Stanza 32 of the first edition of Edward FitzGerald’s The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám stands as another in a series of existentialist quatrains that stress the inscrutability of death. That is, the poetry questions the meaning of death as a way of questioning the meaning of life.

ΧΧΧΙΙ.

There was a Door to which I found no Key:

There was a Veil past which I could not see:

Some little Talk awhile of Me and Thee

There seemed and then no more of Thee and me.

A. J. Arberry identified the source as no. 403 of the Calcutta manuscript. It is now on the web here.

اسرار اَزَل را نه تو دانی و نه من

وین حرفِ معمّا، نه تو خوانی و نه من

هست از پس پرده گفتوگوی من و تو

چون پرده برافتد، نه تو مانی و نه من

This is my rendering of it as a Fourteener or iambic heptameter:

Not you nor I have known the secrets of eternity.

Not you nor I have solved the riddle that the letter hides.

For there behind the curtain there is talk of you and me,

but when at length the curtain’s drawn, not you remain nor I.

—-

Order Juan Cole’s contemporary poetic translation of the Rubáiyát from

or Barnes and Noble.

or for $16 at Amazon Kindle

——-

The reference in the second line to the “letter of the riddle” probably concerns the Sufi “science of letters” (`ilm al-huruf), which Gerhard Böwering explained. In part, it sees the Arabic letters as creative and powerful in their own right. Thus the Arabic equivalents of ‘k’ ‘w’ and ‘n’ make up kawn or being. The Qur’an speaks of God creating things out of nothing. He says “Be!” (kun!) and it is. So ‘k’ and ‘n’ are the building blocks of the universe.

As in Hebrew, each Arabic letter has a number equivalent, so one word or phrase can be read as equivalent to another that adds up to the same sum — the science that in Kabbala is called gematria.

Line two of the poem, however, concludes sadly that the unidentified letter in question is a riddle that cannot be solved or “read.”

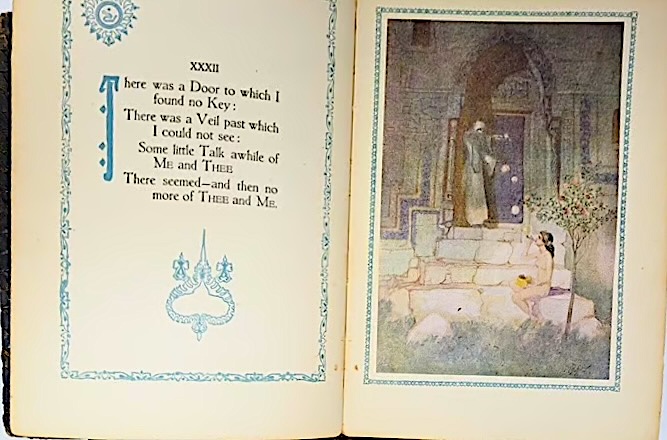

Illustration by Willy Pogany for a 1909 edition of the Rubáiyát. Public Domain.

Vinnie-Marie D’Ambrosio (Eliot Possessed, New York University Press, 1989, p. 188) saw an echo of this quatrain at the end of modernist poet T. S. Eliot’s 1922 “The Waste Land,” a despairing postmortem on the Lost Generation of WW I and after, referring to FitzGerald’s lines, “There was a Door to which I found no Key:/ There was a Veil past which I could not see.”

Eliot wrote toward the end of The Waste Land :

- Dayadhvam [“Compassion”]: I have heard the key

Turn in the door once and turn once only

We think of the key, each in his prison

Thinking of the key, each confirms a prison

Only at nightfall, aethereal rumours

Revive for a moment a broken Coriolanus.

As in the Rubáiyát, the door does not really have a key, since it is implied that it was locked but could not be reopened, and behind it each person is imprisoned. That key-less door behind which we subsist summed up for Eliot, as it had for FitzGerald, the modern condition of alienation. Yet FitzGerald’s original metaphor simply conveyed the skepticism of the Persian original, the author of which could see no way forward to solving the puzzle of existence and death.

That Eliot had originally wanted to end the poem by quoting the ending of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, where Kurtz says, “The horror, the horror,” suggests that he saw WW I as of a piece with the brutalities of European colonialism (the Belgian Congo was the greatest genocide proportionally of any colonial venture, since it seems to have polished off half the 16 million Congolese). These atrocities at the time marked for him the human condition, or at least signaled the decadence of European civilization. He was at that time deeply depressed and suffering from some sort of recurring neurosis, and was anxious about his mentally fragile wife’s health.

This despair is embedded in a long ending passage drawn from the Hindu work, the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, Book Five, V.ii. This section is summarized clearly here.

In it, Brahma or Prajapati addresses three orders of beings, the gods, humans and demons. He instructs them to their better natures with the single syllable, “Da!” and they finish his thought. The gods discerned him to mean “damayat” — control or self-discipline. Humans heard “Da!” to imply datta — to be giving and generous. The demons (in Hinduism not necessarily evil but who flirted with the dark side and could give themselves over to greed, lust and other sins) heard “Da!” as a command to engage in compassion or Dayad-hyam.

Eliot prefaced this section of “The Waste Land” with this instruction of “Be Compassionate” in Sanskrit, suggesting that he thought the people of the post-War period were akin to the Hindu demons or asuras — beset by immoderate passions. Certainly, they had polished off some 11 million people with war lust. Likewise, he references Shakespeare’s tragedy about the Roman General Coriolanus, who is exiled, allies with enemies of Rome against his own city, and then is betrayed and killed by his new supposed allies. Coriolanus was in a prison of his own making, of multiple betrayals — just as were the world’s nations after the revelation that there could be a murderous, fruitless World War.

While the Upanishads offered people a way out of their unfortunate condition, Eliot seems not to think that the asuras of 1922 would take the advice to be compassionate but would instead remain locked up behind a door with no key (or with a key that only worked once, to imprison these demons in their passions).

If D’Ambrosio is correct about the reference to the Rubáiyát 1:32 in this passage of “The Wasteland,” it shows the way that Eliot tempered the optimism of the Upanishads with medieval Iranian and Victorian modernist pessimism about the human condition.

—-

For the previous quatrain, see “Through the Seventh Gate:” FitzGerald’s The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám 1:31.

For more commentaries on FitzGerald’s translations of the Rubáiyát, see

FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám: Commentary by Juan Cole with Original Persian

© 2026 All Rights Reserved

© 2026 All Rights Reserved