Quatrain no. 28 in the first edition of Edward FitzGerald’s The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám continues riffing on stanza 121 in the Bodleian manuscript.

XXVIII.

With them the Seed of Wisdom did I sow,

And with my own hand labour’d it to grow :

And this was all the Harvest that I reap’d-

“I came like Water, and like Wind I go.”

یک چند به کودکی به استاد شدیم

یک چند به استادی خود شاد شدیم

پایان سخن نگر که ما را چه رسید

چون آب در آمدیم و بر باد شدیم

I translated this one in my book in blank verse, but here it is as an alexandrine in abcb:

Once in our childhood we learned under a master,

then for a while we each were thought a wunderkind.

Now look at what became of us– the story’s end:

Like water we came in, and went out like the wind.

FitzGerald caught the gist of the original, which questions the ultimate worth of learning, for even the greatest scholars or master craftsmen ultimately experience death.

The phrase FitzGerald gave as “like the wind I go” and I am giving as “went out like the wind” can also mean “came to ruin” (bar bād).

—-

Order Juan Cole’s contemporary poetic translation of the Rubáiyát from

or Barnes and Noble.

or for $16 at Amazon Kindle

——-

We can compare these sentiments to lines in a ghazal by the Seljuk court poet Anvari (fl. 1100s AD):

خانهٔ صبر دلم کز غم تو گشت خراب

زان لب لعل شکربار خود آباد کنی

خاک پای توام و زاتش سودای مرا

برزنی آب و همه انده بر باد کنی

I would translate it this way:

You left my heart’s abode of patience in ruins

But then your candy, ruby lips built it again.

I am the dust at your feet, and by my love’s fire

You douse this flame and scatter sorrow to the wind.

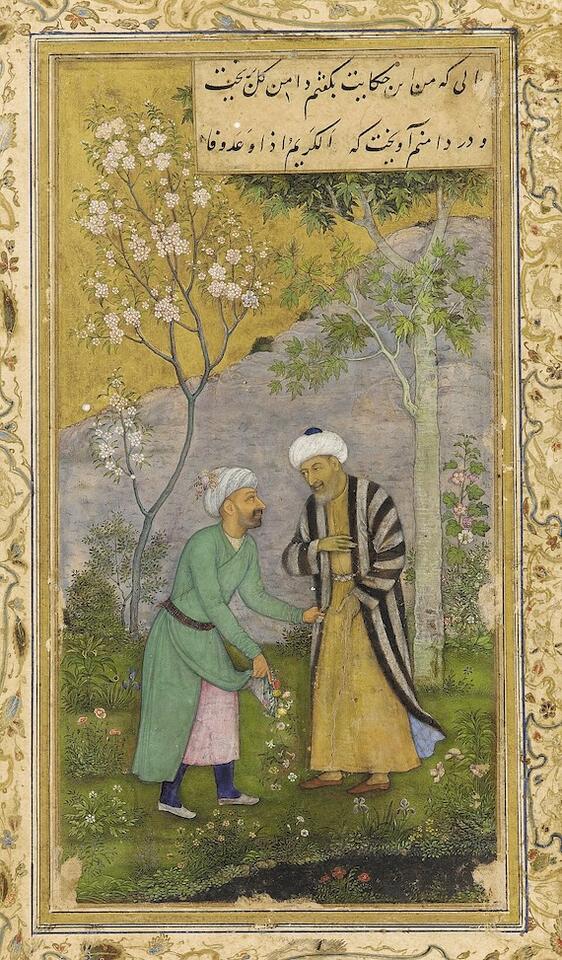

Attributed to Govardhan, “Sa’di in a Rose garden,” from a manuscript of the Gulistan (Rose garden) by Sa’di. [Sa`di’s works were used to teach young people basic values and literacy.] Freer Gallery. Public Domain. Via Wikimedia Commons.

Or here is the opening of a ghazal by Hafez of Shiraz (d. 1390) that plays with the various meanings of bar bād

زُلف بَر باد مَده تا نَدَهی بَر بادَم

ناز بُنیاد مَکُن تا نَکَنی بُنیادَم

مِی مَخور با هَمه کَس تا نَخورَم خونِ جِگَر

سَر مَکِش تا نَکِشَد سَر به فَلَک فَریادَم

Here is a prose translation (the only way I could show all the wordplay):

Don’t let the breeze blow through your hair, casting me to the wind.

Don’t lay the groundwork for flirting, crushing my foundation.

Do not drink wine with just anyone, lest it break my heart.

Do not lift up your head in pride, lest my cry go up to heaven.

The Persian bād or wind is derived from proto-Indo-European *h₂wéh₁n̥ts, meaning wind or blowing. German and English kept the “w” and it became “wind.” In French the “w” became a “v,” giving vent; likewise Spanish viento.. It also became a “v” in Old Persian, in which vata means wind. “V” often becomes “b” (a lot of Mexicans, for instance, pronounce Vera Cruz as Bera Cruz). So in modern Persian “vata” became bād.

—-

For more commentaries on FitzGerald’s translations of the Rubáiyát, see

FitzGerald’s Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám: Commentary by Juan Cole with Original Persian

© 2026 All Rights Reserved

© 2026 All Rights Reserved