Lincoln, NE (Special to Informed Comment; Feature) – Long before Israeli leaders invoked biblical rhetoric to justify the “erasure” of a Palestinian homeland, another colonizing people sought to remake a land in the image of their God. In July 1847, Brigham Young declared the American Great Basin “the place” God had set apart to “make” Mormons. And yet as Young—the president and prophet of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints—mapped out in his mind’s eye a Mormon Zion across the Wasatch Front, that land was already home to a powerful Indigenous nation, the Utes. Their most formidable leader was Wakara (1815–1855), a brilliant and ambitious figure whose life I chronicle in Wakara’s America: The Life and Legacy of a Native Founder of the American West.

Like Palestinians, Wakara’s Utes lived in close relation to their land and water, managing them with care and reverence. Like Gazans, they faced a flood of settlers, many of whom saw their very existence as an obstacle to the fulfillment of divine commandment. And like so many colonized people, their demands for sovereignty and dignity were met with war. The “peace” that followed led to attempts at cultural and physical erasure.

For more than five centuries before the settlers’ arrival, Wakara’s Timpanogos band stewarded interconnected ecosystems they called “earths.” “Lower earth” centered on Timpanogos Lake (Utah Lake), whose abundant fisheries Wakara’s peopled managed through traditional ecological knowledge. In “middle earth,” rich grassy plains and foothills, they gathered fruits and roots. In the high mountains of “upper earth,” they hunted game. After adopting the horse—among the first Native nations to do so—Wakara’s Utes traveled beyond these earths to hunt bison and trade.

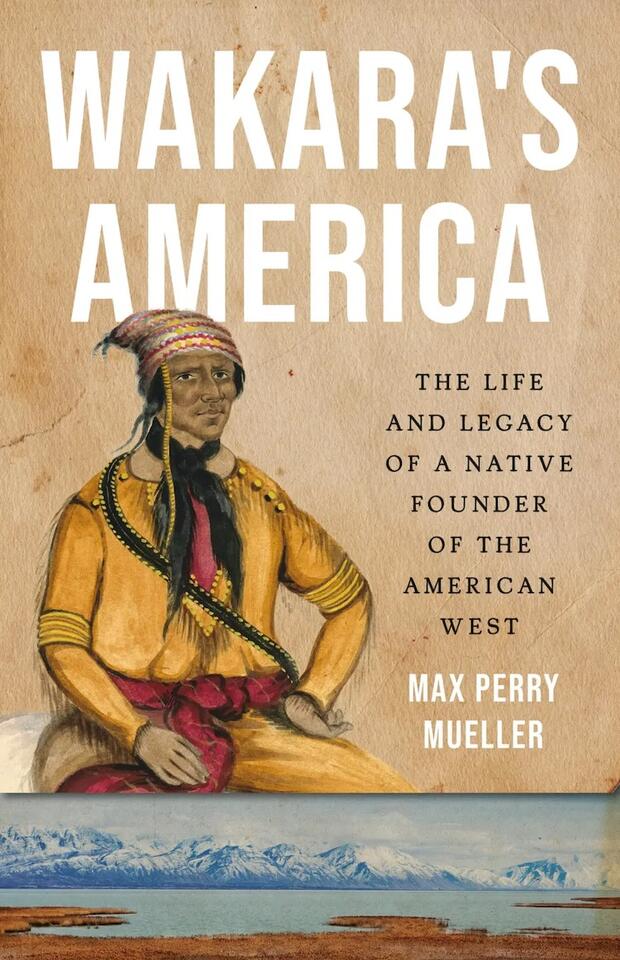

Out of these “fish eaters” who became a horse nation rose Wakara. From 1840 onward, Wakara and his cavalry dominated broad stretches of the Southwest, from Santa Fé to Southern California. Wakara was a trader, diplomat, and strategist, able to negotiate with Mexicans, Americans, and Indigenous nations. He also engaged in violent commerce, raiding horses by the thousands in California and enslaving pedestrian Paiutes, selling both horses and people in New Mexican and Californian markets.

When Young and his fellow settlers arrived in Utah in 1847, Wakara welcomed them. For a time, Young and Wakara—the two most powerful men in the American Southwest—used each other to expand their empires. For Wakara, the Mormons became markets for trade in horse and human flesh. For Young, Wakara became a supplier of horses and Indian slaves, as well as a guide through unfamiliar territory, which facilitated the expansion of the Mormons’ so-called Zion in the Mountain West.

Partnership gave way to occupation. To irrigate their crops, the swelling number of Mormon settlers diverted rivers and dammed creeks, destroying grasslands. When crops failed, Mormons overfished the fisheries that Wakara’s Utes had carefully managed for generations. The Mormons also cut off trade routes and treated seasonal Ute migrations as trespass. Hungry Utes killed Mormon cattle and took grain. Declaring these acts “depredations,” Young sanctioned what settlers called “extermination” campaigns. The conflict that erupted in 1853—remembered as the “Walker War”—was, as I argue in Wakara’s America, initiated and executed by Young. His militias massacred unarmed Native people seeking food and shelter and poisoned land and water through a tactic they called “seasoning.” This was no misunderstanding; it was a deliberate campaign to break Ute land claims under the banner of settler security. Thus, it’s more accurate to call it “Brigham’s War.”

In May 1854, after a year of bloodshed and hunger, Wakara and Young met and agreed to peace. In exchange for the use of Ute lands, Young agreed to supply Wakara’s Utes with beef and grain upon which they relied due to the destruction of their hunting and fishing grounds. In January 1855, Wakara died suddenly—perhaps from disease, perhaps from poison. Over the next decade, thousands more Utes died from sickness, starvation, and warfare. Survivors were driven onto reservations where they were corralled, surveilled, and starved.

A similar story has unfolded in Gaza. For decades, Gazans have had their mobility restricted, their economies strangled, their waters and lands poisoned. In response, when some Gazans carried out acts of violence—evil as those acts were—they were invoked to justify collective punishment and extermination.

And yet in the face of total war—and the so-called peace that followed, Gazans, like Wakara’s Utes before them, have proven steadfast (sumud), nonviolently resisting and enduring their erasure. They rebuild destroyed homes using salvaged materials. They dig temporary wells. They replant olive trees. They make art.

If a just peace is to follow this war against Gazans, which guarantees security and sovereignty for both Palestinians and Israelis, the global community must refuse the erasure that followed Brigham’s War against Wakara’s Utes, and so many like it. Such a peace requires a full accounting of what happened, accountability for those who carried out genocidal acts, and sustained support for displaced people to return and rebuild their homelands. Only through truth, accountability, and restoration can peace lay the foundation for a shared and livable future.

© 2026 All Rights Reserved

© 2026 All Rights Reserved