No. 38 in the first edition of Edward FitzGerald’s translation of the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám suggests that although we are in motion as long as we live, it is just for “one moment” and our caravan of life has as its destination a grim and final death — nothingness. This stanza is another that denies the reality of the afterlife and, moreover, questions the meaningfulness of life itself.

XXXVIII.

One Moment in Annihilation’s Waste,

One Moment, of the Well of Life to taste —

The Stars are setting and the Caravan

Starts for the Dawn of Nothing — Oh, make haste!

The original is no. 60 in the Bodleian manuscript, which is also on the internet here.

این قافلهٔ عمر عجب میگذرد

دریاب دمی که با طرب میگذرد

ساقی غم فردای حریفان چه خوری

پیش آر پیاله را که شب میگذرد

A. J. Arberry translated the first two lines this way:

This caravan of life is passing amazingly:

seize the moment that is passing with joy.

In my translation of the Bodleian manuscript, I gave the last two lines in contemporary free verse this way:

Barkeep, why grieve about the future fate of friends?

Bring out your finest vintage — since the night is disappearing.

—-

Order Juan Cole’s contemporary poetic translation of the Rubáiyát from

or Barnes and Noble.

or for $16 at Amazon Kindle

——-

FitzGerald stayed relatively close to the original, though he did not make the switch from the image of the trade convoy in the first line to that of the barroom scene in the last two, preferring to stay with the metaphor of the caravan.

Some Omarian themes were anticipated by earlier Persian poets, for instance, by Abu Nazar `Asjadi (d. around 1042), active at the court of the Ghaznavid emperors Mahmud and Mas`ud in what is now Afghanistan. Ghazni, the capital, is ninety miles southwest of Kabul. `Asjadi is probably a contemporary of the Western poet who sang The Song of Roland. This poem is attributed to him:

صبح است و صبا مشکفشان میگذرد

دریاب که از کوی فلان میگذرد

برخیز چه خسبی که جهان میگذرد

بویی بستان که کاروان میگذرد

It goes like this in blank verse English translation

It’s morning and the breeze wafts its fragrance

Breathe in deep, since it passes by her lane.

Get up, why sleep, when the world’s passing by?

Inhale her scent, the caravan departs.

Here the caravan does not symbolize a fleeting life bereft of meaning but rather a momentary opportunity to find a beloved. He or she lives in a lane in the capital of Ghazni. Because of gender segregation, the lover can only sense her presence indirectly — he breathes in the same breeze as she does, which carries her perfume. The lover is castigated for sleeping in, and missing the opportunity to court her. Here it is the opportunity for love that is the caravan, and it is not waiting around.

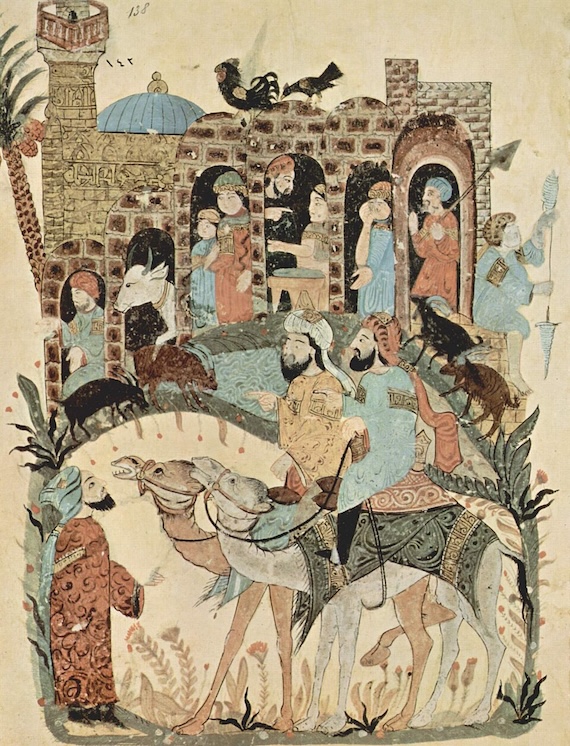

Caravan, by Yahya ibn Mahmud al-Wasiti, 13th c., from the Maqamat of al-Hariri. Public Domain. Via Wikimedia Commons .

To `Asjadi is attributed a poem that seems to anticipate themes later found in the Khayyam corpus as assembled by Mahmud Yerbudaki in Shiraz in 1460. A famous one, noted by the great Persian scholar Edward Granville Browne, is this:

از شرب مدام و لاف مشرب توبه

وز عشق بتان سیم غبغب توبه

دل در هوس شراب و بر لب توبه

زین توبهٔ نادرست یارب توبه

Here is my blank verse interpretation:

I rue that I drink wine and boast of it,

and fall for idols with a silver face–

and that my heart and lip yearn for a drink.

Then, of this false contrition I repent.

The trope of repenting a past repentance in favor of earthy pastimes, in a sardonic evocation of pious themes for libertine purposes, is characteristic of the later Omarian poems.

For more commentaries on FitzGerald’s translations of the Rubáiyát, see

FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám: Commentary by Juan Cole with Original Persian

© 2026 All Rights Reserved

© 2026 All Rights Reserved