In Quatrain no. 23 in the first edition of Edward FitzGerald’s translation of The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, we find an explicit denial of the afterlife. This denial is repeated throughout the poetry, and it surely was one of the more challenging themes in this poetry for Victorian Britain and the United States. Of course, since Muslims firmly believe in the afterlife, like rabbinical Jews and like Christians, the rejection of this doctrine was heretical in Iran and Muslim India, as well. Still, these unconventional quatrains containing this bleak teaching circulated for a millennium, attributed to the astronomer Omar Khayyam as a frame author. Scientists in Muslim societies often had a reputation as free-thinkers, so that is perhaps why Khayyam occurred to the poets as a figure to whom this somewhat dangerous poetry could be ascribed. The grimness of the teaching, that life is short and it is all that people get, is leavened throughout the quatrains by lighthearted advice to enjoy yourself while you can. It is the combination of a disavowal of life after death and permission to have some good times that I think helped account for the popularity of these verses in Iran, India, Central Asia and the Ottoman Empire, and then in Britain and America.

This is FitzGerald’s no. 23 in the first edition:

XXIII.

Ah, make the most of what we yet may spend,

Before we too into the Dust descend;

Dust into Dust, and under Dust, to lie,

Sans Wine, sans Song, sans Singer, and-sans End!

One of the reasons I made a contemporary translation of the Rubáiyát is that some of FitzGerald’s vocabulary from 1859 is now dated. It used to be that most educated people knew some French, but I’m not sure how true that is any longer, and using the French sans to mean “without” might not be meaningful to some readers today.

A. J. Arberry believed that this quatrain was another of FitzGerald’s composites, wherein he took two verses from one quatrain and then two from another.

He thought the first two lines were from no. 76 in the Bodleian manuscript, which is also in the Calcutta MS as no. 177 (which has some minor variants). It is also here.

مگذار که غصّه در کنارت گیرد

و اندوه محال روزگارت گیرد

مگذارکتاب او لب یار و لب کشت

زان پیش که خاک در کنارت گیرد

I translated the first two lines this way (no. 75) in my modern edition of the Rubáiyát:

- Don’t let sadness dig its hooks in you;

don’t let misery eat up your days

The last two lines come from the first two in no. 35 in the Bodleian manuscript, no. 83 of the Calcutta. It is also here.

می خور که به زیرِ گِل بسی خواهی خفت

بی مونس و بی رفیق و بی همدم و جفت؛

زنهار به کس مگو تو این رازِ نهفت

هر لاله که پَژْمُرد، نخواهد بِشْکفت

I translated the first two lines here (no. 34) in free verse this way:

- Here, have a drink, since you’ll be sleeping for a long time underground,

without a best friend, or soul mate or lover.

—-

Order Juan Cole’s contemporary poetic translation of the Rubáiyát from

or Barnes and Noble.

or for $16 at Amazon Kindle

——-

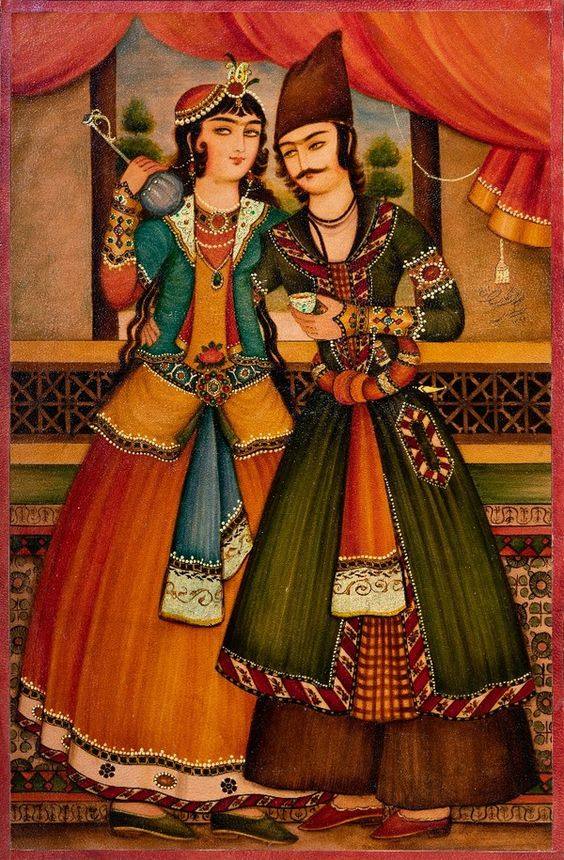

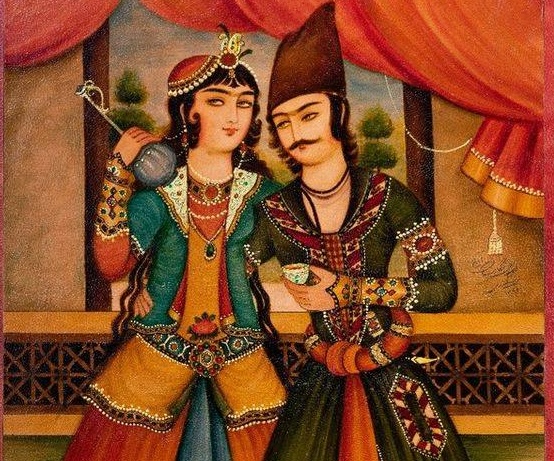

Couple drinking Shirazi wine. Oil on Canvas, 19th century Qajar Dynasty, Reza Abbasi Museum, Tehran Iran. Public Domain. H/t Persian Version

The sentiments in the poems attributed to Khayyam were hardly limited to this corpus. They are also met with in Hafez of Shiraz (d. 1390), though he does not make explicit the lack of an afterlife, only speaking of how we’re doomed to become dust. Take for instance the beginning of this ghazal (a sort of Persian sonnet):

خیز و در کاسهٔ زر آبِ طَرَبناک انداز

پیشتر زان که شَوَد کاسهٔ سَر خاک انداز

عاقبت منزلِ ما وادیِ خاموشان است

حالیا غُلغُله در گنبدِ افلاک انداز

I would render this one in iambic hexameter:

Get up, pour liquid joy into a golden bowl,

Before that handsome skull of yours is filled with dust.

For in the end, our home’s the valley of silence.

For now, make a great din beneath the heaven’s dome.

The first four lines of this ghazal of Hafez could easily be a quatrain in the Omarian corpus. The difference is that Hafez did not explicitly come out and say there would be no resurrection from the dead, whereas the Omarian poems do.

—-

For more commentaries on FitzGerald’s translations of the Rubáiyát, see

FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám: Commentary by Juan Cole with Original Persian

© 2026 All Rights Reserved

© 2026 All Rights Reserved