Quatrain no. 35 in the first edition of Edward FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám is a meditation on death and the way that the dead live on in the artefacts of our daily lives. Their emotions were the same as ours, their loves and passions, now faded, were no less ardent than our own. They are now clay, and some of the clay objects, like jugs and cups, in our daily lives, are really just survivals of those people of the past. It is a grim vision:

XXXV.

I think the Vessel, that with fugitive

Articulation answer’d, once did live,

And merry-make; and the cold Lip I kiss’d

How many Kisses might it take — and give!

This stanza is drawn from no. 9 in the Bodleian manuscript, which is the same as no. 50 in the Calcutta manuscript. It is on the internet now here.

این کوزه چو من عاشقِ زاری بودهست

در بندِ سرِ زلفِ نگاری بودهست

این دسته که بر گردنِ او میبینی

دستیست که بر گردنِ یاری بودهست

It is about a clay wine cup that is made from the clay of someone’s dead beloved. This trope of human beings turning into clay on their deaths and then that clay being made into wine cups is common in Arabic and Persian poetry.

I translated it in free verse in my own book on the Rubaiyat (no. 8). Literally it goes like this:

This wine jug was once, like me, a miserable lover —

captive to the tresses of a heartthrob.

Its handle, which you see on its neck,

was once an arm around the neck of a sweetheart.

—-

Order Juan Cole’s contemporary poetic translation of the Rubáiyát from

or Barnes and Noble.

or for $16 at Amazon Kindle

——-

A similar notion shows up in the Arabic quatrains of the renowned freethinking poet Abu al-Ala al-Ma’arri (d. 1057), from Ma`arrat al-Nu`man near Aleppo in what is today Syria. Members of the fundamentalist group from which the current (2026) government of Syria is drawn demolished his statue during the Syrian civil war. Compare al-Ma`arri:

صَاحِ هَذِهْ قُبُورُنَا تَمْلَأُ الرُّحْبَ فَأَيْنَ الْقُبُورُ مِنْ عَهْدِ عَادِ؟

خَفِّفِ الْوَطْءَ مَا أَظُنُّ أَدِيمَ الأَرْضِ إِلَّا مِنْ هَذِهِ الْأَجْسَادِ

Friend, these are our graves, filling a wide expanse;

So where are the tombs from the era of `Ad?

Tread lightly, for I fear the surface of the earth

consists of naught but these corpses.

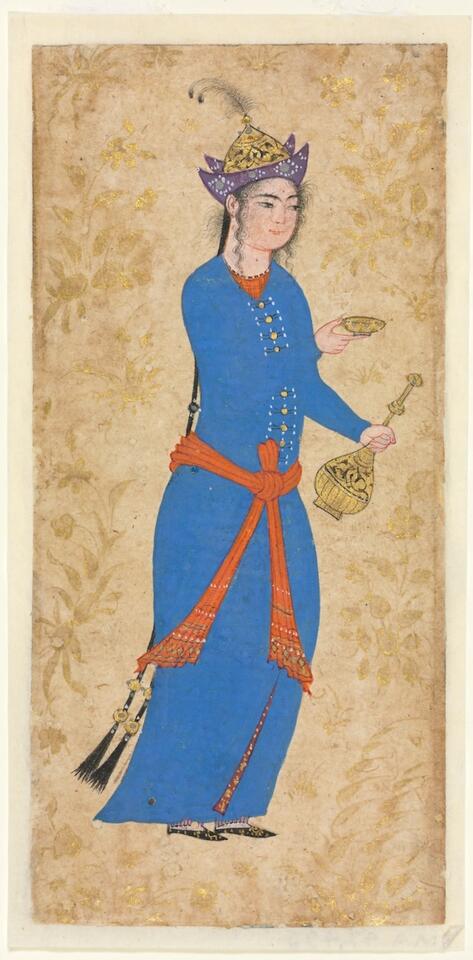

“Princess with Wine Bottle and Cup,” c. 1550–1600 Iran, Qazvin or Isfahan, Safavid period (1501-1722). Cleveland Museum of Art

There is also something of Edgar Allan Poe in this mingling of images of love and death, as with his verse about a dead beloved, Annabel Lee:

For the moon never beams, without bringing me dreams

Of the beautiful Annabel Lee;

And the stars never rise, but I feel the bright eyes

Of the beautiful Annabel Lee;

And so, all the night-tide, I lie down by the side

Of my darling—my darling—my life and my bride,

In her sepulchre there by the sea—

In her tomb by the sounding sea.

This theme of necrophilia is complicated in no. 35 of the Rubáiyát, though, since the departed beloved is present in a wine jug that still dispenses a fine vintage.

For the previous quatrain, see “Once dead you never shall return:” FitzGerald’s The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám 1:34.

For more commentaries on FitzGerald’s translations of the Rubáiyát, see

FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám: Commentary by Juan Cole with Original Persian

© 2026 All Rights Reserved

© 2026 All Rights Reserved