Stanza no. 24 in the first edition of Edward FitzGerald’s translation of The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám makes fun, as A. J. Arberry pointed out, of theologians and philosophers who spoke of metaphysical certainties. Personally, I think there is something almost Buddhist about it (see below).

XXIV.

Alike for those who for to-day prepare,

And those that after a To-morrow stare,

A Muezzín from the Tower of Darkness cries

“Fools! your Reward is neither Here nor There!”

A. J. Arberry identified the original here as no. 411 in the Calcutta MS:

قومی متفکّرند در مذهب و ز ین

جمعی متحّیرند در شکّ و یقین

ناگاه منادئی برآید ز کمین

کای بیخبران راه نه آنست و نه این

It is replicated almost identically on the web here.. A slightly different version also exists.

In the Calcutta MS., “o z īn” or “wazīn” is almost certainly a mistake for “dīn” or religion.

Here is my attempt at a relatively faithful rendering of the original, in iambic pentameter but with an abba rhyme scheme rather than FitzGerald’s aaba. I find it almost impossible to achieve the latter while keeping the strict sense of the Persian, which is why my own translation of The Rubáiyát is in blank or free verse.

Some meditate on faith, amazed thereat;

one group is lost in certainty and doubt.

A crier then cried out from a redoubt:

“You fools, the path is neither this nor that!”

—-

Order Juan Cole’s contemporary poetic translation of the Rubáiyát from

or Barnes and Noble.

or for $16 at Amazon Kindle

——-

FitzGerald made the “crier” as in “town crier,” into a Muslim caller to prayer or muezzin. In keeping with the spirit of the original, he depicted the minaret as a “Tower of Darkness,” suggesting that a conventional, fundamentalist faith is benighted, and it is necessary to transcend the superficial binary of doubt and certainty, unbelief and faith.

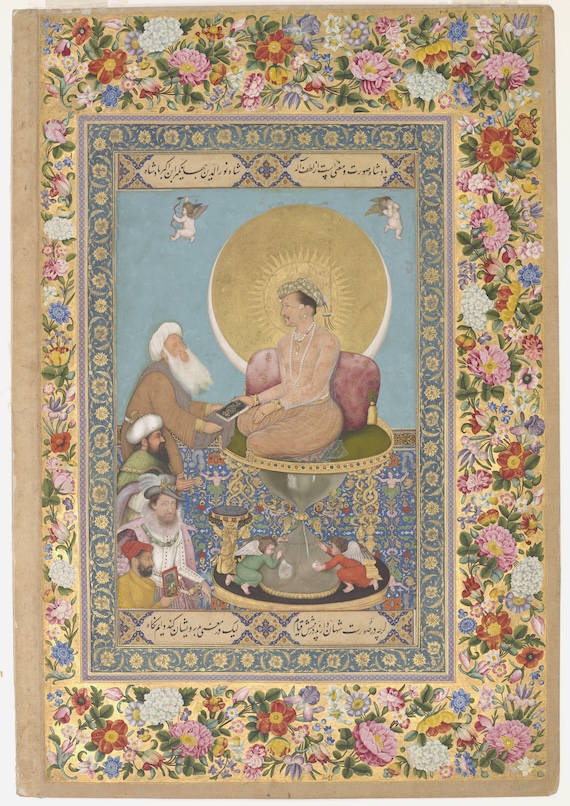

(Artist) Bichitr. Mughal Emperor Jahangir Preferring a Sufi Shaikh to Kings, ca. 1615-1618. From the St. Petersburg Album. Freer Gallery. Smithsonian Institution.

The assertion that the path is “neither this nor that” recalls the notion in the Upanishads of “neti, neti” — that language is inadequate to understanding the divine or the human self, and so whatever attributes are proposed of either should be seen as constructs rather than reality.

Swaran P. Singh writes in an article on mindfulness :

- “A particular form of negation, neti neti, is salient in all main Indian traditions. Neti neti (not this, not this) is a method of inquiry to find out what you are not: I am not this body, I am not these emotions, I am not this thought or experience, etc. By negating everything that is ‘not-self’, one is left with only the self.”

This principle of “not this, not that” also resembles Zen Buddhist ways of thought.

I argued in my book about the The Rubáiyát that much of the poetry was composed in Mongol or post-Mongol times when Buddhism had an influence on Iran and Central Asia.

It is also possible that many of the quatrains in the Calcutta manuscript that E. B. Cowell found in the Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal collection were written in India by Indians. Many people contributed to this genre of poetry and attributed the poems to Khayyam as a frame author, just as the 1001 Nights tales were composed in Cairo, Baghdad, Aleppo and elsewhere and attributed to Scheherazade. If the poem is Indian, it could by by a Hindu who knew the “Neti, Neti” of the Upanishads, or by a Muslim who did. Medieval Indian Persian culture was cosmopolitan and the Upanishads were translated into Persian by the Mughal Prince Dara Shikoh.

Of course, sophisticated Sufi or mystical Islamic thought is full of such spiritual concepts in its own right.

While much of the Khayyami corpus adopts a sneering tone toward conventional religion, in some instances it suggests that the search for transcendence can be rewarding if only it is approached with wisdom and while avoiding simplistic piety.

—-

For more commentaries on FitzGerald’s translations of the Rubáiyát, see

FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám: Commentary by Juan Cole with Original Persian

© 2026 All Rights Reserved

© 2026 All Rights Reserved