With no. 19 in in the first edition of Edward FitzGerald’s The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, the theme turns away from the glory of kings as a flash-in-the-pan to the impermanence of life for everyone. One of the tropes common in the subsequent poems, already used in no. 18, is that we are clay and go back to clay when we die, so that the grass grows from the dead of previous generations. Thus, enjoying sitting in a meadow with its greenery should remind us that beneath the herbage are legions of corpses now returned to dust.

ΧΙΧ.

And this delightful Herb whose tender Green

Fledges the River’s Lip on which we lean —

Ah, lean upon it lightly! for who knows

From what once lovely Lip it springs unseen!

The source is no.. 46 of the Calcutta manuscript, also found here:

هر سبزه که بر کنار جویی رسته ست

گویی ز لب فرشتهخویی رسته ست

پا بر سر سبزه تا به خواری ننهی

کآن سبزه ز خاک لالهرویی رسته ست

My blank verse version isn’t strictly literal but may give something of the flavor of the original:

The grass that decorates the river bank

has sprung from a sweet belle with angel lips.

Don’t trample on the lawn disdainfully:

The dust of a seductress gives it life.

This stanza uses the language of love poetry ironically, speaking of how precious the lips of a stunner with an angelic face are, and how attractive a young woman with rouged cheeks is (cheeks like a red tulip). But then, like a horror writer, it reminds us that past such gorgeous beloveds were doomed to push up daisies. At least, the poetry says, we should be nice to the daisies, considering who pushed them up. It reminds us that the objects of our most powerful romantic passions are doomed to become compost for the greenery above the tombs.

—-

Order Juan Cole’s contemporary poetic translation of the Rubáiyát from

or Barnes and Noble.

or for $16 at Amazon Kindle

——-

The mystic Jalal al-Din Rumi, who unlike the atheistic Khayyami poetry celebrated the quest of the human soul to be united with the divine beloved, used these symbols very differently. In his lyrical poetry for his dear friend Shams of Tabriz, Rumi wrote of the possibility of spiritual transformation referring to grass and graves

تا سبزه گردد شورهها تا روضه گردد گورها

انگور گردد غورهها تا پخته گردد نان ما

So that our salt flats may become greenery

and our graves be turned into a garden;

So that green grapes may become purple-sweet

and our dough become cooked bread…

We can see here hope for the fulfillment of the soul through its approach to God, and the symbols for its maturing. Rumi also spoke of grass or greenery and graves, but he uses these terms in a hopeful way, the opposite of the Khayyami cynicism.

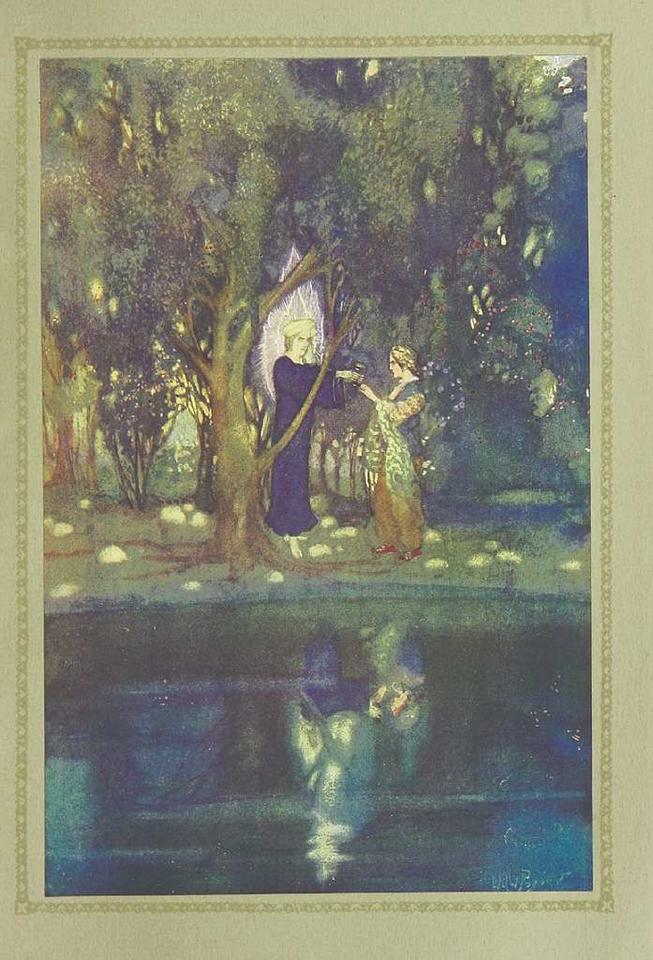

Illustration from The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám by Willy Pogany. Lithograph-printed by McLagan & Cumming of Edinburgh. London: George G. Harrap & Co., 1909. Public Domain.

Hafez of Shiraz has a passage that is closer to this quatrain attributed to Khayyam, in its nostalgia for a past that cannot be recovered:

اوقاتِ خوش آن بود که با دوست به سر رفت

باقی همه بیحاصلی و بیخبری بود

خوش بود لبِ آب و گل و سبزه و نسرین

افسوس که آن گنجِ روان رهگذری بود

The good times were those spent with a friend

The rest was fruitless oblivion.

Happiness was the banks of the stream, flowers, greenery and wild roses

Too bad that this flowing treasure was just passing by.

Life hurries by, and when we look back, the time we spent with a dear friend or beloved surrounded by the beauties of nature are all that will still be meaningful to us.

Despite its cynicism, I think there is in the Khayyami poetry some of this sort of downplaying of materialism and ambition as the sources of meaning in life, and an attempt to draw our attention to how important it is to stop and smell the roses, before we become their food.

—-

For more commentaries on FitzGerald’s translations of the Rubáiyát, see

FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám: Commentary by Juan Cole with Original Persian

© 2026 All Rights Reserved

© 2026 All Rights Reserved