Quatrain no. 22 in the first edition of Edward FitzGerald’s translation of The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám again invokes the image of the way the living are walking atop those who lived and died before them, leaving them alone in the “room” of the world. The departed dead are dressed in blooms, i.e. flowers grow from their graves. These images are drawn from the Khayyami poetry,

XXII.

And we, that now make merry in the Room

They left, and Summer dresses in new Bloom,

Ourselves must we beneath the Couch of Earth

Descend, ourselves to make a Couch — for whom?

Arberry (Romance 205-206) identified the source of the first two lines as no. 404 in the Calcutta manuscript, which is also found here with one word being different:

برخیز و مخور غم جهان گذران

بنشین وجهان به شادمانی گذران

در طبع جهان اگر وفایی بودی

نوبت به تو خود نیامدی از دگران

I would translate this in blank verse this way:

Get up, do not grieve for this fleeting world.

Sit down, and let it pass you by in joy.

For if the world were marked by faithfulness,

the dead would not have given you your turn.

Arberry asserted that the second two lines came from the last two lines of no. 85 in the Calcutta manuscript, which is also found here .

ابر آمد و باز بر سر سبزه گریست

بی بادهٔ گلرنگ نمیباید زیست

این سبزه که امروز تماشاگه ماست

تا سبزهٔ خاک ما تماشاگه کیست!

I render it this way:

The cloud shed tears once more upon the grass;

No one should live without a fine rosé.

this lawn that now delights our eyes — when it

grows from our dust whom will it entertain?

—-

Order Juan Cole’s contemporary poetic translation of the Rubáiyát from

or Barnes and Noble.

or for $16 at Amazon Kindle

——-

The lugubrious theme of our living above a layer of the deceased is found throughout classical Persian poetry. It is worth remarking that it is a Muslim theme, since Muslims practice burial, whereas in old Iran Zoroastrians exposed the bodies of the dead in towers so that birds would pick them clean. Zoroastrians believe the earth is sacred and did not want to pollute it by burying corpses in it. Likewise, Hindus, who neighbored the Iran-based empires and lived there as long-distance merchants, cremated their dead and spread the dust in a river.

Saadi of Shiraz (d. 1291) says in poetry entitled “Counsels” (Mava`iz),

بسیار سالها به سر خاک ما رود

کاین آب چشمه آید و باد صبا رود

این پنج روزه مهلت ایام، آدمی

بر خاک دیگران به تکبر چرا رود؟

ای دوست بر جنازهٔ دشمن چو بگذری

شادی مکن که با تو همین ماجرا رود

which I translate literally this way:

For many years this stream from a spring will flow over our dust;

and as the water goes, the morning breeze comes.

During this brief respite of life, which seems no more than five days,

why stride arrogantly over the dust of others?

Friend, when you pass by the funeral of an enemy

do not rejoice, since the same procedure will be applied to you.

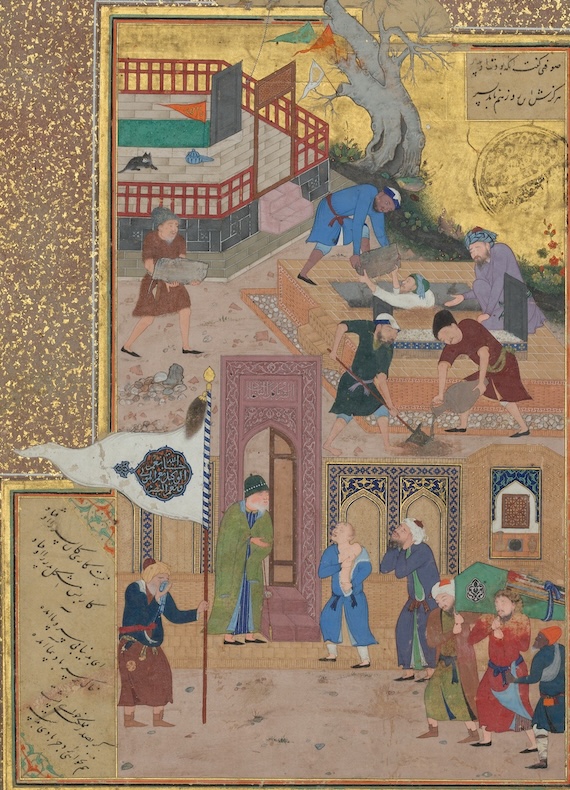

“Funeral Procession”, Folio 35r from a Farid al-Din Attar’s Language of the Birds (Mantiq al-Tayr), Calligrapher Sultan ‘Ali al-Mashhadi Iranian, dated 892 AH/1486 CE, Herat. This illustration is associated with a story related by the hoopoe as a response to a bird who complains about his fear of death. In the story, a son grieves the death of his father in front of his coffin and a sufi soothes him, explaining that his father had experienced much pain and that no one can avoid death. Here, the painter depicts the incident as occurring in front of a cemetery gate. The scene behind the gate is replete with motifs that are irrelevant to the story itself. The viewer at the court may have enjoyed deciphering them. Public Domain. Via Met Museum.

Vinnie-Marie D’Ambrosio suggested that this quatrain of Khayyam in FitzGerald’s translation may have inspired T. S. Eliot’s line, “In the room the women come and go / Talking of Michelangelo” in “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock. Michaelangelo is the symbol of art that lives beyond its age. She showed that the Rubaiyat echoes in much of Eliot’s poetry.

—-

For more commentaries on FitzGerald’s translations of the Rubáiyát, see

FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám: Commentary by Juan Cole with Original Persian

© 2026 All Rights Reserved

© 2026 All Rights Reserved