By Gary W. Yohe, Wesleyan University

(The Conversation) – In 2009 the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency formally declared that greenhouse gas emissions, including from vehicles and industry, endanger public health and welfare. The decision, known as the endangerment finding, was based on years of evidence, and it has underpinned EPA actions on climate change ever since.

The Trump administration is now tearing up that finding as it tries to roll back climate regulations on everything from vehicles to industries.

“This is a big deal,” EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin said in announcing with President Donald Trump on Feb. 12, 2026, that the administration had “terminated” the endangerment finding. Zeldin argued that the finding had “no basis in law.” Trump, smiling next to him, talked about the benefits of fossil fuels and said the finding that greenhouse gas emissions endanger public health and welfare “had no basis in fact. None whatsoever.”

There’s no question that the EPA’s decision will be challenged in court. The legal question over the EPA’s authority to regulate greenhouse gases will be debated, just as it was in 2009. The administration’s claim that the finding was scientifically wrong, however, has no basis in fact.

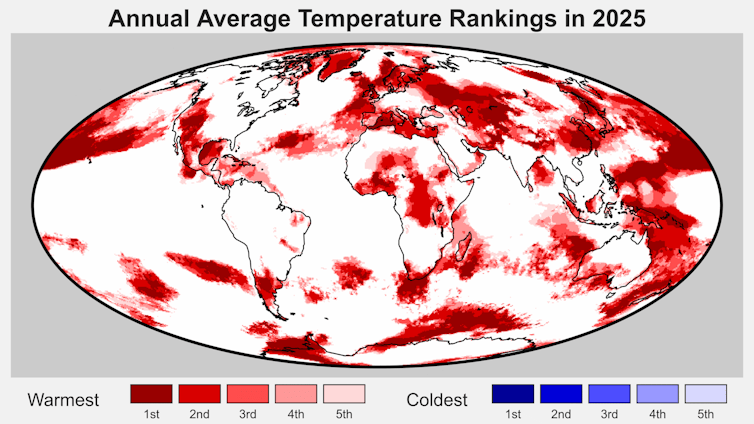

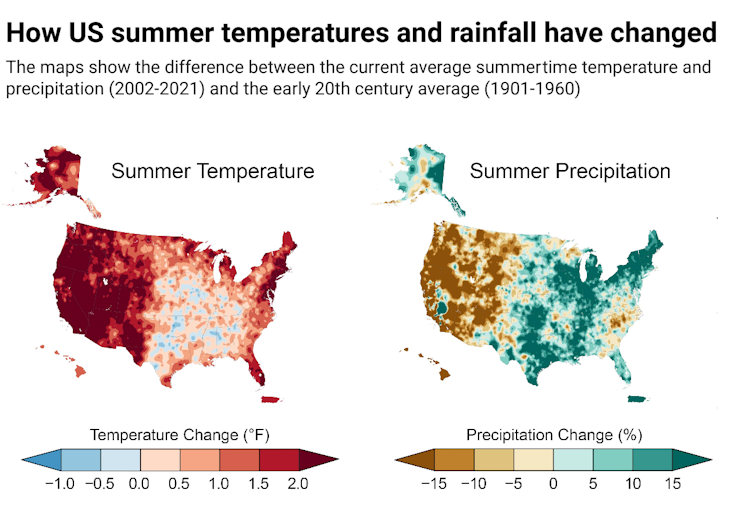

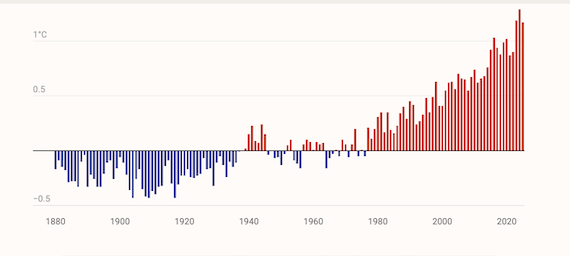

The world just experienced its three hottest years on record, evidence of worsening climate change is stronger now than ever before, and people across the U.S. are increasingly experiencing the harm firsthand.

Several legal issues have already surfaced that could get in the EPA’s way. They include evidence from emails submitted in a court case that suggest political appointees sought to direct the scientific review that the administration has used to defend its plan, at the exclusion of respected scientific sources. On Jan. 30 a federal judge ruled that the Department of Energy violated the law when it handpicked five researchers to write the climate science review. The ruling doesn’t necessarily stop the EPA, but it raises questions.

To understand what happens now, it helps to look back at history for some context.

The Supreme Court started it

The endangerment finding stemmed from a 2007 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Massachusetts v. EPA.

The court found that various greenhouse gases, including carbon dioxide, were “pollutants covered by the Clean Air Act,” and it gave the EPA an explicit set of instructions.

The court wrote that the “EPA must determine whether or not emissions from new motor vehicles cause or contribute to air pollution which may reasonably be anticipated to endanger public health or welfare.”

But the Supreme Court did not order the EPA to regulate greenhouse gas emissions. Only if the EPA found that emissions were harmful would the agency be required, by law, “to establish national ambient air quality standards for certain common and widespread pollutants based on the latest science” – meaning greenhouse gases.

The EPA was required to follow formal procedures – including reviewing the scientific research, assessing the risks and taking public comment – and then determine whether the observed and projected harms were sufficient to justify publishing an “endangerment finding.”

That process took two years. EPA Administrator Lisa Jackson announced on Dec. 7, 2009, that the then-current and projected concentrations of six key greenhouse gases in the atmosphere – carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, hydrofluorocarbons, perfluorocarbons and sulfur hexafluoride – threatened the public health and welfare of current and future generations.

Challenges to the finding erupted immediately.

Jackson denied 10 petitions received in 2009-2010 that called on the administration to reconsider the finding.

On June 26, 2012, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit upheld the endangerment finding and regulations that the EPA had issued under the Clean Air Act for passenger vehicles and permitting procedures for stationary sources, such as power plants.

This latest challenge is different.

It came directly from the Trump administration without going through normal channels. It was, though, entirely consistent with both the conservative Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025 plan for the Trump administration and President Donald Trump’s dismissive perspective on climate risk.

Trump’s burden of proof

To legally reverse the 2009 finding, the agency was required to go through the same evaluation process as before. According to conditions outlined in the Clean Air Act, the reversal of the 2009 finding must be justified by a thorough and complete review of the current science and not just be political posturing.

That’s a tough task.

Energy Secretary Chris Wright has talked publicly about how he handpicked the five researchers who wrote the scientific research review. A judge has now found that the effort violated the 1972 Federal Advisory Committee Act, which requires that agency-chosen panels providing policy advice to the government conduct their work in public.

All five members of the committee had been outspoken critics of mainstream climate science. Their report, released in summer 2025, was widely criticized for inaccuracies in what they referenced and its failure to represent the current science.

Scientific research available today clearly shows that greenhouse gas emissions harm public health and welfare. Importantly, evidence collected since 2009 is even stronger now than it was when the first endangerment finding was written, approved and implemented.

Berkeley Earth, CC BY-NC

For example, both a 2025 review by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine and a 2019 peer-reviewed assessment of the evidence related to greenhouse gas emissions’ role in climate change determined that the evidence supporting the endangerment finding became even stronger in the years after 2009.

The Sixth Assessment of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, a report produced by hundreds of scientists from around the world, found in 2023 that “adverse impacts of human-caused climate change will continue to intensify.”

Fifth National Climate Assessment

In other words, greenhouse gas emissions were causing harm in 2009, and the harm is worse now and will be even worse in the future without steps to reduce emissions.

In public comments on the Department of Energy’s problematic 2025 review, a group of climate experts from around the world reached the same conclusion, adding that the Department of Energy’s Climate Working Group review “fails to adequately represent this reality.”

What happens now that the EPA has dropped the endangerment finding

As an economist who has studied the effects of climate change for over 40 years, I am concerned that the EPA’s rescinding the endangerment finding will lead to faster efforts to roll back U.S. climate regulations meant to slow climate change.

It will also give the administration cover for further actions that would defund more science programs, stop the collection of valuable data, freeze hiring and discourage a generation of emerging science talent.

Cases typically take years to wind through the courts, but both the Environmental Defense Fund and the Union of Concerned Scientists expect to file lawsuits quickly once the rescission is published in the Federal Register.

Unless a judge issues an injunction, I expect to see an accelerating retreat from U.S. efforts to reduce climate change. For example, consider the removal in early February of the climate science chapter from a new “Reference Manual on Scientific Evidence” that advises judges. Republican state attorneys general had complained to the Federal Judicial Center of the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine that the manual “treated human influence on climate as fact.” But it is fact. That is not just my opinion. The National Academies itself said so in 2020 and again in 2025.

I see no scenario in which a legal challenge doesn’t end up before the Supreme Court. I would hope that both the enormous amount of scientific evidence and the words in the preamble of the U.S. Constitution would have some significant sway in the court’s considerations. It starts, “We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union,” and includes in its list of principles, “promote the general Welfare.

This article, originally published Feb. 2, 2026, has been updated with EPA rescinding the endangerment finding.![]()

Gary W. Yohe, Professor of Economics and Environmental Studies, Wesleyan University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

© 2026 All Rights Reserved

© 2026 All Rights Reserved