( Middle East Monitor ) – It is rare for an Israeli voice to emerge from the heart of crisis and articulate what politics itself cannot.

Yet Yuval Noah Harari—neither a politician nor an agent of state power, but a globally respected social thinker—has done precisely that. He argues that the Israeli–Palestinian conflict is no longer a dispute over land, but over the moral certainties each side wraps around its own absolute narrative.

In a substantial essay published recently in the Financial Times, Harari does not position himself as a champion of the Palestinian story. He does something more unsettling: he dismantles the Israeli narrative from within, stripping it of the historical sanctity long used to justify force.

He states plainly that the land between the river and the sea is not too small to accommodate both peoples, and that what obstructs coexistence is not geography but myth.

In a rare departure from mainstream Israeli discourse, he acknowledges that Palestinians are not latecomers to the land, and that they possess a full and legitimate right to live on it—not as guests, nor as “potential inhabitants,” but as children of the place, as rooted as Jews and perhaps more deeply woven into its daily life.

This raises an unavoidable question: can a voice like Harari’s—however morally grounded—find an audience within Israel’s political and military establishment?

Can a discourse that challenges historical certainties and affirms Palestinian rights gain traction in a society built on fear and the centrality of force?

Or will his intervention remain suspended in the air, with no political ground on which to land?

Harari proceeds to unravel the Israeli narrative to its logical ends.

He reminds readers that after most Jews left the land, they were never barred from returning. Neither Romans nor Arabs nor Ottomans closed the gates.

The uncomfortable truth, he argues, is that Jews did not wish to return, and that the land now framed as an “eternal dream” was, for centuries, a destination for only a very small minority.

He then punctures another foundational myth: prayer, however sincere, does not constitute a deed of ownership.

His analogy is sharp: if one prays daily for a neighbour’s house to become one’s own, after how many prayers may one claim it at the land registry?

With this, Harari dismantles the emotional core of Zionist reasoning—the idea that religious longing can be converted into political entitlement.

He also situates Palestinians in their historical reality.

When the first Zionists arrived in the late nineteenth century, the land was far from empty.

It was alive with cities—Acre, Jaffa, Gaza, Nablus, Hebron—and with hundreds of villages forming a deep social and cultural fabric.

And even if Palestinian national identity was not fully crystallised at the time, that does not negate its existence today.

Nations are not born in a single moment; they take shape over time. Two centuries of shared experience are more than enough for a nation to come of age.

Harari also critiques the Palestinian narrative, though from a different angle.

He does not deny Palestinian existence or their right to the land. Instead, he challenges the idea of a singular “first origin”—a notion he sees as illusory on both sides.

The land between the river and the sea has never belonged exclusively to one people. Its history is a palimpsest of conquests, migrations and overlapping identities.

“Palestine” itself was historically an administrative designation, its borders shifting with empires. The British, not earlier rulers, drew the contours of Mandatory Palestine as we know it today.

Yet Harari avoids the trap of false equivalence.

He does not use these facts to undermine Palestinian legitimacy.

Rather, he argues that nations derive their legitimacy not from ancient names or imperial maps, but from shared life, accumulated memory and the daily intimacy between people and their land.

In the final part of his essay, Harari attempts to balance the intertwined truths.

He notes that describing Israelis as “European colonisers” ignores a Jewish presence that has existed in the land for millennia, and overlooks the fact that half of today’s Israeli Jews are from the Middle East—from Baghdad, Cairo, Sana’a, Aleppo, Tripoli, Tunis, Rabat.

But even as he offers this clarification, Harari does not grant Jews an absolute right.

He places them in their proper historical context: an ancient presence, yes, but not an eternal privilege, nor a political title deed for the twentieth century.

He returns to the essential point: Palestinians in the 1920s were the actual inhabitants of the land, and Jewish persecution in Europe was not their responsibility.

No people can be asked to bear the burden of crimes committed elsewhere.

But time, Harari insists, has transformed the landscape. A century later, the land is home to two peoples of equal number, equal wound, and equal lack of alternatives.

Seven million Jews with nowhere else to go, and seven million Palestinians with no other homeland. This fact alone undermines every absolute claim and every narrative that seeks to erase the other.

From here, Harari reaches his central argument: peace cannot be built on temporary arrangements or maps drawn under duress.

It requires generosity—a concept that sounds almost naïve in an age of weapons, yet is the only force capable of breaking the cycle of fear.

He urges Israelis to stop clinging to every hill and spring. Land is not the ultimate prize; the neighbour behind the wall is.

Israel’s true interest lies not in expanding its borders but in ensuring that Palestine becomes a real state—secure, prosperous, capable of being a neighbour rather than a captive.

He calls on Palestinians to offer a different kind of generosity: legitimacy.

A recognition that could open the door to broader Arab and Muslim acceptance, granting Israelis a sense of security—ironically, the very sense Palestinians themselves have been denied for decades.

In the end, Harari warns that time is not infinite.

Those who speak of “eternity” forget that eternity is an illusion, and that the world is changing at a pace that threatens everyone—from next‑generation nuclear weapons to autonomous AI armies.

The alternative to “two states for two peoples” may not be one state, but zero states for zero people, if stubbornness continues to strangle the future.

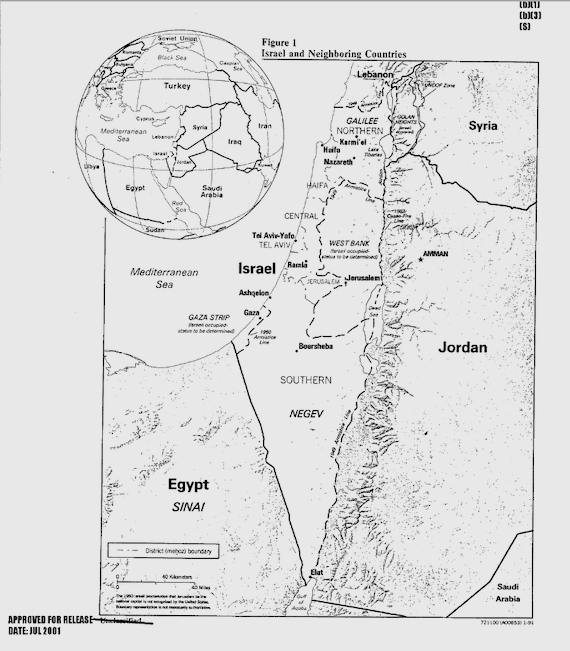

US CIA Map of Israel and its Neighbors, 2001. Public Domain.

With this intervention, Harari steps beyond competing narratives to articulate something simple and profound: that land is not redeemed by myth, nor liberated by force, but by human beings who recognise one another, who relinquish their lethal certainties, and who choose to be neighbours rather than enemies.

Yet the question remains: Can Israel, with a political and military structure steeped in the arrogance of power, listen to such a voice?

Can a discourse that affirms Palestinians’ full right to dignified life, and calls for a real Palestinian state, find space in a society built on fear and the primacy of force?

Or will Harari’s voice remain, like many before it, a cry in a valley that hears nothing but its own echo?

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Monitor or Informed Comment.

Unless otherwise stated in the article above, this work by Middle East Monitor is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Unless otherwise stated in the article above, this work by Middle East Monitor is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

© 2026 All Rights Reserved

© 2026 All Rights Reserved