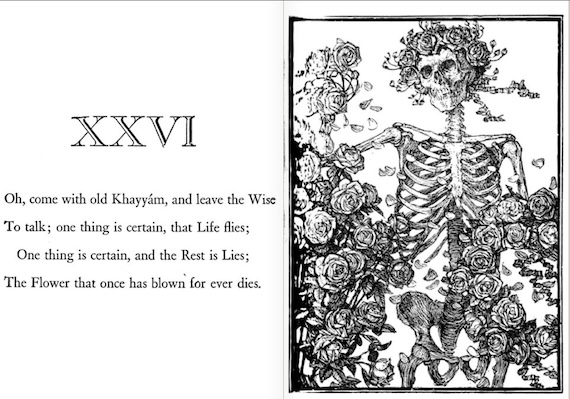

Stanza no. 26 in the first edition of Edward FitzGerald’s translation of The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám calls the notion of an afterlife a “lie” and compares the death of an individual to the demise of a flower such as an individual tulip. Actually I think it is saying that human beings are not like perennials such as tulips, which return every year. They don’t. And, of course, not all tulips return, either.

XXVI.

Oh, come with old Khayyam, and leave the Wise

To talk; one thing is certain, that Life flies;

One thing is certain, and the Rest is Lies;

The Flower that once has blown for ever dies.

A. J. Arberry said that FitzGerald here was working from the last two lines of no. 35 in the Bodleian manuscript, which is on the web here.

مِی خور که به زیرِ گِل بسی خواهی خفت

بیمونس و بیرفیق و بیهمدم و جفت

زنهار! به کس مگو تو این رازِ نهفت

هر لاله که پَژْمُرد، نخواهد بِشْکفت

I translated the last two lines as no. 34 in my The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám: A New Translation from the Persian in free verse:

- “Be careful to tell no one this hidden secret:

that not every withered lily will bloom again.”

—-

Order Juan Cole’s contemporary poetic translation of the Rubáiyát from

or Barnes and Noble.

or for $16 at Amazon Kindle

——-

The Rubáiyát‘s theme that death is permanent influenced modernist poets such as T. S. Eliot in his youth and before his turn to the Church. It can be seen in his The Wasteland (via The Poetry Foundation. “That corpse you planted last year in your garden, has it begun to sprout? Will it bloom this year?” he wrote. This is also a reference to FitzGerald’s 1:15, “As, buried once, Men want dug up again”, which I discussed earlier . See Vinnie-Marie D’Ambrosio, Eliot Possessed: T. S. Eliot and FitzGerald’s Rubaiyat (New York: New York University Press, 1989), 183.

Eliot wrote,

- “Unreal City,

Under the brown fog of a winter dawn,

A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many,

I had not thought death had undone so many.

Sighs, short and infrequent, were exhaled,

And each man fixed his eyes before his feet.

Flowed up the hill and down King William Street,

To where Saint Mary Woolnoth kept the hours

With a dead sound on the final stroke of nine.

There I saw one I knew, and stopped him, crying: ‘Stetson!

‘You who were with me in the ships at Mylae!

‘That corpse you planted last year in your garden,

‘Has it begun to sprout? Will it bloom this year?

‘Or has the sudden frost disturbed its bed?

‘Oh keep the Dog far hence, that’s friend to men,

‘Or with his nails he’ll dig it up again!”

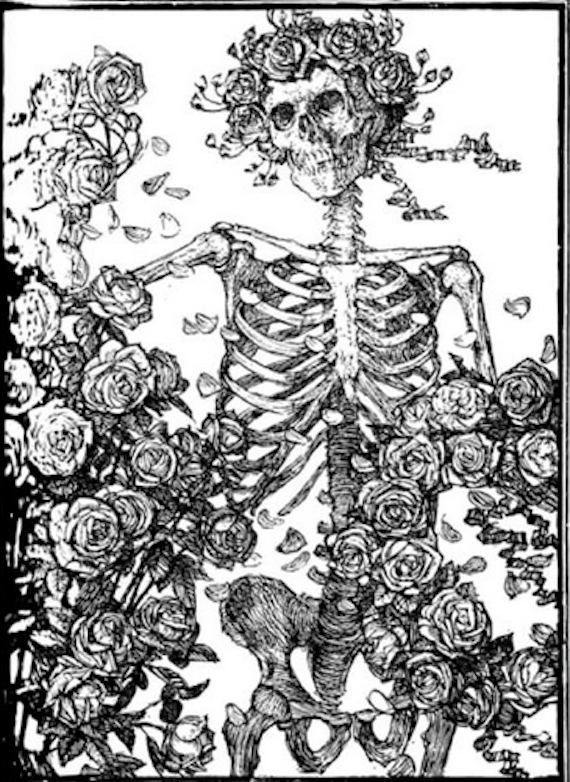

The cultural influence of this poem also extended into later 20th century popular culture. Edmund J. Sullivan was a newspaper and book illustrator who used rococo and grotesque images and was influenced by Art Nouveau’s appeal to organic forms. He did black and white drawings for an edition of The Rubáiyát published in London by Methuen in 1913. This is how he illustrated this verse:

Fans of rock music may recognize it since it was used by Stanley Mouse and Alton Kelley for a Grateful Dead poster in 1966, and for the cover of the group’s second live album in 1971.

Although I understand that Jerry Garcia said that the origin of the name of the band, “The Grateful Dead,” derived from a dictionary, I have long wondered whether it wasn’t also indirectly inspired by the ambience of The Rubáiyát. The poem was enormously important for the 1950s Beats and the Sixties counter-culture, and was frequently referred to by Jack Kerouac, influential author of On the Road about youth rebellion against conventionality. Some of the Grateful Dead’s lyrics may also have been influenced by the Persian poem.

—-

For more commentaries on FitzGerald’s translations of the Rubáiyát, see

FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám: Commentary by Juan Cole with Original Persian

© 2026 All Rights Reserved

© 2026 All Rights Reserved