Massoud Hayoun, ‘Sick of foul, I’ll take the goat,’ 2024. Acrylic on canvas, [91.4 x 121.9 cm (36 x 48 in). Photo courtesy of the Larkin Durey gallery, London.

( Globalvoices.org ) – In his new series “Stateless,” presented this summer at Larkin Durey in London, Massoud Hayoun turns painting into a vivid negotiation between memory, exile, and political resistance. The eight works, rendered in spectral shades of blue, channel his family’s history — Tunisian, Moroccan, Egyptian, and Jewish — while confronting the broader architectures of displacement and power.

Critics praised the exhibition’s emotional coherence and bold humor, framing it as a declaration of belonging and a refusal to let systems of erasure define Arab identity. Hayoun’s canvases unfold like cinematic tableaus: the living and the dead, icons of Arab cinema, and imagined ancestors, all inhabiting a color palette that makes ghosts visible.

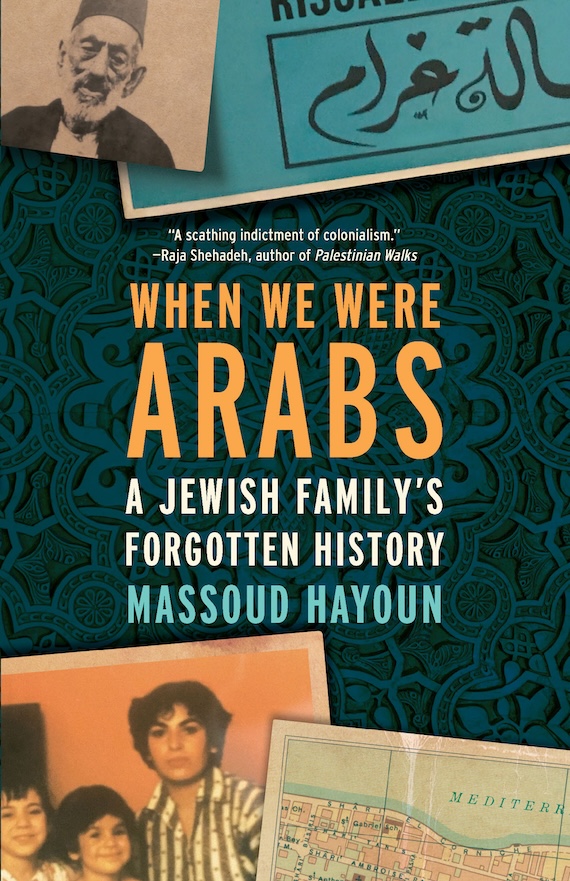

Raised in Los Angeles by his grandparents, Hayoun inherited their stories of a “Zaman al-gameel,” the golden age of Arab cinema, alongside the lived weight of colonial hierarchies. His grandmother, who began drawing fantastical creatures at the end of her life, left him with the sense that reinvention is always possible. Mourning her loss and navigating the solitude of the pandemic, Hayoun shifted from a career in journalism and authorship, including his acclaimed book “When We Were Arabs,” to painting as his central artistic language.

![Massoud Hayoun, Life's Nectar, 2024, recto, Acrylic on canvas, 30 x 40 in [76.2 x 101.6 cm]. Photo: courtesy of the Larkin Durey gallery, London.](https://globalvoices.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Massoud-Hayoun-Lifes-Nectar-2024-recto-Acrylic-on-canvas-30-x-40-in-76.2-x-101.6-cm.jpeg)

Massoud Hayoun, ‘Life’s Nectar,’ 2024. Acrylic on canvas, 76.2 x 101.6 cm (30 x 40 in). Photo courtesy of the Larkin Durey gallery, London.

In an interview with Global Voices, Hayoun spoke about the relationship between writing and painting in exploring heritage, the symbolism of his recurring blue palette, the influence of his grandparents on his aesthetic sensibility, and how he envisions his art as a human conversation about identity, power, and resistance.

Excerpts from the interview follow.

Massoud Hayoun, ‘Anatomy of a Raid,’ 2025. Acrylic on canvas, 101.6 x 76.2 cm (40 x 30 in). Photo courtesy of the Larkin Durey gallery, London.

Omid Memarian (OM): In your experience, how do writing and painting differ in facilitating a connection with your identity and heritage?

Massoud Hayoun (MH): I wrote a book exploring Arabness through recent history, current events, and the lives of my grandparents. It focused on Arabs of Jewish faith, because while there were books about Jews from Arab countries, none addressed the intersection of these identities or the policies designed to alienate people from their homelands. I used policy documents, letters, and curricula to make an argument that challenged popular Western understandings of Arabness.

Many will still see my Arabness and Judaism as mutually exclusive, because their views are so ingrained. I can spend my life making those arguments, or move on as an Arab American of Jewish faith who makes art for Arab and human liberation.

My painting isn’t religious, as I oppose institutional spirituality, what Diego Rivera called mass-psychosis. My paintings are for the diverse Arab peoples — not specifically Jewish, Tunisian, Egyptian, or Moroccan — but for all who identify as Arab. More broadly, they are for humans who no longer believe in systems of control and the murderous bigotry guiding power today.

Massoud Hayoun, ‘Don’t trifle with the cat women of Alexandria in the summertime • Feu follet,’ 2024. Acrylic on canvas, 121.9 x 91.4 cm (48 x 36 in). Photo courtesy of the Larkin Durey gallery, London.

OM: A conversation with Ai Weiwei, who praised your debut novel as “exquisite,” inspired you to delve deeper into painting. How has this interaction influenced your artistic direction and the themes you explore in your visual work?

MH: I was working a part-time job billing medical insurance in the later part of the pandemic, hating every day. I sent the manuscript to Ai Weiwei, expecting him to ignore it. Suddenly, I got an email saying he wanted to FaceTime. I called him from the lunch space. I lived in China for some years, so speaking my rusty Chinese added to the hallucinatory vibe. We talked about China, art, and life. He was eating a peanut butter sandwich and talking to me about exile. The power of that moment and the spiritual generosity made me start thinking about art as a human endeavor.

I started making appointments with gallerists in LA, not to show my work, but to ask if people could show professionally after pursuing other careers. At times, I felt disheartened. I don’t know how to drive, and gallerists in LA are in far-flung neighborhoods. I was walking for miles, overthinking, and feeling, on occasion, like an idiot for trying.

I still feel that way, sometimes. Ai Weiwei is a touchstone in those moments. I’ll keep going.

Massoud Hayoun, ‘Uncynical Tunisian love painting,’ 2024. Acrylic on canvas, 101.6 x 76.2 cm (40 x 30 in). Photo courtesy of the Larkin Durey gallery, London.

OM: Raised in Los Angeles by your Tunisian and Moroccan-Egyptian grandparents, how did your upbringing shape your artistic sensibilities? Additionally, how has your life evolved since embracing the role of a visual artist?

The Arabness and Tunisian, Moroccan, Egyptian-ness of the paintings comes from my grandparents’ generation: the nearly forgotten Zaman al-gameel, the golden age of Egyptian cinema, the Nahda period, and the strange space they occupied in the colonial hierarchies of their homelands. What is more modern comes from my travel back to our countries and relationships with Arab Americans.

The art allows me to spend time with my grandparents and others from the past. It is fulfilling but also emotionally depleting. It is daunting and electrifying, causing great suffering, yet it is the only thing that alleviates it. It is lonely, but it also cures my loneliness. I wouldn’t paint if I were especially strong or happy. The anxieties of deadlines, pushing past limits, and navigating others’ needs are the same as in journalism or book writing.

Massoud Hayoun, ‘Alexandria, Momentarily,’ 2024. Acrylic on canvas, 121.9 x 91.4 cm (48 x 36 in). Photo courtesy of the Larkin Durey gallery, London.

OM: Your book “When We Were Arabs” intertwines personal memoir with broader political narratives. What core message did you aim to convey through this work, and how does it reflect your views on Arab-Jewish identity?

MH: It is intended as a political theory of Arabness and belonging as related to and illustrated by current events and the lives of my grandparents, who raised me. I wanted a work like this to exist as a touchstone for myself and for other people of Arab origin, as well as those interested in understanding our region. I’m thankful for the attention it received. On occasion, I receive requests to speak about it at a university. With little exception for those who demonstrate how it will contribute to important conversations on human rights, I decline. Not to be a jerk, but because I said what needed to be said. I gave the evidence for it. I wrote it while in mourning for my grandmother, and my mind worked in such a way that it scabbed over that writing experience. It’s time for me to move forward, underpinned by the understandings in the book, and to devote my intellectual labor through these paintings to the ideals I discussed in words in the book.

Massoud Hayoun, ‘Portrait of the inverse of a woman,’ 2024. Acrylic on canvas, 121.9 x 91.4 cm (48 x 36 in). Photo courtesy of the Larkin Durey gallery, London.

OM: Critics have highlighted the symbolic depth in your paintings, often rendered in shades of blue. Could you discuss your visual process and the significance of this color palette in conveying themes of exile, love, and resistance?

MH: Symbolism is how I was raised. My grandparents, mostly practical and socialist, were North African and on occasion espoused superstitions, tying significances to objects. I was raised to think that way, and it informs the symbols in my work.

Cinema also informs my work. My grandfather was born in Egypt when it was making some of the best films. I was born in Los Angeles, the capital of both pornographic and mainstream film. I moved to Hong Kong and China because I loved the films of Wong Kar-wai. Once, in a film my family bought me on VHS — I saw a ghost. Electric blue. To me, that blue with glowing highlights and shadows is ghostly.

At first, just my grandparents and the dead were blue. Then everyone I described in the past tense became blue. In self-portraits, the me I describe is no longer the me who looks back later. That is life — this precious, miraculous, wondrous, continual kick in the teeth that is life.

Massoud Hayoun, ‘Stateless • Por no llevar papel,’ 2024. Acrylic on canvas, 121.9 x 91.4 cm (48 x 36 in). Photo courtesy of the Larkin Durey gallery, London.

OM: Your work frequently addresses themes of belonging and the intricate webs of power. How do you navigate these complex topics in your art?

MH: With every piece, there is an immediate idea — something in the news or a recollection — and a grander idea, political, philosophical, or psychological.

The hope is that people spend enough time to see more than the immediate. However, as a journalist, I know that time is earned. At least they might appreciate the weirdness, the sense of humor, or other particularities of what each work is trying to achieve.

The work is Arab, by and for the diverse Arab peoples. But it is beyond that, thoroughly human. I envision the audience as humans of all backgrounds, interested in the human condition, yearning for better times, and struggling, as I do, to imagine those futures. The hope is they see these as human works, conversations with humans thirsting for life about where we are and what comes next.

© 2026 All Rights Reserved

© 2026 All Rights Reserved