Quatrain 17 of the first edition of Edward FitzGerald’s the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám continues the theme that kingly glory quickly fades.

XVII.

They say the Lion and the Lizard keep

The Courts where Jamshyd gloried and drank deep:

And Bahrám, that great Hunter — the Wild Ass

Stamps o’er his Head, and he lies fast asleep.

A. J. Arberry, Romance of the Rubaiyat, p. 203, says it is based on no. 102 in the Calcutta manuscript:

آن قصر که بهرام در او جام گرفت

روبه بچه کرد و شیر آرام گرفت

بهرام که گور میگرفتی دایم

امروز نگر که گور بهرام گرفت

He translates it:

That palace in which Bahram took the cup,

(there) the fox has whelped, and the lion taken its rest;

Bahram who used always to take the wild ass (gur)–

today see how the grave (gur) has taken Bahram.

He thinks FitzGerald took the reference to Jamshid from another quatrain in that manuscript.

The quatrains in this series strike me as similar in theme and purpose to the poem “Ozymandias,” by Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792 – 1822), published in 1818:

- “I met a traveller from an antique land

Who said: ‘Two vast and trunkless legs of stone

Stand in the desert . . . Near them, on the sand,

Half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown,

And wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command,

Tell that its sculptor well those passions read

Which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things,

The hand that mocked them, and the heart that fed:

And on the pedestal these words appear:

‘My name is Ozymandias, king of kings:

Look on my works, ye Mighty, and despair!’

Nothing beside remains. Round the decay

Of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare

The lone and level sands stretch far away.'”

The poem referred to the Egyptian Pharaoh Ramses II. Shelley was a fierce republican who hated kings, and no doubt enjoyed pointing to the fleeting character of their glory, and here he parodies their hubris. FitzGerald was not as openly political as Shelley, whose works he loved, but he did at one point express a hope that Italy would emerge as a republic and that its people would gain their freedom.

I had placed the below discussion of Bahram in the commentary on 1:16 but I think it belongs better here. I expanded instead for 1:16 on the meaning of the “caravanserai” in Persian poetry.

—-

Order Juan Cole’s contemporary poetic translation of the Rubáiyát from

or Barnes and Noble.

or for $16 at Amazon Kindle

——-

I talked about the ancient mythical king of Iran, Jamshid, in an earlier commentary.

Bahram V or Bahram Gor was a king of the Sasanian dynasty who ruled 420-438 CE. He was a contemporary of the Eastern Roman Emperor Theodosios II. While he was a historical figure, he entered the epics and romances of later poets such as Ferdowsi and Nezami.

His historical adventures were amazing enough. He had been exiled to the vassal Arab court at Hira, and when his father Yazdegerd was killed by increasingly powerful Zoroastrian priests, they initially tried to put Khosrow on the throne. Bahram got Arab help to go to the capital and make a bid for the succession himself. He argued that the crown should be placed in an arena between two wild lions, and whoever could retrieve it by killing the lions would be king. It was agreed, and he dispatched the beasts and won the crown. He pushed back against priestly power. Otakar Klima wrote,

- “He also remitted taxes and public debts at festive occasions, promoted musicians to higher rank and brought thousands of Indian minstrels (lūrīs) into Iran to amuse his subjects, and he himself indulged in pleasure-loving activities, particularly hunting (his memorable shooting of a wonderful onager, gōr, is said to have given origin to his nickname Gōr “Onager [hunter]”). These measures made Bahrām one of the most popular kings in Iranian history. Right after his accession, he proved himself in battle against the White Huns (the Hephthalites) who had invaded eastern Iran. Leaving his brother Narseh as regent, Bahrām took the road from Nisa via Marv to Kušmēhan, where he fell upon the enemy, won a resounding victory, and obtained precious booty from which he made rich offerings to the fire temple of Ādur Gushnasp.”

O. Klíma, “Bahrām V,” Encyclopaedia Iranica, III/5, pp. 514-522, available online at http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/bahram-05 (accessed on 30 December 2012).

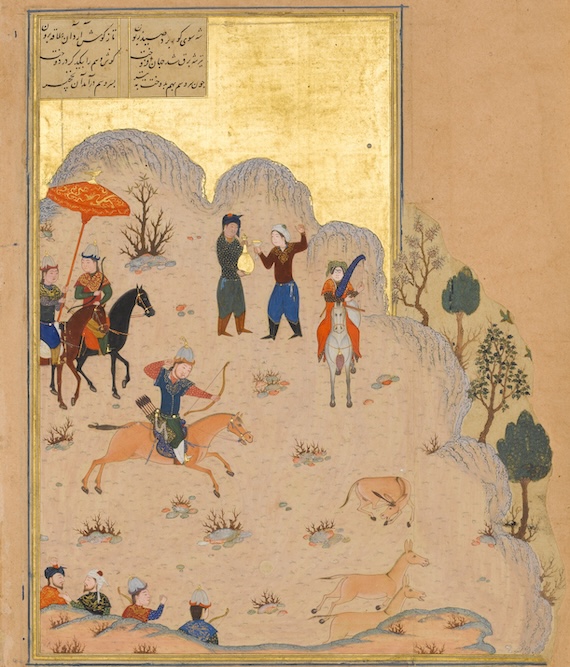

Scenes of Bahram V hunting were a favorite with painters of Persian miniatures, as below:

“Bahram Gur’s Skill with the Bow”, Folio 17v from a Haft Paikar (Seven Portraits) of the Khamsa (Quintet) of Nizami of Ganja. Author: Nizami (present-day Azerbaijan, Ganja 1141–1209 Ganja). Calligrapher: Maulana Azhar (died 1475/76). Date: ca. 1430. Herat, present-day Afghanistan. Medium: Ink, opaque watercolor, and gold on paper. Public Domain. Metropolitan Museum.

The Met explains: “Depicting the Persian hero Bahram Gur hunting with his harp‑playing companion Azada, this painting is one of five illustrations created for a fifteenth-century manuscript of Nizami’s Haft Paikar (Seven Portraits). The manuscript was produced in the celebrated kitabkhana (workshop) established by the Timurid prince Baisunghur (r. ca. 1420–33) during his governorship at Herat. This important workshop created some of the canonical illustrations to Nizami’s text—immediately recognizable, repeated, and emulated over the subsequent centuries.”

—-

For more commentaries on FitzGerald’s translations of the Rubáiyát, see

FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám: Commentary by Juan Cole with Original Persian

© 2026 All Rights Reserved

© 2026 All Rights Reserved