGerald in his notes says that he saw it a lot in the poetry.

This phrase occurs in the first two lines of the Bodleian manuscript no. 25 (my 24):

در فصل بهار اگر بتی حور سرشت

پر می قدحی دهد مرا بر لب کشت

I translated it non-literally as

“If an earthly angel offered me a cup of wine

as we two sat along the river bank in spring . . .”

transliteration:

dar fasl-e bahār agar botī hūr-seresht

por mey qadahi dahad marā bar lab-e kesht

“Lab” in Persian is lip and is a cognate with the English word. In linguistics, “labial” means “uttered with the participation of one or both lips.”

“Kesht” or cultivated land in Persian is a cognate with the Latin cultura and the origin of our English word culture.

The image here is sneaking off to the dividing line between inhabited and wild spaces, where the lovers won’t be seen. This imagery would have resonated with Americans in the age of the western frontier. I figured in our contemporary urban civilization, more people have experience with a land/ water demarcation between inhabited spaces and nature, so I set the picnic on a riverbank.

My phrase “earthly angel” condenses references in the original to “bot” and “hur” or houri. bot, pronounced boat, in Persian means “idol,” as in pagan idol, and derives from the Sanskrit Buddha, since the Iranian Muslims encountered Buddhist temples as they conquered Khorasan, Afghanistan and what is now Pakistan. Poets took it up in exactly the way our Hollywood did, as a sex symbol — an “idol” was a beautiful beloved.

Merriam-Webster defines houri as “1: one of the beautiful maidens that in Muslim belief live with the blessed in paradise. 2: a voluptuously beautiful young woman.” Going into all that would be an essay in itself. Just to say that the Persian poets often used definition no. 2 here.

Hence my “earthly angel.”

Edward Heron-Allen suggested that the second two lines come from second two lines of a poem in the Bodleian manuscript, no. 155 (my 154):

و آنکه من و تو نشسته در ویرانی

عیشی بود آن، نه حد هر سلطانی

This poem talks about two lovers planning a picnic, saying if we could get hold of a loaf of bread, some lamb kebabs and some wine,

“and we were snuggling in the wilderness–

we’d put to shame the pomp of any court.”

transliteration:

va ān keh man o to neshesteh dar virānī

ʿīshī bovad ān, na ḥadd-e har solṭānī

So that is why Mahmud is to be pitied — his magnificent court cannot measure up to the simple pleasures of a humble meal eaten by two lovers who can then snuggle with one another, away from prying eyes.

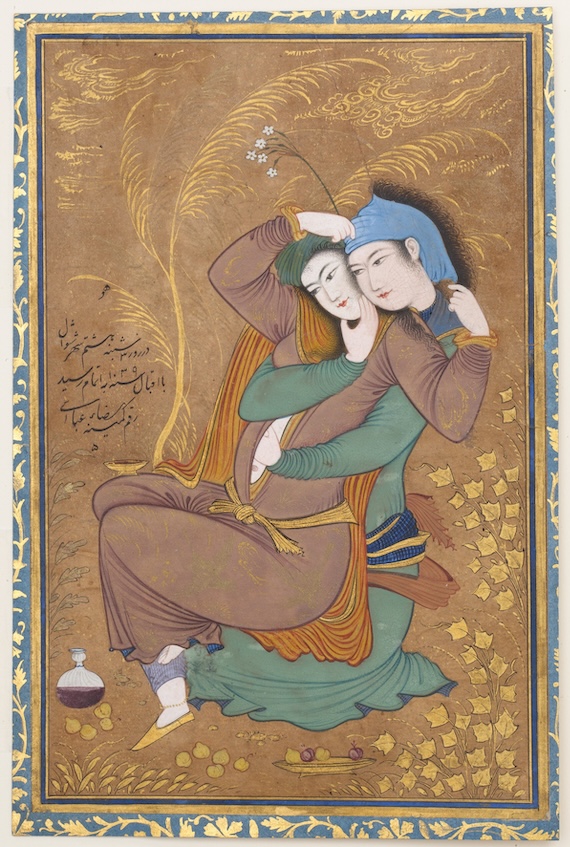

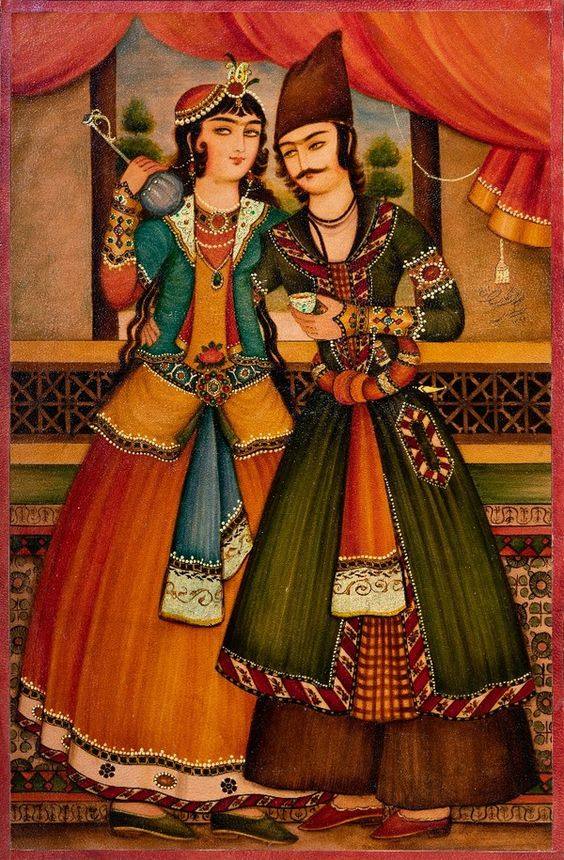

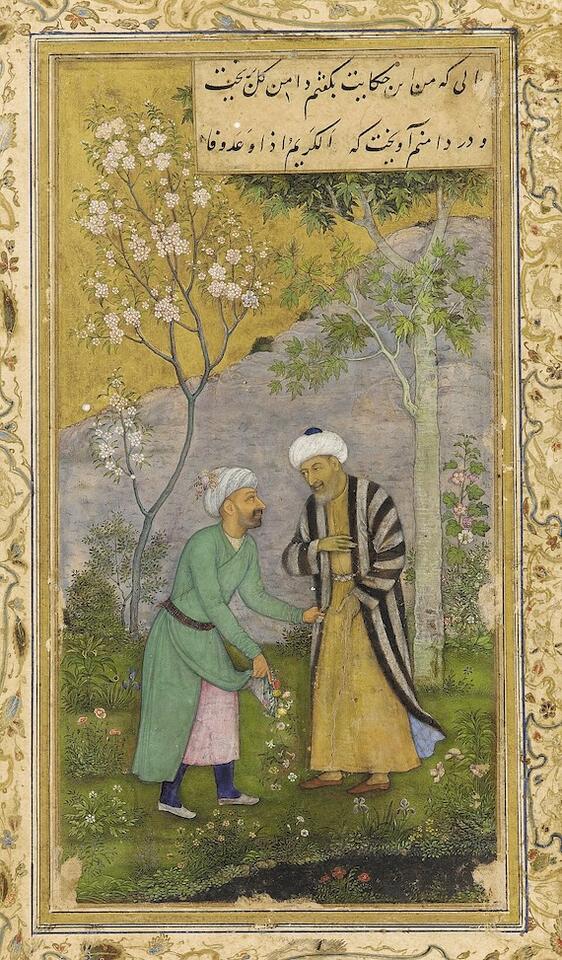

“The Lovers,” by Riza-yi ‘Abbasi (Iranian, ca. 1565–d. 1635), dated 1039 AH/ 1630 CE, Isfahan. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Mahmud is not mentioned by name in these particular originals, but he was an epic figure in Persian poetry whom FitzGerald would have met with in his reading in this literature, including no. 92 of the Calcutta manuscript of the Rubaiyat, as I discussed here.

“A Flask of Wine, a Book of Verse, and Thou:” Edward FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám 1:11

The eleventh quatrain in the first edition Edward FitzGerald’s translation of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám became one of the more famed poems in the English language. It epitomized romance for people in the late 19th and through the 20 century. Nervous young men brought it along on dates to read out as an ice breaker, especially as the rise of the automobile allowed a culture of dating — since couples could escape their parents’ houses and the watchful eyes of townspeople. I found one notice that a dentist in Britain gave the Rubáiyát to a woman patient, and her husband sued the dentist for attempted alienation of affection.

XI.

- Here with a Loaf of Bread beneath the Bough,

A Flask of Wine, a Book of Verse, and Thou

Beside me singing in the Wilderness —

And Wilderness is Paradise enow.

FitzGerald later revised it to its most renowned version:

- A book of Verses underneath the Bough,

A Jug of Wine, a Loaf of Bread — and Thou

Beside me singing in the Wilderness–

Oh, Wilderness were Paradise enow!

This stanza is entirely based on no. 149 of the Bodleian manuscript.

تُنْگی میِ لَعْل خواهم و دیوانی،

سَدِّ رَمَقی باید و نصف نانی،

وانگه من و تو نشسته در ویرانی،

خوشتر بُوَد آن ز مُلْکَتِ سلطانی

I translated it into contemporary American English, staying closer to the original, as no. 148 in my rendering of the entire Bodleian Ms.:

- A book of poetry, some ruby wine, and you,

and half a loaf of bread — I don’t need any more;

when you and I are curled up in the great outdoors,

our bliss outshines the glories of an emperor.

Transliteration:

tongi-ye may-e laʿl khᵛāham o divānī,

sadd-e ramqī bāyad o nesf-e nānī,

vāngah man o to neshaste dar vīrānī,

khosh-tar bovad ān ze molkat-e soltānī.

The word that FitzGerald translated as “wilderness” (vīrānī) has the connotations of “ruin, desolation.” It is being contrasted to the opulent monarch’s golden court. Some bread, wine and poetry enjoyed by lovers away from the town, where fields turn to desert, the poem is saying, are superior in the happiness they bestow to the pomp and circumstance of palaces.

FitzGerald cleverly altered this contrast between humble surroundings and the royal court to one between earthly simplicity and visions of the afterlife. Here he was true to the unconventional quatrains attributed to Khayyam, which often prefer the actual pleasures of this world to what its authors viewed as the imaginary delights of paradise.

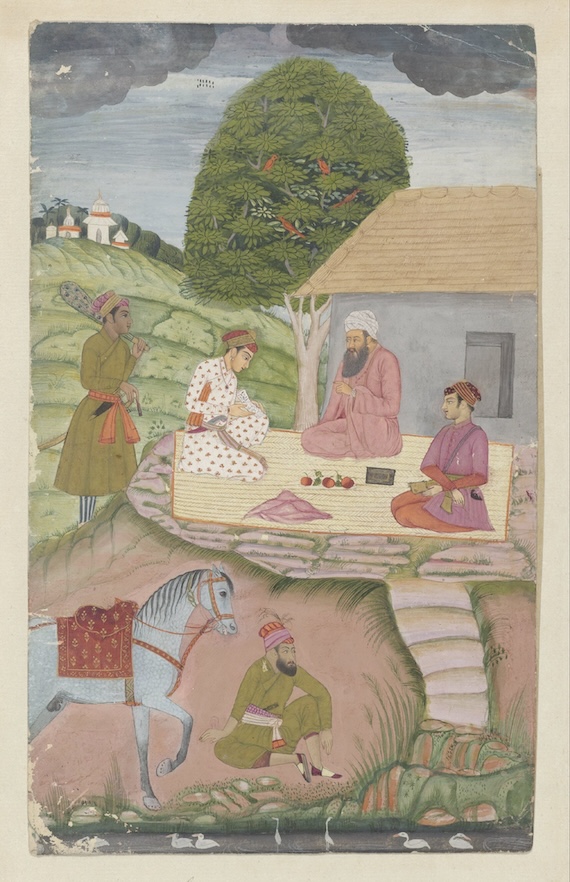

The miniature painters of Iran and Mughal India often showed lovers sneaking off to secluded gardens or woods (underneath a bough!), even though in medieval Iran and India gender segregation was the norm and dating was a death sentence if it became known– marriages were arranged. If one believes the poets and painters, though, the strict norms of society were at least sometimes successfully flaunted.

“The Lovers,” c. 1630–40 Persia (Iran). Ink, colors, and gold on paper. [Likely Safavid Isfahan.] Minneapolis Institute of Art.

The lesbian lovers Katherine Harris Bradley and Edith Emma Cooper, who wrote as “Michael Field,” took “Underneath the Bough” as the title for their 1893 volume of verse.

The phrase “Ah Wilderness,” which is how playwright Eugene O’Neill remembered the line, became the title of his play, set in 1906 at the height of the Omar craze in America, where it becomes an element in the adolescent rebellion of the protagonist. In 1935 it was made into a movie starring Wallace Beery, Lionel Barrymore, and Aline MacMahon. O’Neill was one of three writers of the script, and Metro Goldwyn Mayer paid more for the play script than any studio ever had before.

FitzGerald’s translation now seems old-fashioned, with its archaic use of “enow” for “enough.” Victorian poets often hearkened back to the medieval, as with Alfred Tennyson on Elaine and Lancelot in “Idylls of the King:”

- . . . ‘So be it,’ cried Elaine,

And lifted her fair face and moved away:

But he pursued her, calling, ‘Stay a little!

One golden minute’s grace! he wore your sleeve:

Would he break faith with one I may not name?

Must our true man change like a leaf at last?

Nay–like enow: why then, far be it from me

To cross our mighty Lancelot in his loves!

In their youths, FitzGerald and Tennyson were close friends, and FitzGerald played a role in Tennyson’s career, at one point supporting him financially. He arranged for a second edition of Tennyson’s second volume of poetry. Tennyson’s third outing, “In Memoriam,” caught Queen Victoria’s eye and she made him Poet Laureate.

“Take the Cash in Hand:” Edward FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám 1:12

Quatrain no. 12 in the first edition of Edward FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám concerns the imperative to live in the moment and take our pleasures where we can, disregarding visions of future power or the afterlife, which we may never achieve.

XII.

“How sweet is mortal Sovranty!”-think some:

Others” How blest the Paradise to come!”

Ah, take the Cash in hand and wave the Rest;

Oh, the brave Music of a distant Drum!

This translation is based on no. 34 in the Bodleian manuscript, also found here.

گویند بهشتِ عَدْن با حور خوش است،

من میگویم که: آب انگور خوش است

این نقد بگیر و دست از آن نسیه بدار،

کاواز دُهُل برادر از دور خوش است.

I translated it as poetry in my own rendering of the Rubáiyát. Literally, the original has:

They say that the Garden of Eden with houris is delightful;

I say that the elixir of the grape is delightful.

Take the cash on the barrel head and don’t seek out a loan–

Since, brother, drumming is only pleasant when heard from afar.

transliteration:

gūyand behesht-e ʿadn bā ḥūr khosh ast,

man mīgūyam ke: āb-e angūr khosh ast.

īn naqd begīr o dast az ān nasīa bedār,

k-āvāz-e dohol barādar az dūr khosh ast.

—-

Order Juan Cole’s contemporary poetic translation of the Rubáiyát from

or Barnes and Noble.

or for $16 at Amazon Kindle

——

The Persian original does not mention ambition for power or sovereignty, but we have seen that it is deprecated in some of the verses already translated by FitzGerald, so as usual he is “mashing” more than one poem’s emphases together.

The first two hemistiches contrast the present pleasure of settling down with a fine vintage of wine to the pleasures promised in the Qur’an in paradise. So this stanza is quite blasphemous.

In Muslim imagery, the garden of Eden is not only the mythical setting of the first advent of humans, but is also the name of the heaven of the afterlife. The Qur’an, produced in the early 600s AD in arid Arabia, envisions paradise as lush and green, with shade and fruit trees, and with streams running through it. These elements are celebrated in Islamic art, as Emma Clark has discussed. She points that the only word mentioned as being spoken in the Islamic heaven is “Peace.” The houris are heavenly companions, described in erotic terms. They likely come from Zoroastrian lore, where the soul-force was thought to be a daena, in the form of an ethereal heavenly woman, which are made visible for believers in paradise.

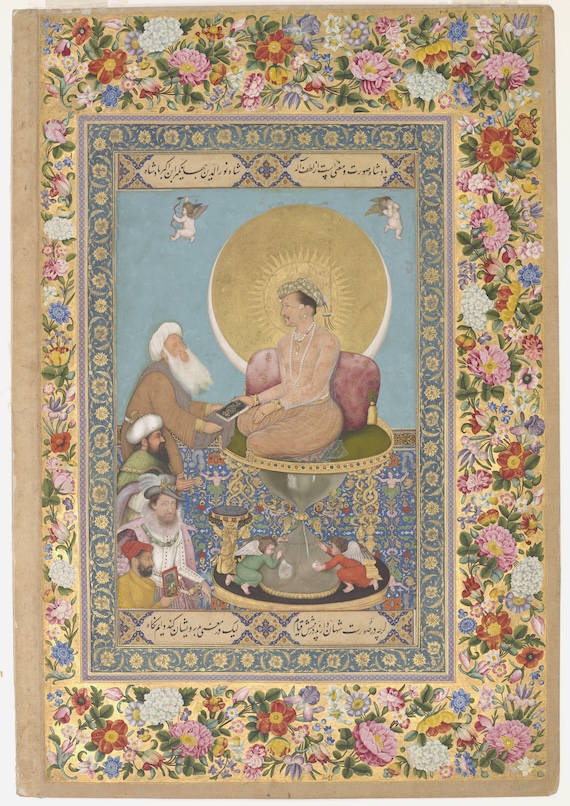

Islamic garden at the palace complex in Granada meant to evoke the Qur’an’s image of paradise. 2010. © Juan Cole.

One of the words for paradise in the Muslim scripture is firdaws, a loan from Persian pairidaeza, “around a wall,” that is, a walled enclosure or garden. Pairidaeza also came into Greek from Iran, as paradeisos, originally meaning a park. It was used in the Greek Bible for heaven, and it then was taken into English as paradise. So the Qur’an’s firdaws and the English paradise are descendants of the same Old Persian word meaning enclosed garden or orchard.

Here, the word used is the Persian behesht. “Beh” in Persian means “good.” The Good Place is also a phrase we use in English

Enjoying the pleasures of life immediately in this verse is compared to spending cash rather than dealing with money in the form of a loan, which involved delayed gratification. Likewise, the Persian line cleverly points out that all the talk of the next life sounds appealing when the prospect is far off, but maybe not so much as the reality nears, just as drumming is better appreciated from a distance.

These unconventional Persian quatrains openly question the afterlife and even the existence of God, which made them appealing to British Radicals like FitzGerald and then the Pre-Raphaelites, who were pioneering new forms of secularity and unbelief in Victorian Britain. They saw in this poetry a kindred endeavor and promoted it widely. They were impelled to unbelief by the new findings of science about geology and the dinosaurs, which disproved the Bible’s short chronology of 6,000 years for the age of the earth, and by their interest in unconventional forms of sexuality — whether queerness or polyamory. Here too the Rubáiyát corpus expressed similar ideas along with its skeptical approach to religion.

“Look to the Rose:” Edward FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám 1:13

Stanza no. 13 of the first edition of Edward FitzGerald’s translation of The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám is about the free gifts we receive from nature.

XIII.

- Look to the Rose that blows about us — “Lo,

“Laughing,” she says, “into the World I blow:

“At once the silken Tassel of my Purse

“Tear, and its Treasure on the Garden throw.”

A. J. Arberry wrote that it is based on poem no. 398 in the Calcutta manuscript, which can now be found here:

گل گفت که دست زرفشان آوردم

خندان خندان سر به جهان آوردم

بند از سرِ کیسه برگرفتم رفتم

هر نقد که بود در میان آوردم

I translate it this way in blank verse:

The rose proclaimed, “My hand cast forth the gold;

I blossomed, laughing, up into the world.

I have untied my purse and emptied out

the cash that was inside into your midst.

Transliteration:

gol goft ke dast-e zar-fishān āvardam,

khandān khandān sar be jahān āvardam.

band az sar-e kīsa bar-gereftam raftam,

har naqd ke būd dar miyān āvardam.

Arberry says FitzGerald wrote in the margin of this poem, “very pretty.” As a secular man who owned vast estates, he loved nature and liked sometimes to get his hands dirty in soil, so he appreciated the lesson here, that nature bestows its priceless gifts on us unasked.

Iranian poets often praised the generosity of nature. As Aisha Abdelhamid observed, Rumi wrote,

- “Be like the sun for grace and mercy.

Be like the night to cover others’ faults.

Be like running water for generosity.

Be like death for rage and anger.

Be like the Earth for modesty.

Appear as you are.

Be as you appear.”

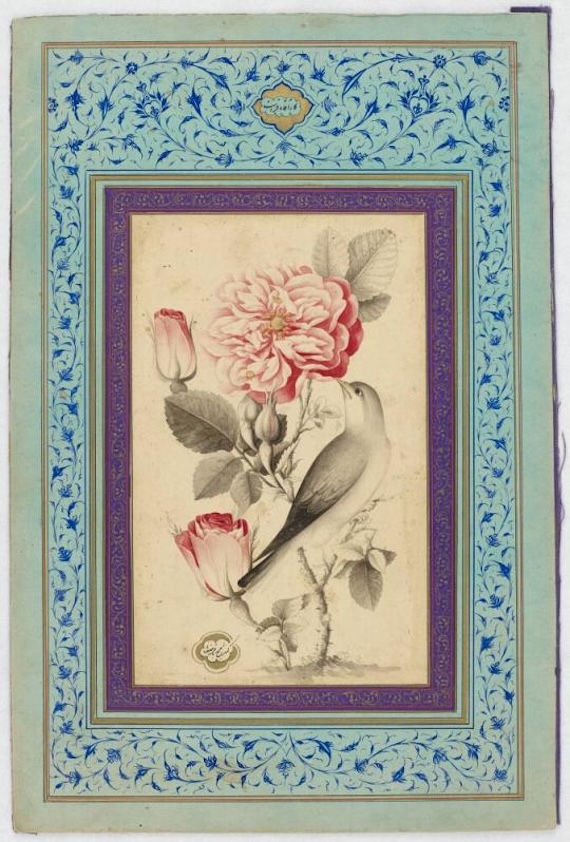

As for the rose, it is a symbol for a lot of things in Persian poetry, including boundless and unexpected generosity.

Hushang A`lam explains in the Encyclopaedia Iranica that Hafez of Shiraz (d. 1390) called the rose “the king of beauty,”

and he identifies four basic contexts in which it appears in Persian poetry.

1. It is a symbol and a feature of spring, and thus of renewal. Moḥammad-Taqi Bahār (d. 1950) wrote, “The new spring arrived, and the red rose laughed.” A`lam explains that for the rose to “laugh” means that it opened out.

2. Roses are also contrasted to thorns, so that Saadi (d. 1291) in the Golestan [Rose-Garden] says, “Wherever there is a rose, there are thorns.” A`lam writes, “This contrast between the rose, symbolizing beauty and smoothness, and thorn as a symbol of harshness has often been utilized by poets to convey the general idea that success in attaining one’s goal is usually concomitant with hardship, or that pleasures are often marred by annoyances such as thorns scratching the hand wishing to pluck a rose.”

3. Roses frequently appear as the beloved of the nightingale, symbolizing passionate and even obsessive love. For mystics, this is the unquenchable thirst of the soul (the nightingale) for God (the rose).

4. The rose can also refer to the beloved’s face, so that pink cheeks are compared to the rose. A beloved is “rose-faced” or gol-rokh.

“Roses and Nightingale,” by Muhammad Baqir (Persian, active 1740s–1800s), Ink and watercolor on paper, gift of Nasrin and Abolala Soudavar, Object number 2015.97, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

An example is the beginning of a ghazal or ode of Hafez, no. 25:

The red rose blossomed and the nightingale fell drunk;

You Sufis who love wine, the call to joy is heard!

—-

“Like Snow upon the Desert’s dusty Face:” FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám 1:14

Quatrain 14 emphasizes how short life is, even with all the good things the earth offers us (of which we should take advantage while we can).

XIV.

- The Worldly Hope men set their Hearts upon

Turns Ashes — or it prospers; and anon,

Like Snow upon the Desert’s dusty Face

Lightning a little Hour or two — is gone.

“Lightning” here is is a typographical error for “Lighting,” which FitzGerald corrected in subsequent editions.

Arberry identifies the original, to which FitzGerald has been fairly faithful, as no. 271 in the Calcutta manuscript. This quatrain does not appear to have been reprinted on the internet until now. He edited it slightly:

ای دل همه اسباب جهان ساخته گیر

دنیا همه سر بسر ترا خواسته گیر

وانگاه برویی آن چو در صحرا برف

روزی دو سه بنشسته و بر خاسته گیر

My literal blank verse version of this one is as follows:

Dear heart, accept the world with its trappings

The whole wide world is yours if you want it;

but you will sit on it, like desert snow,

for two or three days, and then you’ll be gone.

“Desert” here is ṣaḥrā, borrowed from Arabic, which also came into English as a proper noun — as the name of the world’s largest desert, the Sahara.

Dew is more often used as a symbol of impermanence in classical Persian poetry than snow, though we do find some other instances of it. In his Diwan of Shams-e Tabriz, the great mystic Jalal al-Din Rumi says,

مانند برف آمد دلم، هر لحظه میکاهد دلم

My heart came like snow; every moment it diminishes, my heart.

In his spiritual philosophy putting away ego and carnal desires is the path to union with the divine, and he compares this dwindling away of the self to melting snow. The heart, or self, wants to merge with the divine, in his philosophy.

That spiritual use of the image of snow is very different from this stanza attributed to Khayyam, since it is secular-minded and gloomy and doesn’t believe in an afterlife, or probably even God.

Snow also shows up as an obstacle to warriors fighting, in the epic of Abo’l-Qasem Ferdowsi, the Shahnameh or Book of Kings. I know a lot of outsiders may not associate Iran with snow, but it can snow heavily in the north of the country. I remember in the early 70s when a heavy snowfall in Tehran caused the roof of the airport to collapse. And there are ski slopes near Tehran.

One of the ancient heroes whose tale is told by Ferdowsi is Isfandiyar, a crown prince whose armor and diamond arrow-heads make him all but invincible. He was a great supporter of the Persian prophet Zarathrustra (whom the Greeks called Zoroaster) and his religion, which was the religion of most of Iran, Iraq and parts of what is now Central Asia and Pakistan in ancient times. Isfandiyar fought many battles against supernatural creatures and other heroes but met a tragic end, like Achilles, because there was one place on his body he was vulnerable.

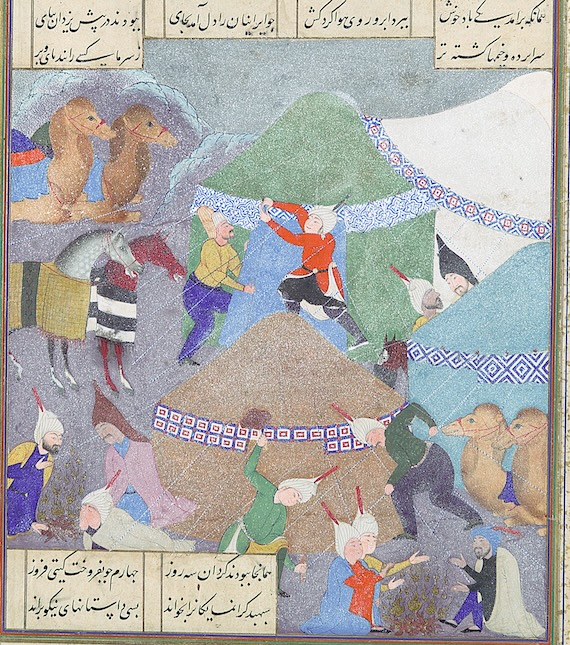

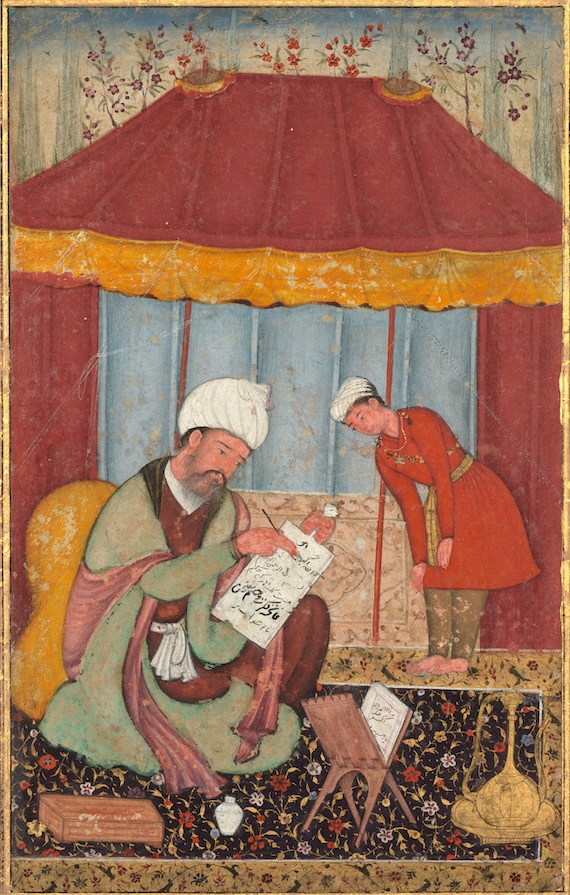

Detail. “Isfandiyar’s Sixth Course: He Comes Through the Snow”, Folio 438r from the Shahnama (Book of Kings) of Shah Tahmasp; Author Abu’l Qasim Firdausi; Iranian Painting attributed to ‘Abd al-Vahhab, ca. 1525–30: Opaque watercolor, ink, silver, and gold on paper Metropolitan Museum. Public Domain.

The Met explains, “After three days and nights of ceaseless snow and terrible cold, everyone in Isfandiyar’s army turned to prayer. Instantly the clouds blew away, and they gave thanks to God. Here, Isfandiyar’s followers prepare for the storm, warming themselves beside campfires and securing their tents. Most scenes in the Shahnama have no reference to weather. Either the sun shines or the stars twinkle in the sky. Here, however, the artist successfully conveys the sense of the beginning of a heavy snowfall against a gray sky.”

So here is another meaning of snow in Persian poetry: an obstacle in life’s warfare.

—

“And those who husbanded the Golden Grain:” FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám 1:15

Stanza 15 of the first edition of Edward FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám has for its theme a denial of the afterlife and resurrection.

XV.

And those who husbanded the Golden Grain,

And those who flung it to the Winds like Rain,

Alike to no such aureate Earth are turn’d

As, buried once, Men want dug up again.

This stanza is based on no. 68 in the Bodleian manuscript:

زآن پیش که بر سرت شبیخون آرند

فرمای که تا بادهٔ گلگون آرند

تو زر نهای ای غافل نادان که تو را

در خاک نهند و باز بیرون آرند

The original is not set on a grain farm, but begins with a warning that a person could die in bed any night. FitzGerald’s “no such aureate Earth are turn’d” is so Latin that it is now probably difficult for most people to understand. He is saying that the earth in question, a cemetery for the farmers, does not have gold nuggets in it in the form of their corpses. The poet is warning that there is no resurrection, whatever the scriptures might say.

I translated it as free verse poetry in my Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám: a New Translation from the Persian, no. 67.

The poem warns that before fate can ambush you one night, you should order up a glass of rose-red wine. I translated the last two lines this way:

- “For you’re not gold, you old fool — that they’ll bury you

in the ground, then dig you up again.”

This blunt and direct manner of address is faithful to the original, which calls the hearer ghāfel-e nādān “O heedless ignorant one.”

Transliteration:

z-ān pīsh keh bar sar-at shabīkhūn ārand,

farmāy keh tā bādeh’-e golgūn ārand.

to zar na-ī, ey ghāfel-e nādān, keh torā

dar khāk neḥand o bāz bīrūn ārand.

khāk, the Persian for earth or soil, is the origin of our English khaki as the color of a military uniform, which is tan or earth-colored. The British introduced the khaki uniform in India in the 1840s. Persian was used as the language of government in pre-British India, and many Persian words came into Hindustani (which we now call Hindi-Urdu).

—-

Order Juan Cole’s contemporary poetic translation of the Rubáiyát from

or Barnes and Noble.

or for $16 at Amazon Kindle

——

Resurrection and the afterlife are doctrines both of Christianity and Islam, and were adopted in rabbinical Judaism, as well. Mainstream Muslim theologians insisted on them, and denying these tenets was probably dangerous in the medieval period.

The unconventional quatrains collected under the rubric of “Omar Khayyam,” a Seljuk-era astronomer who died around 1131 AD, often deny these doctrines, however. (I don’t think the poetry is actually by Khayyam; it is later and by many poets.) I believe this literature is folk poetry, and represents a stream of Muslim secularism that flourished especially after the Mongol invasions of the 1220s and after. The Mongols were Buddhists and shamanists, and as rulers did not care to enforce Muslim orthodoxy. So for some 80 years, until the Mongol rulers of Iran began embracing Islam, you could get away with saying unorthodox things, and drinking wine. There is a lot of historical evidence for both.

Even once the Mongols became Muslims, they wore their religion lightly, and they were succeeded by Central Asian Turkic rulers, many of them nomads who practiced a folk religion. Some of their rulers were accused, at least, of being atheists, as with the rebel Qara Qoyunlu (Black Sheep) prince, Pir Budak, who took Shiraz briefly in the late 1450s and early 1460s. It was at his court that the calligrapher Mahmud Yerbudaki first assembled a whole book of unconventional quatrains under the title The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, attributing them to the astronomer ex post facto. They had been circulating for some time, listed in manuscripts as anonymous or attributed to other poets. Yerbudaki’s manuscript, which ended up in Oxford University’s Bodleian Library, was one of the two on which FitzGerald depended.

Philosophers such as Avicenna (Ibn Sina, 980–1037 AD) did not accept orthodox theological doctrines about the resurrection of the physical body, so the theme of this poem may have derived from philosophical circles. On the other hand, its simplicity and frankness make me think that it was the work of a simpler sort of person. I suspect a lot of carpenters, tilers and other craftsmen doubted that people were ever going to get up out of their graves, but went along with the preachers for fear of trouble. When they gathered among themselves away from prying eyes, they might read out poetry like this.

From Gilbert James, Fourteen Drawings Illustrating Edward FitzGerald’s translation of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám (London: Leonard Smithers & Co., 1898). Note the influence of Qajar-era modern Persian art.

The poetry ascribed to Khayyam often points out that no one has ever come back from the supposed other world, implying it is because there is no such thing and the dead have disintegrated in the ground.

Here is an example:

افسوس که سرمایه ز کف بیرون شد

وز دستِ اَجَل بسی جگرها خون شد

کس نآمد از آن جهان که پرسم از وی

کاحوالِ مسافران دنیا چون شد؟

I’d translate it in blank verse this way:

How sad that our cash slipped out of our hands,

and that fate’s grip extracted our hearts’ blood;

None came back from that world whom I could ask

what happened to all this world’s caravans.

“Cash” here is literally “capital,” but you get the point. Our short lives ending in death are being compared to bankruptcy and loss of capital. “Heart” in the original is “liver,” and in Persian poetry the liver often functions as “heart” does in English verse. I’m sure it has to do with medieval ideas about humors and the organs of the body. The last two lines imply that the people of the world are traveling toward certain death and extinction, and that is all there is, otherwise we’d have heard back from them.

It is bleak, but sometimes just stating a bleak reality is itself a form of transcendence.

“In this batter’d Caravanserai:” FitzGerald’s translation of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám 1:16

Quatrain 16 in the first edition of Edward FitzGerald’s translation of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám underlines that life is fleeting for everyone, even the rich and powerful, and even for monarchs. FitzGerald was an “entrepreneurial Radical” in Victorian terms, who disliked the aristocracy and favored the republican form of government for newly established nation-states in Europe such as Italy. Singling out kings as a demonstration case of how time holds still for no one may have been a way of subtly expressing this republicanism.

XVI.

- Think, in this batter’d Caravanserai

Whose Doorways are alternate Night and Day,

How Sultán after Sultán with his Pomp

Abode his Hour or two, and went his way.

The original was identified by A.J. Arberry as no. 98 in the Calcutta manuscript that Edward Cowell sent back to FitzGerald in 1857. It can now be found here.

این کهنه رباط را که عالم نام است

وآرامگه ابلقِ صبح و شام است

بزمیست که واماندۀ صد جمشید است

قصریست که تکیهگاه صد بهرام است

My literal translation in iambic heptameter would go this way:

This ancient caravanserai whose nickname is “the world”

provides a dappled refuge for each morning and each eve.

It is a banquet that left a hundred Jamshids behind.

It is a palace where a hundred Bahrams took their rest.

The word for caravanserai here in the original is ribāṭ, which is discussed by J. Chabbi in The Encyclopedia of Islam. In the early centuries of Islam it referred to a military garrison where troops were stationed. However, because it was secure, trading caravans began stopping off at such places, staying the night on their way to their destination. So the word came to have the connotation of inn or caravanserai. In the 1100s and 1200s some ribāṭs began being used as Sufi centers, which established them as a separate space than the mosque, and under the control of spiritual adepts rather than legalistic clergy. The Turkish word khaneqah was also used for such mystical places of retreat.

Here, FitzGerald made a note that the word means caravanserai, and that is certainly correct. For the poets, a caravan is a symbol of impermanence, since it stays on the move.

The great mystic Jalal al-Din Rumi wrote, as well

بس رباطی که بباید ترک کرد

تا بمسکن دررسد یک روز مرد

Many a caravan you must forsake

until you one day reach the dwelling-place.

For Rumi, a pious Sufi, the dwelling-place or permanent abode is union with the divine, whereas in this world of gross matter we just stop off at temporary inns along the spiritual path.

We find a similar trope in Baba Afzal Kashani,

دنیا چو رباط و ما در او مهمانیم

تا ظن نبری که ما در او میمانیم

در هر دو جهان خدای میماند و بس

باقی همه کل من علیها فانایم

The world’s a caravanserai and we’re

its guests; so don’t imagine we’ll stay long.

In both these worlds it’s only God that stays

The rest are but “All on it are fleeting.”

The last quotation in this quatrain is from the Qur’an, 55:26, meaning “all on the surface of the earth are impermanent. It illustrates that the emphasis on the ephemerality of all things found both in mystical and secular Persian poetry has roots in the Muslim scripture. Scripture and the pious drew a different lesson from it than did the secular-minded, though. For the latter, the lesson was that one may as well enjoy the good things of life, since it won’t last long, and they doubted there is an afterlife.

Baba Afzal Kashani (d. c. 1213 or 1214) was a spiritual philosopher and an acknowledged master of the Persian quatrain.

The great William Chittick writes of him,