By Morteza Hajizadeh, University of Auckland, Waipapa Taumata Rau

(The Conversation) – For centuries, literature from Islamic regions, especially Iran, celebrated male homoerotic love as a symbol of beauty, mysticism and spiritual longing. These attitudes were particularly pronounced during the Islamic Golden Age, from the mid-8th to mid-13th centuries.

But this literary tradition gradually disappeared in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, under the influence of Western values and colonisation.

Islamic law and poetic licence

Attitudes towards homosexuality in early Islamic societies were complex. From a theological perspective, homosexuality started to become frowned upon from the 7th century, when the Quran was said to have been revealed to the Islamic Prophet Mohammad.

However, varying religious attitudes and interpretations allowed for discretion. Upper-class medieval Islamic societies often accepted or tolerated homosexual relationships. Classical literature from Egypt, Turkey, Iran and Syria suggests any prohibition of homosexuality was often treated with leniency.

Even in cases where Islamic law condemned homosexuality, jurists permitted poetic expressions of male–male love, emphasising the fictional nature of verse. Composing homoerotic poetry allowed the literary imagination to flourish within moral boundaries.

The classic Arabic, Turkish and Persian literature of the time featured homoerotic poetry portraying sensual love between males. This tradition was sustained by poets such as the Arab Abu Nuwas, the Persian masters Saadi, Hafiz and Rumi, and the Turkish poets Bâkî and Nedîm – all celebrating the beauty and allure of male beloveds.

In Persian poetry, masculine pronouns could be used to describe both male and female beloveds. This linguistic ambiguity that further legitimised literary homoeroticism.

A form of mystical desire

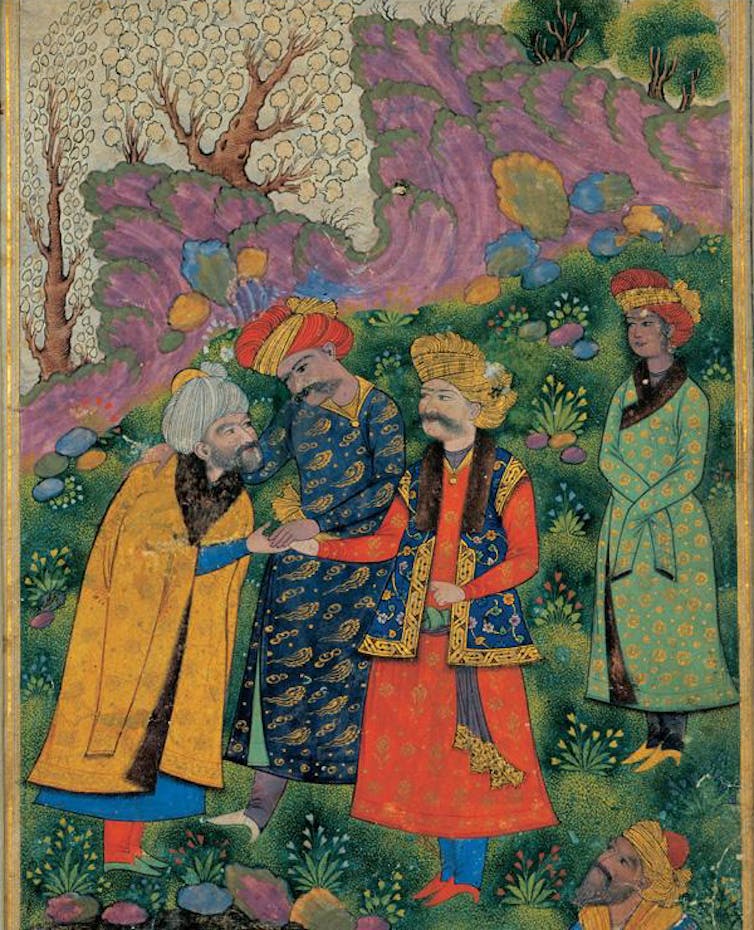

In Sufism – a form of mystical Islamic belief and practice that emerged during the Islamic Golden Age – themes of male–male love were often used as a symbol of spiritual transformation. As professor of history and religious studies Shahzad Bashir shows, Sufi narratives frame the male body as the primary conduit of divine beauty.

Religious authority in Sufism is transmitted through physical closeness between a spiritual guide, or sheikh (Pir Murshid), and his disciple (Murid).

The sheikh/disciple relationship enacted the lover–beloved paradigm fundamental to Sufi pedagogy, wherein disciples approached their guides with the same longing, surrender and ecstatic vulnerability found in Persian love poetry.

Literature suggests Sufi communities developed around a form of homoerotic affection, using beauty and desire as metaphors for accessing the hidden reality.

Thus, the saintly master became a mirror of divine radiance, and the disciple’s yearning signified the soul’s ascent. In this framework, embodied male love became a vehicle for spiritual annihilation and rebirth within the Sufi path.

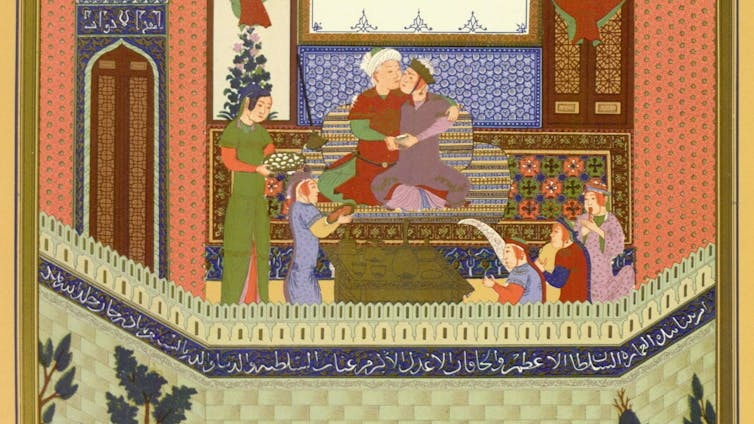

The legendary love between Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni and his male slave Ayaz exemplifies this. Overwhelmed by seeing the beauty of a naked Ayaz in a bath, Sultan Mahmud confesses:

When I saw only your face, I knew nothing of your limbs. Now I see them all, and my soul burns with a hundred fires. I do not know which limb to love more.

In other stories, Ayaz willingly offers himself to die at Mahmud’s hands. This symbolises spiritual transformation through the annihilation of the ego.

Wikimedia

The relationship between Rumi and Shams Tabrizi, both 13th-century Persian Sufis, is another example of male–male mystical love.

In one account from their disciples, the pair reunited after a long period of spiritual transformation, embraced each other, and then fell at each other’s feet.

Rumi’s poetry blurs spiritual devotion and erotic attraction, while Shams challenges the idea of idealised purity:

Why look at the reflection of the moon in a bowl of water, when you can look at the thing itself in the sky?

Homoerotic themes were so common in classical Persian poetry that Iranian critics claimed

Persian lyrical literature is essentially a homosexual literature.

The rise of Western values

By the late 19th century, writing poetry about male beauty and desire became taboo, not so much on religious injunctions, but because of Western influences.

British and French colonial powers imported a Victorian morality, heteronormativity and anti-sodomy laws to countries such as Iran, Turkey and Egypt. Under their influence, homoerotic traditions in Persian literature were stigmatised.

Colonialism amplified this shift, framing homoeroticism as “unnatural”. This was further reinforced by the strict administration of Islamic laws, as well as nationalist and moralist agendas.

Influential publications such as Molla Nasreddin (published from 1906 to 1933) introduced Western norms and mocked same-sex desire, conflating it with paedophilia.

Library of Congress, CC BY-SA

Iranian nationalist modernisers spearheaded campaigns to purge homoerotic texts, framing them as relics of a “pre-modern” past. Even classical poets such as Saadi and Hafez were reframed or censored in Iranian literary histories from 1935 onward.

A millennium of poetic libertinism gave way to silence, and censorship erased male love from literary memory.![]()

Morteza Hajizadeh, Hajizadeh, University of Auckland, Waipapa Taumata Rau

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

© 2026 All Rights Reserved

© 2026 All Rights Reserved